Like many of you, I expect, I’ve had the subject of schools very much on my mind this week. What a magical and, perhaps taken-for-granted thing it is, for one group of people (students) to go off to a place, a safe place, and there meet another group of people (their teachers) whose vocation is to pay positive, hopeful attention and thus make those students better, stronger people in the world.

One of the best things about being published is that sometimes I’ll hear from a dedicated teacher who has decided to teach my work to his or her class.

What a thrill that is.

This week, I wanted to share with you a particularly lovely exchange of this sort.

**

On April 22, I got a note from a certain Thomas Lewandowski, who teaches high school at Springdale High School in Arkansas. He’d assigned his students Lincoln in Bardo and was wondering if I might be able to do a Zoom call with them. I couldn’t do that – we live way up in the hills and Zoom on our (satellite) internet is slow and sometimes outright Escheresque – but I offered to take some written questions by email, if they were up for it.

They were.

**

Soon, I got the following email from the class:

(Breakfast Club music playing in the background).

We are juniors at a very diverse school, Springdale (Arkansas) High School. (Maxon “Kimo” Beasha)

We are an aspiring young group of students, reading a variety of books for our English curriculum. (Kayla Love Souvannarath)

80% of us are first generation Americans joining the cacophony. (Mr. Lewandowski thinks we should use this word). 10 of us, including our teacher: 50% Hispanic, 20% Pacific Islander, 20% White, 10% Asian.

Girl power. (Jennifer Anay Reza)

We are I.B. students. I.B. = International Baccalaureate = AP on steroids. (Juan Pablo Lemus)

We are sacrificing our sleep, social life, mental health, free time, and our overall welfare for a quality education & our future. We are some of the hardest working high school students in America. We come from middle to lower income households and go to a public school in the state with the ninth worst test scores in America. These are our questions, Mr. Saunders. Thank you.

*

Well. That was hard to resist.

I replied:

Hi all,

Just to say I am in receipt of your lovely note and....will get right to it.

What a refreshment, to have homework again this late in life. Wait - did I say "late?" No. This "mid" in life. Yes, that's it.

To have homework this "mid" in life.

Seriously - so moved that you read the book and will get you my best answers soon.

Yrs, warmly,

George

(Later, Mr. Lewandowski filled me in on the class: “These kids are amazing. It's an honor to teach them. I get to teach what I want and how I want, which also makes me extremely lucky. It's you, Wisława Szymborska, Ursula K. LeGuin, Murkami, Octavio Paz, D.F.W., Milton, Shakespeare, Zadie Smith, and a few others. I teach each cohort for two years, 10-20 students. We study 13 major works, and I try to teach them how to write.)

So, after sending that email above, I had a look at the questions and…well, they were so good, I got right to work, and sent the following reply later that night. (I should probably mention that if you haven’t read Lincoln in the Bardo, what follows might not make much sense - I was trying to pitch it to someone who’d just finished the book and had it fresh in their (brilliant, young) minds. Also, forgive any looseness - I was emailing and present it below pretty much as sent…)

The Q&A:

Why did you choose the civil war as an entry point for your exploration of American identity?

Honestly, simple fascination. I’ve always had a thing for that period and I honestly don’t know why. I am tempted to think: Reincarnation. I must have been alive back then. I mean, I can come up with all kinds of “smart” reasons, but the real reason was that I sensed, when I thought about that period and this incident, some joy on the horizon. And here’s something we aren’t taught in school, generally (although I suspect Mr. Lewandowski, being, seemingly, an excellent teacher, does teach it): “joy” and “art” are inextricably linked. It’s hard to do anything beautiful without some joy going on. Imagine your favorite album – any joy in that? Do we think the artist was having fun? Of course she or he was. The truth is, it’s really hard to proceed on any other basis. We sometimes are told, or made to believe, that art is about planning, about knowing what one wants to say, about being smart, having a theme – but in reality – in the actual doing of it – you have to have some love. You can’t write 300+ pages unless you are being led by something, something that you can’t resist. And you don’t need to know why it’s interesting to you – just that it is.

So – the Civil War period, for reasons unknown, lights me up. And I trust that.

What does the fence (pg. 223) represent regarding America’s history?

Well, first, it’s there because…I needed it. Well, and because, there IS a fence, at Oak Hill.

But here’s how it actually happened. (I like to talk process for any writers in the class but also because it’s more honest.)

