First, let me say that I did not choose the following question because of all the nice compliments in it – well, or not only because of that – but because it follows up nicely on what we were discussing last Thursday: the question of how one goes about making a functional artistic life.

Q.

It dawned on me, that since I've been writing about Art vs. Commercialism, I'd really like to hear your thoughts on this. I really do believe writers should follow their dreams, but both you and I know it's a miserable slog (not in your case, fortunately), to make a living at if you're only writing esoteric fiction for an (unfortunately) limited audience. I'm fearful, honestly, that a lot of the people in our "club" are going to strive and suffer for naught. Like I've said, you got lucky and hit the sweet spot where your fiction, which is certainly not Carver-style classic minimalism but more Phil Dick (although not all the time) was accepted and promoted; along with the fact that you're a soft-spoken, intelligent, and thoughtful presenter for your ideas. (In some ways, you're an odd match for your material - if I had met you and listened to you in person, I'd never guessed you wrote stuff like "Spiderhead." You simply don't match some of the more "colorful" characters I've met in genre.)

Anyway, I hope you'll consider the question. I think your answer, even if not the be-all and end-all last word on it, would be interesting.

A.

Well, it’s a statistical certainty that a lot of Club members are going to, as you put it, “strive and suffer for naught” – depending, of course, on how we define “naught.” Very few writers get published, fewer still publish well, fewer still get to make it their full-time job.

Even after all these years, and with all the good luck I’ve had, I’m still not at a place where fiction writing is my full-time job, exactly. It’s close, yes, and I’m very grateful for that, but I still teach and do visiting writer gigs and university visits and public readings and travel journalism on the side and now Story Club. There’s nothing to complain about there, not at all; just saying that, after all of my good luck, it’s still a bit of a hustle.

And I think this is true for most of the very well-published writers I know.

All of this is to say, I don’t think there ever comes a time where concerns about art vs. commerce aren’t hovering over a writer (any writer’s) head.

Let’s look at this supposed opposition a bit and see how we might work with it…

When, at the end of my long (long) apprenticeship, I finally began to understand writing as a form of earnest communication and entertainment…that’s when I started publishing. I mean, that was how I started publishing: by yielding to my natural desire to entertain, by accepting that being entertaining is not necessarily an “anti-art” stance and, on the contrary — for me, anyway, there was a fortunate dovetailing between “doing my best work” and “getting published.”

I want to say that I know this dovetailing is not true for everyone.1 But somehow, when I imagine that I’m writing for a magazine – in particular, since 1992, The New Yorker – this knowledge causes me to write my best. It’s as if whatever adjustments I make along these lines (to the pace of the text and the timing/scope of the beats and the flavor of the humor) are exactly those adjustments that bring forward my best artistic self.

In my early, unpublished, work, I was mostly writing to show off for my reader (and, in a sense, to “subdue” him/strike him with awe at all that I knew), rather than to engage him. So, the reader, correctly, felt these stories to be condescending. No one wanted to read them, even friends and family and….well, even I didn’t really want to read them.

But as soon as I started to say, “Let me delight the reader,” i.e., “Let me put this editor in a position where he would be thrilled to publish this,” my editing process started to become more natural. I knew what to do, basically. I’d been doing it all my life, out there in the “real” world, this attempting-to-engage.

Now, as I said above, yes, this “dovetailing” effect may be unique to me.

But I’d also like to suggest that…maybe it’s not.

For some of us, there may be no intersection between “what I want to write” and “what people want to read.” We may hate even thinking about it that way. But I have a feeling that, for most of us, our work would benefit from reaching out to others more, trusting more in our readers. I have seen, in many of my students, that the first proof of progress is that their stories become more cognizant of the existence of the reader – more fun, less unnecessarily dense, truer to life, fairer, warmer; they start engaging with issues that people are really worried about, they start showing emotional states that draw the reader in because they seem familiar, and so on. The language becomes less concerned with pyrotechnics and more with conveying something of mutual interest. There is less interest in concealment in the name of not being corny; more interest in giving the reader the simple facts she needs in order for the stakes to rise; the writer becomes committed to taking the reader on a wild-but-meaningful ride; I note a movement toward simplicity and real human feeling. And all of this, really, has to do with wanting to create a state of higher engagement with the reader.

