I am preparing this post on Saturday and, as I’m sure is true for many of you, my mind is on Ukraine. We have an old dog here who needs a lot of care, and my back is going out, and I am in the middle of doing edits for my next book and yet can’t seem to stay away from the news, and I feel, overall, sad and ineffective.

It is a time to understand in the heart the limits of literature but also its power. No story is changing anything now. This outrage is an outrage and real people are suffering and dying. Literature is a practice that improves a culture and can make it more tender and open. But its effects lag and are approximate and tend to benefit people already gentle and inclined to caring.

And yet.

In stories we might catch a glimpse of why people do the things they do, which should prepare us to think about things more incisively and boldly when people do something that is cruel, violent, or inexplicable. Whatever we are brought to feel, through literature, about love and understanding and sympathy must take this into account: the invasion of a peaceful country by people who have somehow, it would appear, set aside love, understanding, and sympathy, or have twisted these notions into strange shapes amenable to their purpose.

Also, in this world of ours, there be monsters — the workings of whose minds are mysterious, and whose darkness (their apparent indifference to love, understanding. and sympathy) we somehow keep underestimating.

This, too, can be written about.

But what also can be written about: people fighting and dying for their freedom and the freedom of the people they love.

What do we do when notions dear to us (notions of compromise and kindness and the ultimate goodness of any human being) are mocked by events and made to feel facile? Can our understanding of these notions be expanded so that they are more muscular and useful and don’t have to be set aside or apologized for at moments like this?

I don’t have answers and am not even sure these are the right questions. But I did want to at least acknowledge the big, sad elephant in the room before carrying on with “The Stone Boy,” a story that aspires to show us, anyway, how one human heart begins the process of going dark.

One of the symptoms of feeling engaged by a story is a sense of curiosity. The story seems to pose a question. (One of the indicators of a story that is not so good is that we don’t know what we’re supposed to be curious about.)

For me, “The Stone Boy” becomes, pretty quickly, about two questions: 1) “Is anybody going to help this poor kid?” and 2) “Is this kid a sociopath, as certain people in the story seem to believe he is?”

Now, a good story is one that poses a pressing question and is shaped in such a way that goes about answering that question efficiently. That’s part of the pleasure of reading it: the story asks the same question we are asking, and we enjoy its ruthless efficiency as it pursues the answer. We might think of the writer of a good story as a creative, energetic detective we’re following around. We admire her energy and efficient method, we marvel at the quickness of her mind and the soundness of her instincts. (By the way, I don’t think we generally know what question the story is asking when we start writing. I don’t, anyway. Usually, I’m writing in an attempt to blunder into that question.)

So, let’s take a look at how Berriault has efficiently shaped her story so as to answer those two questions.

(As an aside – if you found yourself asking different questions that I’ve asked, the same exercise can be done. Examine the structure of the story and see if it seems designed to answer your questions efficiently.)

“Is this kid a sociopath?”

My short answer is: No, he’s not. He does not harbor any unusual level of resentment for his brother. The accident was just an accident. (The indications of competition/animosity/jealousy between the boys, I take as misdirects on Berriault’s part – they cause us to slightly wonder if Arnold did it on purpose and also, I think, cause Arnold to wonder this, especially once the sheriff raises that doubt in him.)

How do we know that he’s not a sociopath (i.e., that the story doesn’t intend for us to conclude that he is)? Well, when we consider Arnold’s arc, what we see is not a fixed pattern of sociopathy (he is cold and unfeeling at the beginning of the story and stays that way) but, rather, a pattern of normal feeling, delayed.

He starts out “cold and unfeeling,” to all appearances, and even until the bottom of page 278 he still “felt nothing, not any grief.” (Even we begin to doubt him.) Then, on page 278, when he thinks to go to his mother and “tell her that Eugie was dead,” he has finally come fully back to himself; the shock has worn off enough for him to feel what he should have felt long ago. He’s not a sociopath, in my view, but a little kid who took a hit too enormous for him to process in a timely manner (not a “stone boy” but a “stunned” boy).

