Forgive this longish post. But we’re trying to settle a big question:

To start, let’s ask ourselves an odd question:

Did Babel, the author, have to know whether the couple had sex or not?

I say yes; otherwise, it would be impossible for him to “tune” the surrounding story sufficiently.

That is, these are all different stories:

A young man has a flirtation with his employer, that comes close, but is not consummated, because of his awkwardness, which turns her off at the last minute.

A young man has a flirtation with his employer, that comes close, but is not consummated, because he is too drunk and nervous and can’t perform.

A young man has a flirtation with his employer, that is consummated gloriously.

A young man has a flirtation with his employer, that is consummated, but is kind of meh.

And so on.

The point is, if we accept the aspirational idea that a short story is a beautifully tuned, organic system in which every element is humming and resonating and in touch with every other element, then the writer (as Babel himself once put it) “must know everything.”

Otherwise, how can he edit/tune/revise all of the lines before and after the sex or not-sex?

(Fitzgerald had to know whether Gatsby died in that pool in the end. If he wasn’t sure, he wasn’t sure which story he was telling, and would not have had the tools to revise the rest of the book into perfection.)

So, let’s assume that, if we brought Babel back to life and asked him whether the narrator and Raisa had had sex, he would be able to respond with a simple “Da,” or “Nyet,” before glancing around at all of the high-rises and the people strolling through the graveyard on their “cellphones” and then dropping back into his grave, likely, knowing him, with a few well-turned celebratory sentences already running around in his head.

Why, then, does our group (so rigorous, insightful, and energetic) seem to have differing opinions on this question?

Well, the answer is likely: We can’t be sure what Babel intended because Babel was doing his best to be subtle. Or, maybe, tactful. He was, maybe, trying to keep a sentence like, “And then: we DID IT!” out of his story.

He was, that is, doing a version of something I imagine I’ve seen in some 1960s movie, where the couple is about to kiss, and then we cut to a scene of fireworks and madly chirping birds and then cut back to find the couple in bed, both smoking cigarettes.

Now, some of us have said that it doesn’t matter, whether they did it or not.

Personally, I feel (for the reasons mentioned above) that it does matter, very much.

And here I’d also like to introduce an important literary distinction, between ambiguity and vagueness.

We aspire to ambiguity (the same definite event yields different feelings and possible interpretations) and try to avoid vagueness (we can’t tell what the heck happened).

Imagine a version of Gatsby where Gatsby might, possibly, be dead in the pool, but we aren’t really able to know, and, if he is in there, we aren’t clearly told who did it.

That (in my view) is a lesser work of art – it is less worked-through, less infused with the author’s vision.

We may differ about what Gatsby’s death means – and that’s the beauty of it. His death can legitimately mean many things, all at once, all of them true. That’s “ambiguity.”

(Not knowing who it is floating in that pool is “vagueness.”)

So, my view is: we have to decide whether Raisa and the narrator did it or not, in order to judge whether the rest of the story is successful, and what, ultimately, it means.

For what it’s worth, a quick Google search indicates that critics (some critics, the ones who came up first, anyway, ha ha) feel that yes, they did, they did do it, including:

Peter Orner in The Paris Review, here. (“The Babel character and Raisa hook up on the couch, in the throes of their mutual literary passion.”)

…Barry P. Scherr, writing at Encyclopedia.com, here. (The narrator “apparently seduces her.”)

…Charles Rougle, here. (He “evidently seduces her”)

…and Alexander Zholkovsky here. (“…the young narrator impresses with his verbal prowess a rich woman who has hired him to edit her translations from Maupassant and makes love to her in what amounts to translating Maupassant’s fictions into real life.”)

Do we care what the critics say?

Well, sort of.

But we’re going to want to work through it ourselves.

Otherwise we won’t learn anything from it.

So, let me, first, in a spirit of openness, confess that I am firmly on the “Yes, they did it side.”

But I want to stress that what’s useful about this kind of discussion isn’t, really, the final answer, but what the discussion tells us about the short story form, and our expectations of it.

So, let’s work through it.

First: I ask if the ending of the story has more power if they’ve had sex or if they haven’t.

To me, because the whole story has been building up to this, I think more would have to be made of it not happening, if it, in fact, didn’t happen. That is, the reason for it not happening (given that it seems so meant to happen) would then become load-bearing: it would be, more than it seems to want to be here, what the story is “about.”