I thought of it then, and still do, as “being willing to entertain.” Some hear this word with slightly crass connotations, and certainly much that is considered “entertaining” these days has little of the above qualities in it – but when I use that word, I’m thinking of certain literary readings I’ve attended, where the audience becomes one delighted unit, laughing and groaning and oohing and aahing, in the capable, compassionate hands of the writer, and happy to be there. What’s more “entertaining” than that?

I guess what I’m proposing is that we might want to assume (or pretend, or wishfully posit) that if we get our stories to be as good as we can get them to be, people will want to read them. (“If you build it, they will come”); that we assume, in other words, that making our stories beautiful is the very best, uh, marketing strategy. Is this absolutely true? No. We can all name books that didn’t find their markets originally but later were recognized as works of genius. (Confederacy of Dunces comes to mind.) But here I’m suggesting a mindset adjustment that falls into a category I think of as “self-gaming”: a way of thinking that predisposes us to success (that lowers our stress level, that gives us reasonable hope).

If we say, “I’m going to assume that if I pronounce myself a pure artist, and resolve to refine and personalize my artistic judgment, and write radically according to that judgment, then the world will respond rationally to what I’ve done, i.e., will like it” – well, that takes a certain pressure off of us. It allows us to stop wasting our energy trying to outguess the market, or by resolving to dismiss (or court) certain types of readers, or obsessing over lists of recent best-sellers, or having big internal debates about how we might take on the issues of the day and all of that.

We just have to assume the best of our reader and try to tell her something interesting.

This mindset really helped me when I was in my early- to mid-thirties and working a day job, with two kids and no money (as described in that author’s note to CivilWarLand in Bad Decline that I mentioned last time). There was so much worry in me, about whether I’d “make it” and what I’d do if I didn’t. But to be able to say to myself: “Just worry about the art and the rest of it will take care of itself,” was a huge comfort. I don’t think it’s a panacea - it won’t be true for everyone who thinks it, of course, and it might not help everyone equally. But it sure helped me. I could focus on the real problem which was, at that time, maybe a few lines of prose a day, if and when I could get to them. That’s all I was really able to control anyway, and it was nice, believing that if I just did that - did the best I could with those few lines — all would, eventually, be well.

Or, at least I’d done all I could on my own behalf.

Once Frank Conroy came to Syracuse to talk to our students and someone asked him about the issue of popular vs critically acclaimed writing.

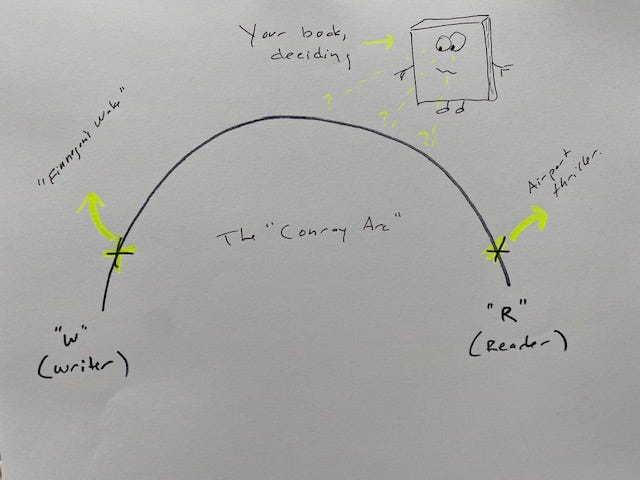

Conroy drew this big rainbow-like arc on the board. Then he labeled one end of it with a “W,” for “Writer” and the other with an “R,” for “Reader.” Every book, he said, lands somewhere on that arc. A book way over there near the “W” might be more self-referential – written more for the writer than for the reader. (Think “Finnegan’s Wake,” maybe.) A book over by the “R,” might be, say, a popular best-seller; the kind of book you find on the front rack in an airport bookstore – a book with a very large front door that anyone can easily enter.