At one point, I thought to myself, “Look, you’re an old white guy. Let’s not run the risk of appropriating anyone else’s experience. And look, it’s possible (to avoid this problem altogether): at the time of the story, Oak Hill was an all-white graveyard.” But then, later, I thought: “Huh. You’re an old white guy writing a book set in the time of the Civil War, in this (yes) cacophony of voices – but there’s not a single Black voice in your book? That’s even worse.” (There was, actually, one Black voice, that of Elizbeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s seamstress and sometimes confidante, but her race is not identified in the book.)

OK, so there I was, but then again: it’s an all-white graveyard. How do I even get a Black voice into the book? Also, all this time, I had the Barons in and out of the book and couldn’t figure out how to get them good and finally in – and I wanted them in, because I found them funny (Oak Hill was also an upper-class cemetery and they couldn’t have afforded it). Somewhere along the line I hit upon the idea of what was called a potter’s field – a mass grave. We had one near where I grew up in Chicago, out back of a big public hospital – there was a famous incident where, after a flood, a ton of bodies came to the surface – creepy! So I thought: “OK, maybe I can put a mass grave adjacent to Oak Hill. And…I did it. But that Oak Hill would have been prohibited to both the Barons and the Black ghosts – hence the fence. And once you make something like that, that fence, you have a chance to give it metaphorical meaning – or, you know, it has that automatically: it’s the thing that separates this from that. Privileged from not, and so on. But it’s also, importantly, a real fence…

One other weird fact – there was, in fact, an all-Black graveyard next to and not far from Oak Hill – but I missed that in my research. I don’t think it was right next to it, but very nearby – but I could have used that, and had a wider range of Black characters. But I only found out about it a few years ago, after the book came out.

Where did the Reverend go in the end? Why wasn’t this included in the book?

Right. My feeling is, he goes to….whatever the good place is. (Not The Good Place, with Ted Danson. But maybe similar.)

Sometimes, especially with a wild book like this, the writer’s job is to listen to the book and see what it’s saying. Here, the book is saying that no one gets to report back on what happens after that matterlightblooming thing (when they “go” in this way, their narration ends). We don’t want to make an exception for the Reverend just because we care about him. What comes after sort of ascension phenomenon is…roped off. The integrity of the book demands that it stay so.

But here’s why I think a close reading of the book tells us that the Reverend was saved.

The author (me, that is) goes to great lengths, there on pages 273-275, to have the Rev save Willie. If that makes no difference to his fate….why did I show it? Secondly, just before the attempted escape, he says (page 271) that faith is to believe that God is “ever receptive to the smallest good intentions.” That’s why he tries to save Willie – he thinks it can still make a difference, can alter his fate. So, it’s something about narrative efficiency – the author (still me) would not have told you those things if they, in fact, were to have no effect on what happens later – that would be inefficient.

Something like that.

Another way to say it – if the Rev was supposed to continue to be damned, he wouldn’t need to have done anything in the pages between his scene in hell and the end of the book.

That is: why would I have put all those incidents in there if they weren’t meant to cause something, to lead to something?

I wouldn’t have.

We do know – from his line on page 275 (“That dreadful diamond palace” that he made it that far.

I also don’t know, by the way, what he did that was so wrong (i.e., that got him damned). And I don’t know it (and you don’t) because he didn’t. He didn’t originally, because I couldn’t come up with anything – whatever I thought of seemed too literal, like: he dodged his taxes? Really? That’s what did it?

So, I realized that I, for the sake of the book, couldn’t come up with, or reveal that information. And that was a drag, for a long time. I knew people would wonder. And to just avoid that question would be a defect in the book. And then – late in the game –on page 265 – an opportunity presented itself, as the Reverend tries to remember why he was damned – and can’t. So that (to me anyway) made it all make sense – we can’t know because he doesn’t. He used to, but now he doesn’t (he forgot) and he forgot for a reason in which we already believe – the memories of these bardo beings get depleted, by the process of them trying to stay. (The book has been saying and showing that for a long time – the ghosts keep telling the same stories over and over again, etc).

And just like that, what was possibly a fatal flaw in the book became (at least in my read of it) a virtue. Hooray! What a relief.

Based on what we have read, we believe Hans Vollman would be your favorite character. Is this true? If so, why?

He’s sort of like the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, yes. I guess so. It might be just that I thought him up first. He was in a (much) earlier version of this that I wrote as a play. But Bevins is a close second.

Why is there no “true” narrator in the novel?

Again, the most truthful answer is that I found it more fun (more honest, easier) to let these hundreds of people tell the story. But also – isn’t that what the world really is? Billions of viewpoints, wandering around, sneezing, having lunch, believing themselves to be central and permanent? I think that’s how God sees us: all of these lovely subjective little doofs, trying to be happy, win, have fun, avoid blame, etc. So I find it easier (more honest) to write that way – I think that’s how things really are, seen truthfully, as opposed to one, omniscient narrator. “The truth” is….everything that is happening right at this instant, and including what is happening inside every mind. There is no fixed truth, outside of the mind thinking it.

