AN INCIDENT

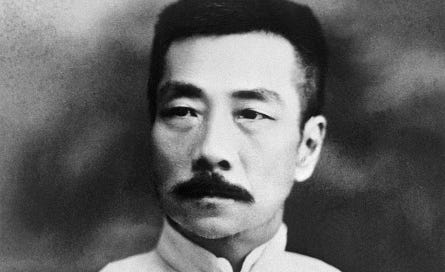

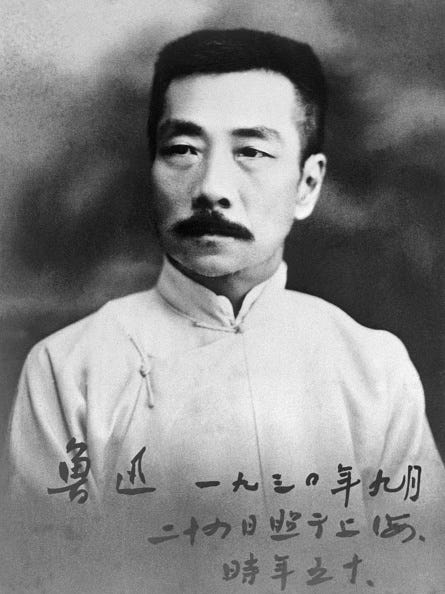

by Lu Hsun

Six years have slipped by since I came from the country to the capital. During that time I have seen and heard quite enough of so-called affairs of state; but none of them made much impression on me. If asked to define their influence, I can only say they aggravated my ill temper and made me, frankly speaking, more and more misanthropic.

One incident, however, struck me as significant, and aroused me from my ill temper, so that even now I cannot forget it.

It happened during the winter of 1917. A bitter north wind was blowing, but, to make a living, I had to be up and out early. I met scarcely a soul on the road, and had great difficulty in hiring a rickshaw to take me to S—— Gate. Presently the wind dropped a little. By now the loose dust had all been blown away, leaving the roadway clean, and the rickshaw man quickened his pace. We were just approaching S—— Gate when someone crossing the road was entangled in our rickshaw and slowly fell.

It was a woman, with streaks of white in her hair, wearing ragged clothes. She had left the pavement without warning to cut across in front of us, and although the rickshaw man had made way, her tattered jacket, unbuttoned and fluttering in the wind, had caught on the shaft. Luckily the rickshaw man pulled up quickly, otherwise she would certainly have had a bad fall and been seriously injured.

She lay there on the ground, and the rickshaw man stopped. I did not think the old woman was hurt, and there had been no witnesses to what had happened, so I resented this officiousness which might land him in trouble and hold me up.

"It's all right," I said. "Go on."

He paid no attention, however—perhaps he had not heard—for he set down the shafts, and gently helped the old woman to get up. Supporting her by one arm, he asked:

"Are you all right?"

"I'm hurt."

I had seen how slowly she fell, and was sure she could not be hurt. She must be pretending, which was disgusting. The rickshaw man had asked for trouble, and now he had it. He would have to find his own way out.

But the rickshaw man did not hesitate for a minute after the old woman said she was injured. Still holding her arm, he helped her slowly forward. I was surprised. When I looked ahead, I saw a police station. Because of the high wind, there was no one outside, so the rickshaw man helped the old woman towards the gate.

Suddenly I had a strange feeling. His dusty, retreating figure seemed larger at that instant. Indeed, the further he walked the larger he loomed, until I had to look up to him. Ar the same time he seemed gradually to be exerting a pressure on me, which threatened to overpower the small self under my fur-lined gown.

My vitality seemed sapped as I sat there motionless, my mind a blank, until a policeman came out. Then I got down from the rickshaw.

The policeman came up to me, and said, "Get another rickshaw. He can't pull you any more."

Without thinking, I pulled a handful of coppers from my coat pocket and handed them to the policeman. "Please give him these," I said.

The wind had dropped completely, but the road was still quiet. I walked along thinking, but I was almost afraid to turn my thoughts on myself. Setting aside what had happened earlier, what had I meant by that handful of coppers? Was it a reward? Who was I to judge the rickshaw man? I could not answer myself.

Even now, this remains fresh in my memory. It often causes me distress, and makes me try to think about myself. The military and political affairs of those years I have forgotten as completely as the classics I read in my childhood. Yet this incident keeps coming back to me, often more vivid than in actual life, teaching me shame, urging me to reform, and giving me fresh courage and hope.

July 1920

***

Story translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang

Published by Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1960, 1972.

For review purposes, here are the instructions I posted last time (slightly modified):

Read it in its entirety, just for fun.

Then write about it, loosely and intuitively, in your notebook. Just react to it - no need to try and explain or analyze — in whatever way feels best for you. If you find yourself at a loss, maybe consider: what did you feel, and where? (No need to worry about why, particularly, just yet).

Then let the story sit there in your mind for awhile as you go about your life. Give it a little time (a few hours, a full day?)

Then read it a second time, more slowly, making notes as you go. Maybe trying to see, lightly, what caused you to feel whatever you described in 1), above. (What you felt and where you felt it.) You might outline it, listing its main events, as a starter. The point is just to approach it with real curiosity, in your way. I’ve had students who did this by doing cartoons or maps or org-chart-like schematics. Other students made bulleted lists, or wrote full essays, or compiled a list of questions. We might think of this phase as “keeping the hands busy as the mind does its work.”

Then summarize that process, if you like, in the Comments. The main idea here is to put a little time between the initial reading and the Comments phase. The overriding question is something like, “How did this story do whatever work it did on me?” And our aspiration is to be as specific, exact, and technical as we can be.

In my next post, I’ll pick out a few things that might be worth mentioning about the story.

Share this post