Then Conroy said, “I bet some of you think I’m going to tell you to put your book right in the middle of that arc. But I’m not saying that at all.”

What he was saying was that, having written a book, we needed to look honestly at where it was situated on that arc and take responsibility for that. If we choose to write a book that lands near the “W,” great, no problem. But no fair complaining when it doesn’t sell. Likewise, if we choose to write a book that lands near the “R,” and sells a gazillion copies: beautiful. But no complaining if the critics don’t have much to say about it.

Now, I’m not sure I buy this idea completely. Lincoln in the Bardo got good reviews and sold well. And I didn’t compromise one bit as I wrote it and assumed all along the way that if I could get what was in my head and heart down on the page, I’d have readers enough. And that turned out to be true.

Conroy was, maybe, as I think about it, responding to a question about whether a writer should sell out or stay pure; I think he was trying to challenge the distinction, tailoring his answer to the questioner somewhat.

Conroy’s arc does a nice job of destabilizing certain notions we might have, along the lines of: “art, good/commerce bad.” Any way we want to think about our work, any aspirations we may have, are perfectly fine – as long as we recognize and take responsibility for them.

In other words, if your book is difficult and cerebral and most people can’t get through it, but you love it, and feel that you are really writing for that handful of people who can finish it – that’s great. Built into that approach (assuming you’ve taken Conroy’s advice) is a reasonable expectation re your book’s reception. You may have a small audience, or the book may be deemed not commercial enough and never get published. But you’ve already considered and accepted that.

Also, Conroy gives us a way to pivot mid-book. If we feel, “Ugh, this is unreadable - it’s too close to the ‘W’ for me.” Well…there are ways to move it toward the “R,” and we can discover them for ourselves.

It reminds me of an old joke. A guy goes into the doctor and bends his hand way back. “Doctor,” he says, “it hurts when I do this.” The doctor gives this some thought. “Don’t do that,” he says.

I suppose this goes back to last week’s advice: know thyself. Know thy book. Make decisions on its behalf as you write it. If it is too cerebral and you don’t like that, there are ways to fix it. Likewise, if you feel your book is too “easy” (too audience-aware, not deep enough, condescendingly simple): go ahead and write that book, if that’s the one you want to write. But be prepared, by Conroy, with reasonable expectations that you may not get critically lauded. And if that notion bothers you, well, you can dig into that feeling (“too audience-aware, not deep enough”) and see what it means to you, technically: how might you (you could ask yourself) make it deeper? What does “deeper” mean to you, anyway? How is it “not deep?” Why do you feel uncomfortable with your book’s current level of what we’re calling “audience-awareness?” Do you feel you’re pandering? What are you afraid of?

And so on.

I’m not sure I’ve answered the question we started with. In fact, I’m not sure there is a neat answer to this question of art vs. commerce. For me, as I’ve mentioned above - the more artful, the better the commerce, at least so far.

But for sure: life is short, art is long. It takes a tremendous amount of time to learn an art form and, meanwhile, one has to eat. At present, for the most part, writers are expected to do most of that hard artistic work while doing…other hard work. Most “other” jobs these days require and expect all of our energy. Meanwhile, we have people we care about and cars and pets and houses that need attention, and so on.

So I think it’s important to at least acknowledge that, for as long as we love and want to serve our art form, this question of where to find the time and peace of mind to do so is going to linger. It’s always good to say these things, I think, so that we can know we’re not alone in these worries, in this struggle.