Another argument for this view is that the “He is a bad kid and just stays that way” version of the story is more static than the “He is a normal boy who, shocked, is mistaken for a cold boy, and then becomes one” version.

The tragedy of the story, really, is one of timing. Arnold seeks consolation at a time when his mother, in her own brand of shock, is unable to give it. Next morning, somewhat recovered to herself, she asks “humbly” what he’d wanted, but it’s too late – the rebuff of the previous evening has done something to Arnold, who is now no longer seeking warmth, and maybe, we feel, never will again.

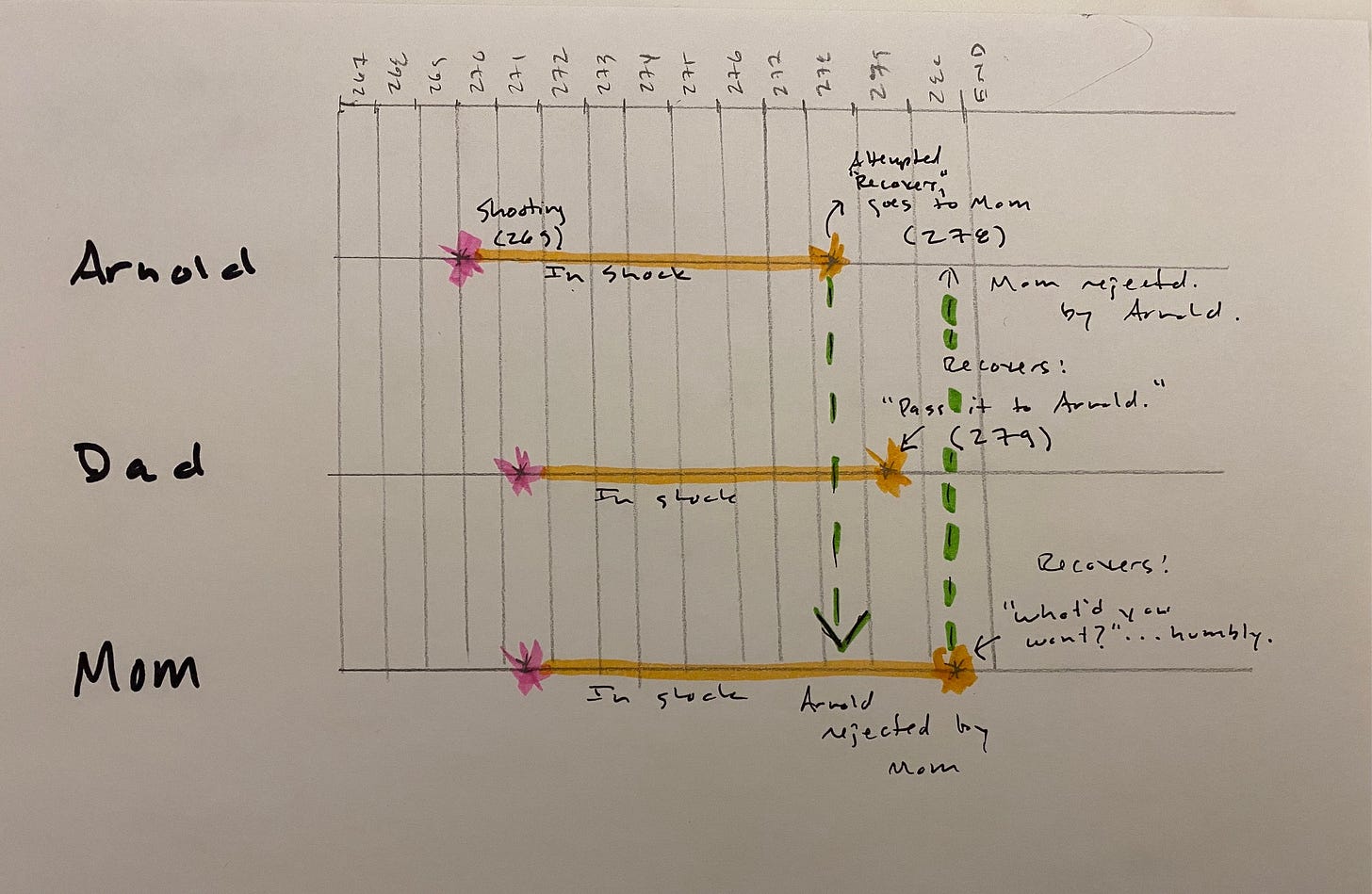

Each member of the family (Arnold, mother, father) goes through the same arc: shock, coldness, recovery.