Also, if all signs lead to doing it (he’s willing, Raisa’s willing) I’m not sure knocking over a bookshelf is going to change the direction of things. It’s possible, of course – the damage wakes Raisa up to how reckless all of this is – but since we don’t get a single phrase indicating this reaction from her, I tend to reject it.

Imagine a story in which a couple of friends dream and plan and save money and make elaborate arrangements to go to Paris together.

If they don’t go, we expect to hear about why not. That becomes thematically important, given all the reasons we would have heard about why they wish to go.

One passage that weighs heavily on me in this context is the one concerning Tolstoy – the narrator’s facile rejection of Tolstoy (who had actually, unlike our feckless young narrator, written great things, been to war, a large family, become world-famous). This tells me 1) that Babel is being somewhat ironic/satirical toward his young character and 2) that the narrator is anxious to put some experience under his belt.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that he would succeed in having sex with Raisa. but if we consider the two possible version of the story:

Young man in search of experience has one, then processes that/this expands his worldview, or

Young man in search of experience continues to not have any.

…the first seems, to me, more dynamic than the second.

That is, he aspires to be like De Maupassant, succeeds – and it doesn’t do for him what he thinks it will. Or: it opens his eyes to what “experience” might actually mean in the world.

Whereas, the “Young man in search of experience continues to not have any” version would seem to want to say something more about the “why” of that fail – what trait (that has, so far, been dooming him to a life poor in experience, continues to pertain that night?

And when I hold that up against the events of the story, nothing occurs to me – no satisfying answer comes to mind. He got too drunk? He was physically awkward? I find I can’t connect those miscues with whatever has been inhibiting him in his life so far. So, it all falls a little flat on the meaning front.

That is, it doesn’t seem, to my mind, to speak in an interesting way to the ending of the story.

Second, I look for evidence in the micro-shadings of the language around that moment.

At the top of page 76, we get the detail about Raisa’s husband: “His eyes wandered, the fabric of reality had broken for him.” This embarrasses Raisa. The fact that Babel tells us this tells us that Raisa is, in a sense, unpartnered. I add this to my understanding of the story…

On the night of this fateful visit (further down on page 76), the family leaves the house. I don’t take too much meaning from this. It could be as simple as: she has work to do and opts not to go out with the rest of the family. But I do note that she knows that she and our narrator will be in the house alone and has no problem with this.

They get drunk and begin role-playing (77); they have knowingly crossed the line into something personal/flirtatious.

The chambermaid “disappears (78).” She doesn’t seem shocked or dismayed. This suggests to me that maybe (maybe?) she’s been here before; maybe Raisa’s situation with her husband has inclined her to take lovers. (There’s no evidence of this in the story but, somehow, I feel this as a possibility.)

So, all of this, inclines me to think that, at this point, both of them 1) understand that something sexual/romantic is unfolding and 2) are O.K. with this.

Working down the rest of page 78:

Raisa “collapsed on to the table with a roar of laughter…” (This tells me she’s still “in.”)

After the charged line “a lad and a girl need no music,” Raisa hands him another glass of wine: another way of saying: “Yes, I know where we are, let’s carry on.”

I read the line, “Aren’t we going to have a bit of fun…” as coming from the narrator, directed to Raisa.

But it’s interesting: the Considine translation has it like this:

The buggy was harnessed to a white nag. The white nag, its lips pink with age, walked a slow walk. The joyful sun of France embraced the buggy, shut off from the world by a faded brown cover. The young man and the girl-they needed no music.

(That is, no quotation marks, and so maybe this isn’t being spoken aloud.) And then, l in the Considine, there’s a narrative break (that is missing in the McDuff) before we go on:

Raisa handed me a glass. It was the fifth. "To Maupassant, mon vieux!" "Aren't we going to have some fun today, ma belle?" I reached over to Raisa and kissed her on the lips.

(NOTE: In both translations, it’s a little unclear who says, “To Maupassant!” and who says, “Aren’t we going to have some fun today?” To my ear, it matters. I think it’s supposed to be her who makes the toast and he who asks about “having fun”…and then he follows this by kissing her. She accepts the kiss and “mutters” the line, “You’re a funny one” or, in the Considine, “You’re so funny.”)