I get a number of emails from young writers who have left school and are working hard and struggling to find time to write and maybe seeing their artistic dreams starting to sail away into the distance. One thing I like to remind these writers is that a writer is a writer, no matter what sort of work she’s doing, as long as she is thinking, still, like a writer: observing and mentally composing and watching the world with curiosity. Writing is a lovely, life-affirming thing to do, even if the world never rewards us for it, or never rewards us enough to allow us to make it the main thing in our lives. It's a vocation, after all, not a job – and even if we’re lucky enough to have it as our job, it’s still not a job, not really. I guess what I’m saying is that we could be as rich as Midas, sitting at a big old golden desk, with no interruptions for the next ten years, and someone bringing us healthy meals and sharpening our pencils and so on, but what makes us a writer in the moment is the state of our mind. Are we interested, curious, noticing, changing our view, always changing our view, loving the world, compelled by the beauty of language? Nothing can take those things away from us and, the truth is, nothing external can give them to us either.

Let me end by pledging to keep looking at this question in future posts. I’d like to try to talk, in particular, about the actual money part. How much money can a writer expect to make anyway? On what sort of schedule is she paid? How much taxes does she have to pay? How do advances and commissions and all of that work, and where the heck does that money go, anyway?

More about this soon…

On Sunday, behind the paywall: a new and wonderful story for us to work on together. Join us over there…

I’ve had wonderful students who got blocked-up and anxious at the merest mention of publishing – who had to pretend that publishing didn’t exist in order to do their best work.

after reading through the comments, I feel compelled to add this (kind of depressing, sorry) thought: being published (for MOST of us--perhaps not for those who end up with true fame and very good contracts) doesn't change anything. Sure, for a few moments, you feel great. Validated. It's something you've worked hard for and now--here it is! A real, live book! A few people actually buy it (or the journal you were published in or whatever). They congratulate you. You feel like you've entered a club--those who have made it. Look how smart you are! Look how others acknowledge your intellect, your humor, your ability to write! And then.....crickets. Honest to god. It ends. And you are just you again. And no one cares about your book. i can't tell you how many people have asked me what I do and I say, well, I'm mostly a writer, I wrote a couple of novels. And that's.....end of conversation. If i didn't get personal satisfaction from putting pen to paper, I wouldn't do it. Because no one cares if I write or not. My "job" is to enjoy my life. And if that enjoyment comes from writing, then fantastic! But i know that it really doesn't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world if I write or if i don't write. I'm not all that important and no one is waiting for my next book. It's a blast to get published, just like it's a blast to have any sort of success in life. But you are still you. And if you want a career, you have to manage to do it all over again, this time with expectations from others. I'm gonna post this even though maybe i should not. I know how lucky i am to ever have had a book published in the first place. I really do. But like anything, the thrill comes and goes and you are left with yourself again. My personal takeaway is that doing what you love is a great way to live a satisfying life. But it's all in the doing and not in the having done. What was the question again? Sorry, i'm rambling.

Sigh. Heavy sigh. This is my life struggle. I write this now from my desk at work. Just this morning I sent a message to a friend saying that I hoped this summer I might find my way back to some writing. The absence has been long. I hope it will prove to have been a fruitful sabbatical, but it could just be time away where I grow more and more rusty and feel less and less a writer. Breadwinner. Not sure what I am winning except keeping the ship afloat. It's a ship without a lot of art on the walls. On your recommendation I ordered Tillie Olsen's "Silences". Like her, I have long been a mother who is solely responsible for running the household. It has been about 4 years since I published anything, and over a year since I submitted anything. I take photographs these days as it is art I can make as I go about my day. I dream of retirement. I dream about days when my worry is only that I have the time to write and I am not using it! I yearn for days when I can mark my writing time in hours, not minutes. I want my imagination to dwell in a house as big as the sky. I want to run away with my obsessions and not come home until after the supper dishes are done. This work-life makes all the best bits of me smaller, and I miss them so.