The tragedy is that the three incarnations of the pattern are offset in such a way that no comfort can be given when it is needed.

None of the above is told overtly. It comes to us by way of the timing of the story’s events – this offset in the three different patterns (Arnold’s, dad’s, mom’s) of “shock, coldness, recovery.”

If inclined, a person could probably graph this.

“Is anybody going to help this kid?”

The short answer, as we know, is: “No, they are not.” On the contrary - the reactions of Arnold’s family and his community have the effect of piling a tragedy (the shunning of Arnold) on top of a tragedy (the killing of Eugie). By the end of the story, both of those living, lovely, active boys from the beginning of the story are no more.

But Arnold, at least, could have been saved.

I’ve said in other places that a story is basically a rhetorical machine - it’s a way to put an idea into play and then, through structure and plot, work through that idea. Often, the result is not an answer, as such, but an elevation of the original question. Here, we ask if anybody’s going to help Arnie, and see that the answer is no, and this causes us to ask, “Well, why not?” Or, if you will, “Well, how not?” That is: “How is it that sometimes, in this world, those who need help don’t get it?” How, precisely, does that happen?”

Once Arnold has killed Eugie, the rest of the story is really just the systematic introduction of a sequence of possible helpers: his parents, Uncle Andy, the sheriff, the community.

We look, naturally, first, to his parents. What do they do?

First (page 271) they don’t believe that Eugie is dead. Then (pages 271-272) they basically forget about him. Then his father…takes him down to the police station. Note that, over this stretch of pages (271-274) Arnold’s father never addresses his child directly, though there are ample opportunities for him to do so (as they sit on the bench at the police station, for example). He does stare at him “in a pale, puzzled way.”

I think that the father (like the silent mother, like Arnold himself) is in shock. When will he snap out of it? Later, maybe. A possible thaw begins on page 279, when the father instructs Nora to pass Arnold the pitcher. But it’s late, so late.

(As an aside – an interesting assignment might be to get highlighters of different colors and track every mention of the Possible Helpers in the story (mom, dad, Andy, community), then boil down each moment into its essential action (“Dad tells Nora to pass pitcher”) and see if you can infer the resulting simple arc – the way each action represents an inflection point for that character. It’s the accretion of these inflection points in sequence that produces the meaning of the story. And if you do this, you’ll see the offset mentioned above.)

One of the aching pleasures of the story, for me, is the way I keep waiting for Arnold’s parents to step up, show some love for him.

But they never do, not really, not until the end, and then only tentatively.

In the absence of the mother and the father, who else is there who might help Arnold? Well, that crummy sheriff and the miserable Uncle Andy.

Uncle Andy is a character who can teach us a lot about what a “fictional character” actually is.

Let’s note that he has one function: to lead the charge against little Arnold. Why does he dislike Arnold so much? There’s only one reason given: he “had been fond of Eugie because Eugie resembled him.” Well, that doesn’t seem like much of a reason. (We can easily imagine a story in which Andy is fond of Eugie and yet, when Eugie is killed, doesn’t feel inclined to demonize Arnold.)

So, Andy becomes, for me anyway, a sort of archetypal, almost Shakespearean, figure: He Who Despises for No Reason. We might also note that we get zero backstory on Andy. We don’t know if he’s good at his job, whether he loves Aunt Alice, whether they have kids of their own, if he had a difficult childhood — none of that. He’s an important character but what we know about him before he starts to act (at the police station) is one thing: he was fond of Eugie because Eugie looked like him. That’s it. He’s not really a person; he’s a function-fulfiller. He exists to be turned against Arnold by the sheriff (the sheriff confirms Andy’s pre-existing bias) so he can then turn the community against Arnold (in that scene on page 277).

