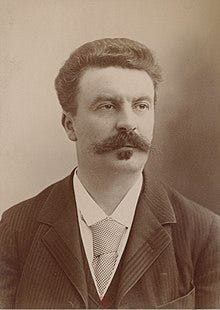

So, last week, I “passed out” Isaac Babel’s story “Guy de Maupassant,” in the McDuff translation. Here it is again, just in case you missed it:

I’d like to try an exercise we’ve done here before, that mimics an approach I use in class.

The idea is simply that, in teaching, a good first move is to first see where the class is.

What appealed to them, what confused them, how are they inclined to approach the piece? What impressions were they left with?

I’ll usually have prepared some notes, on points that I think are important. But I’ve found that these thoughts tend to “land” better in response to some question or concern that emanates directly from the class.

I’ll stand at the board and record the class’s thoughts and queries for the first twenty minutes of class or so.

And then we’ll start working through the list together.

So, I want to ask for your first impressions, and what I really mean is: “What, on first read, struck you?”

This can be something you loved, or something that you felt baffled by; it can be something, even, that mildly offended you. It can be a phrase or reference you didn’t understand. It can come in the form: “Why did Babel do this?” Or: “What was the significance of that?”

Literally: anything that leapt out at you is fair game.

A story, in order to be completed, has to, in its early pages, commit some excesses. It has to draw attention to some aspect(s) of itself; these are often what the meaning is made of.

We can start to notice these by watching what our minds did as we read the story the first time.

There are no wrong answers here: you noticed what you noticed. And, if this is a good story, Babel will have, in a sense, noticed what you noticed; that is, he intended you to notice those excesses.

In fact, my hunch as to how stories work, is that the writer, in the heat of the moment of writing, created/unearthed these excesses and then noticed them himself, and adjusted the story accordingly, during revision, as, of course, he would. (If, early in the story, we learn that Bill is exceptionally tall, the writer has to remember that, whenever Bill is about to pass through a doorway.)

That is, the writer created the excesses out of a sense of immersion in the material, or joy, or fun, or verisimilitude, and then allowed the excesses (kept them in there and honored them) and they, in turn, informed the path of the story.

In the last Babel story we read, “In the Basement,” it was stated early that the narrator was a big reader. This, having been introduced, was not forgotten, and the story grew into that idea, and became a beautiful meditation on the value and dangers of wild storytelling.

Anyway, I’m getting ahead of things.

So:

What did you notice? What questions might you have?

This week, I’ll read all of your Comments and structure my first response (for next week) accordingly.

Also, David Bookbinder was kind enough to supply us with this alternate translation, by Peter Considine.

Thanks, David.

Oh, and another thank you, to The Atlantic, for including Lincoln in the Bardo on this list of “The Great American Novels.” I’m providing this link, for, of course, out of ego/pride, but also because it would make a pretty great reading list.

But mostly because of ego/pride. :)

What is the profound truth that the young artist who is talented, and even the old artist who is not (Raisa) discover and live out in the seduction of their literary translation? That art is everything? That life is finite? That there is miserable war in France and Russia, and everywhere, then and today. That in the end, no matter how talented you are, even if you are the young Guy de Maupassant, whom Raisa claims is everything to her, you still eat shit and die? It is an amazing story in so few pages about youth and art and mortality. It took my breath away...made me happy and sad and desperate and gleeful all at the same time. What a story. I guess the feelings stand out because I write my own stories with an eye toward the ending, always asking the same question: "What from this story do I want the reader to feel?" Babel's target feeling is so much grander and deeper than I ever really manage. Nice. Thanks for the read.

I have to say that, unfortunately and a little bit ashamed of myself for picking this out of all the great proses of Babel, how he wrote about generous/large bosomed women.

It happened quite a few times in the last story and it happened a few times in this story…

Now I’m going to reread Guy de Maupassant and try to find something more profound to say…

But I have to be honest first.