Would it be fair to say that one of the things the novel explores is the intersection between race and class, primarily through the Barons and their positive interactions with Elson Farwell on the other side of the fence? Are we correct about this? Is there some understanding you hope a reader would take from the novel in this regard?

Yes – to me, what it explores is that on the earth, at a given time, certain people enjoy advantages that others don’t. I felt there was something energetic about putting some of the people who were disadvantaged in that 1860s life into contact, after death, with some of the people who’d been advantaged. Surprise, surprise: bias survived death.

But, to be honest, I always find myself slightly frowning at the word “explores.” Why? Well, I think that feeling of a book “exploring” an issue is a byproduct – any good book is going to be felt to be exploring all sorts of things, of course. But from the writer’s standpoint (or this writer’s, anyway) that’s not really the goal. The goal is to make you believe that these things are actually happening AND to make you feel something because of it. That’s, like, 90 percent of what I’m trying to do, maybe more. So, I put some Black ghosts in there for the reasons mentioned above – practical, functional reasons – and then I know that, OK, the book is now “about” race. What’s it going to say about it? I don’t worry about that. I let the book tell me.

Then I put some poor white people in there – real partiers, who, unlike the Black ghosts, caused a lot of their own problems on Earth – well, now the book is “about” that too – about the fact that some people just seem to be born with karma that makes them live in the wrong way and hurt others (like the Barons hurt their kids) and themselves. That’s interesting (because we all know people like that) and it engages our interest (for the same reason, and because we wonder: What does the afterlife do to, or for, those people)?

But I think about stories more like that – not so much about exploring issues or themes or even making political sense – I mean, I hope it does, and trust that it will, have political meaning – but if so, it’s not because I consciously put that meaning there, but because I paid attention to my story and made sure that it was honest and made sense. And the “meaning,” and any emotional power the book might have, are natural outcomes of that. The book seems to sort of spit those meanings out, all on their own.

With this book, there was this amazing three months one autumn as I was finishing it, where all of the bowling pins I threw up at the beginning just started…landing. The puzzles inside the book answered themselves. Things I’d randomly introduced four years earlier started making profound sense. It was, maybe, with the exception of my wedding day (35 years ago TODAY, btw) and the birth of our two kids, the most gloriously alive I’d ever felt.

And just imagine – now, six years later – a group of incredibly bright and generous young people in Arkansas are reading it and asking amazingly smart and moving questions about it.

Is that a nice life or what?

All the best and thanks for reading my work,

George Saunders

To which the ever-generous Mr. Lewandowski replied:

Mr. Saunders:

You have brought me great joy this morning. The students learned a lot in developing those questions. Your response was incredibly generous.

Have a wonderful trip. I hope you are going someplace full of fun, adventure, and relaxation.

Keep doing what you are doing, sir. You are a positive energy, much needed in our world.

Just for fun: Have you read Annals of a Former World, by John McPhee? It's one of my other favorite books. Contemplating deep time, for me, is a form of meditation.

Again: thanks!

Just, wow.

No, Mr. Lewandowski, the wow goes to you and your students.

I am finding this world we’re in increasingly confusing. Sometimes it feels like our systems are breaking down, generosity is fading, the bad people are winning, and so on. And then something like this exchange happens, and I realize that goodness – however we want to define it – is profoundly incremental. We make this choice rather than that one; we believe in something and live into it, even in the smallest way; we err in the direction of caring and trust. I might, on a given day, have a feeling that our educational system is going downhill. Then someone like Mr. Lewandowski and his students appear. And I think: Well, all systems (any system) are only kept afloat by individual acts of care and heroism and engagement - a kind of viral transfer occurs of the essential values. Mr. Lewandowski’s students have found out, I’m betting, wonderful things about themselves and their minds as they worked through that ambitious curriculum, things that Mr. Lewandowski is not bringing into being, but affirming, or blessing, by his attention - and now his students get to move into their lives in that switched-on state, awake to their own abilities to analyze and discern – to their innate compassion and alertness and interest.

And here they are, by the way:

Bravo to Mr. Lewandowski and his students (and to his wife, Karine, also a teacher (of second graders) and to all the other teachers and classes with whom I have so pleasurably corresponded in the past (Hi, Ms. Schanz of Oak Forest High School, in Oak Forest, Illinois! Hi, Mr. Jennings of Affton High School, in St. Louis, Missouri!).