Then Raisa staggers back against the wall, or “presses herself against” the wall – both of which feel to me like some form of consenting/offering oneself up, especially in light of the “bare arms,” somehow.

Then, I hear that “please sit down” line as coming from Raisa – she is consenting to, and accelerating, the sexual role-playing.

At this point, I assume it’s full-speed ahead for both of them.

And I might just note here, again, that, since the story is indicating that “sex is forthcoming,” if, in fact, no sex proves to be forthcoming, that is going to be load-bearing: it’s going to be a big deal, a disruption of our expectations – and therefore a lot of the story’s meaning is going to be lodged there.

This reversal will be felt to be what the story is “about,” in other words.

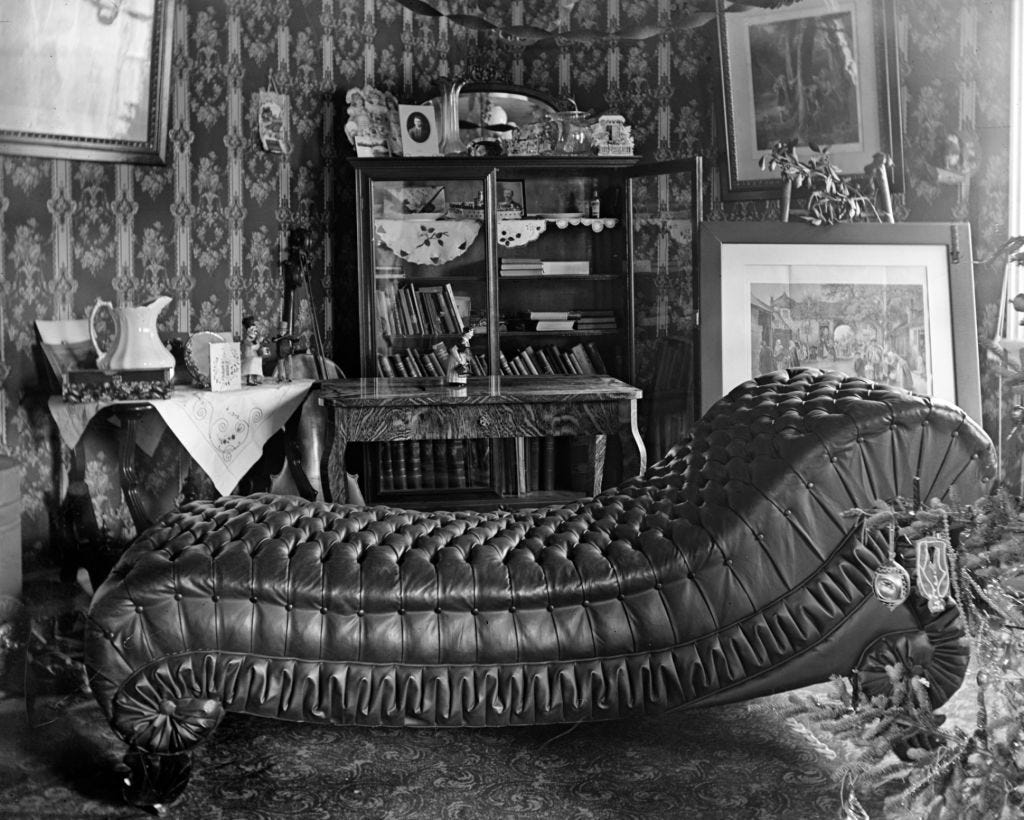

She now directs him to a chair or “points to the reclining blue Slavic armchair” in the Considine. (McDuff has this as “sloping” but “reclining” tells me more directly what she has in mind.)

Now, it’s not entirely clear how the two of them have been arranged, furniture-wise, through pages 76-78, i.e., since his arrival. There is a mention that Raisa is in an “armchair” (page 76) and so I assume that all during their talk, he has been too; they’re sitting closely together but in two separate chairs. (He has to “stretch over” to Raisa to give her that kiss on page 78, for example.)

So, I think this “leaping up” that he does now is him rising from his chair to get over to that reclining armchair.

In both versions, after an observation of that sloping/reclining armchair, the narrator indicates that he stumbles toward it. Then, after, “The night had placed under my hungry youth,” he “leaps up”…and knocks something over.