We might remember this, the next time we are, in one of our own stories, trying to make motivation by “filling in backstory.” Andy is a vital character not because we know a lot of meaningful things about him, but because he has a strong inclination —in this case, to unfairly dislike and judge Arnold. And that strong inclination causes him to act, and to cause something – the alignment of the community against Arnold.

And this then causes what I feel to be the main, most consequential, saddest action of the story: the way that Arnold then begins to turn against himself, asking about himself the same questions we are: “Am I a sociopath? Is there anyone who might love me enough to help me?”

So, if we were writing a guy like Andy, we might find some comfort in thinking of him that way – as a function-fulfiller. What’s interesting – and I feel this in Shakespeare all the time – is that, if a character fulfills a vital function (especially if it’s a function for which there are approximate real-life examples), we readers supply everything else. (We don’t really care why the Macbeths are bad. We just enjoy watching their badness play out – the play exists as a dramatization of the process and costs of “going bad,” we might say.)

If we look at the beginning of the scene of Arnold’s grilling (page 273-274) we see that it is the sheriff who first introduces the notion that Arnold might be a bad person, with the question: “Were you and your brother good friends?” (The father slightly rises to Arnold’s defense here, with, “Seems the hammer must of caught,” but then is (too easily) persuaded by Andy and the sheriff’s subsequent negative view.) Then the sheriff poses the fatal question, of why Arnold went off to pick peas and, not satisfied with Arnold’s answer, pronounces his verdict: “the most reasonable guys are the mean ones.”

Note here the tight cause-and-effect: Andy comes in preferring the dead Eugie but not yet fully inclined to act against him. The father comes in stunned and neutral. Andy and the father await the sheriff’s verdict. It comes: this kid is bad. The father, persuaded, or at least cowed, fails to rise to Arnold’s defense. And when the sheriff asks Arnold why he went to pick peas, his father, instead of having a ready, fatherly answer for this, looks at Arnold “curiously.”

In this atmosphere, Andy’s ambient dislike of Arnold is given permission to surge forward. The two men leave the police station in a different state than when they entered. “His uncle’s eyes had absorbed the knowingness from the sheriff’s eyes. Andy and his father (italics mine) and the sheriff had discovered what had made him go down into the garden. It was because he (Arnold) was cruel…and didn’t care about his brother.”

The scene in the police station models a sort of viral negativity– it shows how darkness self-propagates. The sheriff tips Andy, who tips the community, and this consensus fatally delays the restoration of the parent’s love for their son.

Imagine a story in which the sheriff was a kind and compassionate man, who had once done something similar to what Arnold has done.

Imagine a story in which Uncle Andy preferred Arnold over Eugie.

So, Berriault is telling a very specific version of this “kid kills his brother” story: the one in which the system into which Arnold was born is somehow pre-inclined to unkindness (or denial, or coldness, or emotional remove, or however we want to say it). Behind the story I hear Berriault saying, “This is how it is sometimes, when it’s bad.” That is: “It’s not always like this, but it sometimes is.”

There’s so much loneliness in this story, so much enforced emotional “independence.” This community is not really a community at all, but more like a collection of desperately self-protective people, averse to tenderness, therefore infinitely vulnerable when misfortune strikes.

And the story shows us the process by which one more such person might be created.

But, even in its last sentence, Berriault keeps the story dynamic and full of possibilities, with the phrase “frightened by his answer.” He might have been sure of his answer, or full of rage. But that phrase leaves open the possibility that his fear of his own answer may translate into some rapprochement with his parents, if only they can rise to the occasion.

Can they? Will they?

We really can’t say, and this gives the story its feeling of openness and uncertainty and even terror at the end. It feels like life: endlessly uncertain, so much always at stake.

George, I feel for you taking care of an old dog. We're doing that here, too. And, apropos of the opening of this post, Ilya Kaminsky tweeted this morning:

"Me, writing to an older friend in Odessa: how can I help, please let me know I really want help

He writes back: Putins come and go. If you want to help, send us some poems and essays. We are putting together a literary magazine.

And, that is in the middle of war. Imagine."

William Carlos Williams: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”