And a special thanks, and big love, to all of our teachers, everywhere.

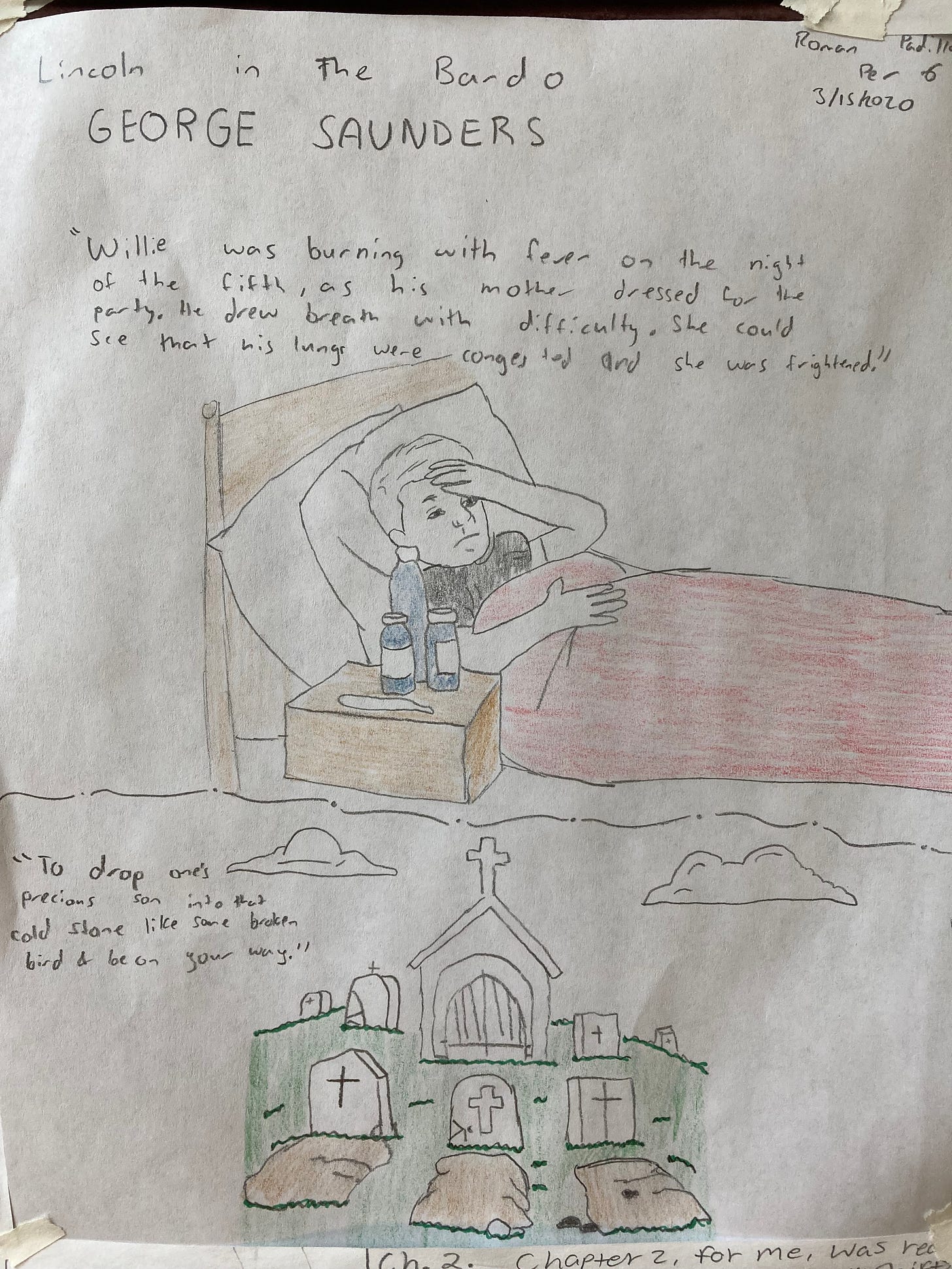

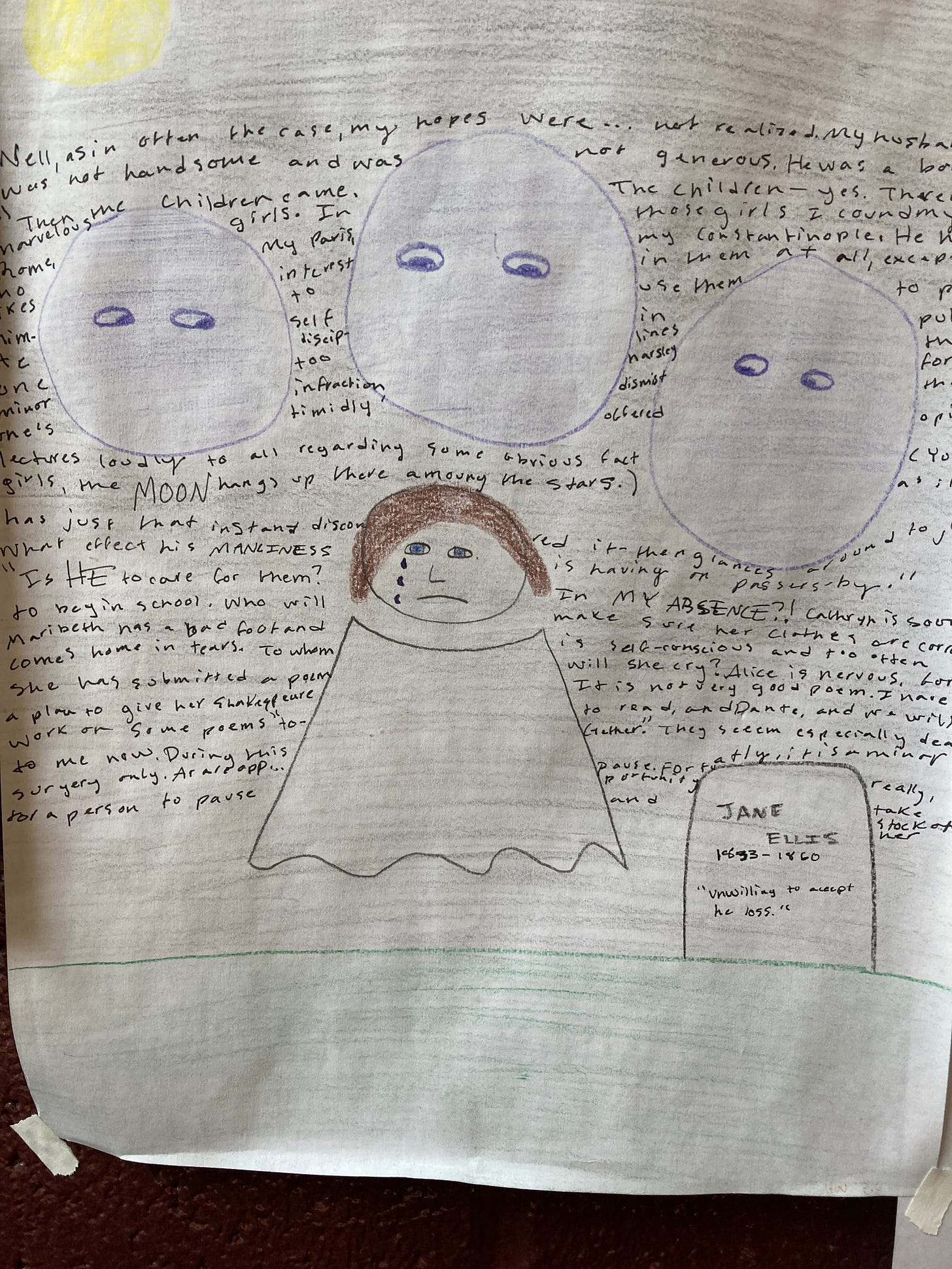

And here is some Lincoln in the Bardo-inspired art work done by members of the S.H.S. class of 2022:

On Sunday, behind the paywall, we’ll do another session on an aspect of “I Stand Here Ironing.”

Thanks for being here.

This post, as the kids say, hit me right in the feels. I didn't even make it past the first sentence before the weeping set it. Thank you for sharing this with Story Club, George, and Mr. Lewandowski, if you read this, thank you also. You sound like a wonderful teacher and this gift of guided reading, of trying to expand and make sense of the world through stories and writing, is no small thing. The teachings of my favorite educators have accompanied me throughout my life, as I feel certain the work you're doing with your students will accompany them. I feel certain they are all finding their own voices in the cacophany. (I feel a pang of envy looking at that reading list. Why couldn't I read books like these in high school? And "Annals of the Former World" is stunning).

Thank you for making me feel hope, in a week when I felt short on it.

(P.S. Happy wedding anniversary, George! We would have forgiven some radio silence, I'm sure, but as I've said before--you're too good to us. Thank you!)

Hi George Saunders, thank you for enjoying my work! My name is Henry Wilson and it was such a high honor for you posting it! I'm not the best drawer of all time, but that scene and character opened my eyes to the true, unbearable reality that is grief so true that it is near impossible to ameliorate. Thank you!