Considine specifies “the armchair” – that is, the chair he is making his way toward. It’s funny: in past, less close readings, I’ve always assumed that the chair that gets knocked over is the one he’s been sitting in – and I’ve always read this as a sort of “enthusiastic” leap, an “Aha, this is going to happen!” leap, that tips over the chair he’s been sitting in all along.

But no: he’s already left that chair (to do that stumbling) and now knocks over the target chair, i.e., the sloping/reclining chair Raisa intends him to recline on, so that, presumably, they can get the party started.

So: he’s knocked over the chair upon which they’re supposed to do it, and also the bookshelf, and now we get to the crux of the matter:

“…the white nag of my fate moved slowly on.

“You’re a funny one,” Raisa growled. (Or, in the Considine, “You’re so funny.”)

Several of you have beautifully unpacked this line about the white nag. The only thing I’d like to add is that there are basically two options here:

The “nag” line and “You’re a funny one” are both said pre-sex (or, pre-not-sex, if you’re of that camp).

The “nag” line indicates that the sex begins and the “You’re a funny one” growl happens during the sex.

I’ve always read it that the sex happens after the second “You’re a funny one,” in that white space before we get “I left the granite house.” It’s just omitted in the text (cue the fireworks) for, as mentioned above, reasons of subtlety or propriety.

(We might, for comparison, recall that scene in “Lady with Pet Dog,” in which, during the sex, Chekhov steps in and describes Gusev’s taxonomy of past affairs…and then he concludes this by having added this new conquest into that taxonomy – or, actually, creating a new category for Anna.)

Any readers of Russian out there who can give us a little more feeling of that word, “growl,” and its implications in this context? I read a “growl” at that point as being sexual – the lowering of the voice, etc. (“Mutters,” less so.) And I think that if that knocked-over armchair and bookshelf had been discouraging to Raisa’s intentions, Babel might have indicated this more overtly:

“Oh, for crying out loud,” Raisa said in a deflated tone, then threw her shawl back on and trudged away into the kitchen.

Ha ha, well: not exactly the level of subtlety we’d expect from Babel.

Above, I said that my main criterion in all of this is to ask whether the ending of the story has more bite if they’ have sex or they don’t.

So, next time, I’ll take this up, with some special attention to the ending.

I’d also like to talk a little about the idea of misogyny, in this story and others and, therefore, more broadly, about the way stories accommodate and work with views or ideas readers may find objectionable or fraught.

I find it hard to imagine I’ll be able to cover both of those in one post, ha ha, but stay tuned: we’ll get to this and much more eventually.

Thanks again, and so much, and as always, for being here.

This interpretation also makes the ending hit harder for me. So if we assume they have sex, then in the span of basically a page we have him leaving, so happy he's choosing to swagger and sing instead of walk straight. He gets to the home he shares with his people, opens up is book, and guess what, the author who just inspired this act was actually deeply unwell and died a horrible death. It feels like a kind of ironic, very Babel joke to end on. And since that, and not the sex, is what leaves him feeling brushed by a "foreboding of truth," it feels all the more important.

I loved reading this. Thank you, George! I feel I've just been taken through a lawyer's closing arguments. Guilty of having sex! Yes! I won't write about your question here ("...to ask whether the ending of the story has more bite if they have sex or they don’t") since you'll be writing about the ending next week. I had been wondering if Babel purposely left the sex out of the story--or if he knew just how ambiguous he'd made things. I'm guessing he did NOT mean to confuse his readers. So perhaps it's the translation aspect, or perhaps it's our modern-day minds getting in the way. Because it seems clear that Babel did not mean to confuse us.

For we who are writers, I think this remark by you is something crucial to remember: "a short story is a beautifully tuned, organic system in which every element is humming and resonating and in touch with every other element." This is, of course, how the "gun in the first act must go off in the third act" maxim came into being. Everything in a short story is there for a reason, and every part speaks to every other part. Always good to be reminded of this.

One tiny bit of the story that I loved: In the very beginning of the story, the narrator writes of spending his days visiting morgues and police stations. He says he and his comrades live in dire poverty. And then, he writes, "But the happiest of all was Kazantsev." Leaving behind the part about Kazantsev having found a home in a country he'd never been, the line strikes me as important because of that word "but." It means the narrator, poor and hungry, was happy! He had his passions, his loves, his convictions, and he was happy. This, then, speaks to the end of the story--but i said i wouldn't write about that now, so I'll stop. (I just love that very important "but"!!!)