This week I got to return to my old birthplace/stomping grounds, Amarillo, Texas, and give a talk. So, first: a quick thank you to to Chris Hudson, and to the Creative Mind Lecture Series, and the West Texas AMU Distinguished Lecture Series and the Center for the Study of the American West. It was such a beautiful homecoming. So many friends and relatives and nice people I’d never met before, including one older gentleman who asked for my grandparent’s street address, then told me with great certainty that, yes, he’d thought so: He’d been their paperboy from 1952 to 1953.

What a strange moment: this guy, around 75, about the age my grandparents were when they died, referencing a time before I was born, when he was a little kid and my grandparents were younger than I am now.

And time flowed on.

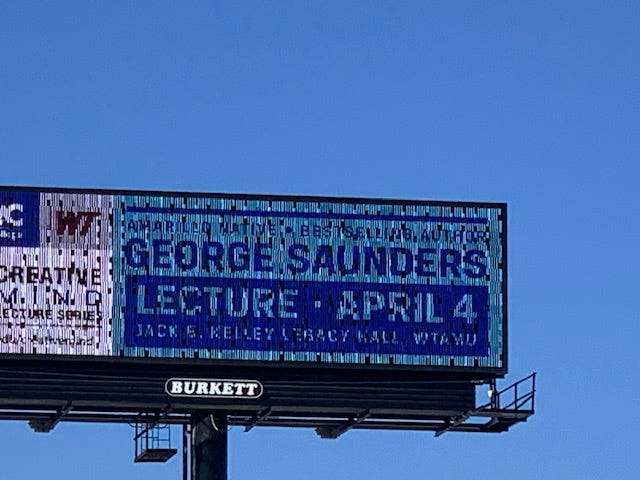

Not only that, I got on a billboard on I-40, which Young Me would have been, as we say in Texas, “just tickled about.”:

And picked up this Amarillo Sod Poodles baseball hat:

So: a very good trip.

And, as always, a crowded auditorium of bright people, not only willing but happy (!) to hear a literary talk, gave me hope.

So, one last session on “Guy de Maupassant,” on the ending, and we’ll move on.

Reading through the comments, I see that many of you have already said some very profound things about it.

So, I think I’ll put aside any explication of the exact meaning of the ending and use this opportunity to talk about the way this ending was set up and, by implication, about the way that endings, generally, are set up.

That is: What do endings do, really? How do we know when a story is done? Is there a method, practically speaking, for “seeking around” for a better ending?

The “best” ending, to my way of thinking, is the one beyond which no new meaning presents itself.

That is: we keep writing as long as the story keeps expanding.

By “expanding,” I mean that the story continues to open up and mean more, in a non-trivial way; the writer isn’t just adding/cataloging new events, but those events are serving some deeper concern the story has put into play.

That is: the story should go on if and only if its continuation is absolutely necessary.

Really, in my work, it’s just a feeling. I’m reading along, approaching what I’ve been assuming for a few days or weeks is THE ending, looking forward to reading it and being elevated (and then triumphantly sending that baby out, and reaping the rewards, yay, yahoo, finally!), but then I read the ending and….something fails to happen.

What I don’t feel is: “YES! I’ve done it!”

Or, to be entirely frank – I might feel a little bit of that, but there’s also something slightly rickety about that feeling, a little overtone whispering: “Nope. You do not want to live and die by this ending, George.”

And one skill I’ve learned over the years is to be able to differentiate a genuine, “YES! I’ve done it!” from a slightly conditional, “YES! I’ve done it!” (One that has, at the end of it, a taste of: “Or have I? Darn: I think I haven’t, quite.”

And when I detect this second feeling, it’s (ugh) back to the drawing board.

But it’s also (hooray) back to the drawing board, because I haven’t sent an undercooked work of art out into the world.

And this – this going-back-to-work-on-the-ending – is a fraught moment.

The natural tendency is to invoke the rational, interpretive part of the mind and try to “figure out” what’s missing.

This is dangerous, though, because the rational mind’s solution tends to be clumsy and on-the-nose; tends to satisfy too well and too neatly.

So, what to do?

Well: outfox the conceptual mind in some way.

Babel has, in his ending to “Guy de Maupassant,” used a technique that I’ve used before and have seen other writers use, and now I am going to make up a name for this “technique,” which is not really a technique at all but really just “a thing I’ve sometimes tried, sort of on accident, and which sometimes, but not always, works.”

But let’s call it Arational Substitution.

To cut to the chase, Babel gets his narrator home, and all the major events of the story have been accomplished. Have all the bowling pins come down, though? Babel apparently felt not.

So, he has his narrator read a book.

He sort of just tacks this riff on to the end of the story. There’s nothing theme-addressing about that, necessarily. It’s not “perfect.” It’s just a thing for the character to do; a chance for the rest of the bowling pins to come down.

He could have, in other words, have him “walk by a shop” or “read an old letter from his mother,” and, the theory goes, the story still could have been beautifully completed.

Just to review, here’s what Babel has very near the ending (in the Considine translation):

Back at home Kazantsev was asleep. He slept sitting up, his haggard legs stretched out in felt boots. The canary down was fluffed up on his head. He had fallen asleep by the stove, hunched over a 1624 edition of Don Quixote. There was a dedication on the title page to the Duke de Broglio. I lay down quietly so as not to wake Kazantsev.

Kazantsev's lips moved, his head lolled forward.

Could we end it right there? (If you have the bandwidth, reread the story, or maybe just the last few pages, and insert this ending, see how it feels.)

To me, it feels truncated. There are important aspects of the story that, with this ending, don’t feel used (and therefore feel extraneous). I’m thinking in particular of the narrator’s earlier assertions about his code for living, and his longing for an adventurous life, both of which have taken up a lot of lines and have offered us a lot of pleasure (and so, in a sense, “are” the story).

So, our desire for a story to be a complete and organic whole is being thwarted.

Bowling pins are still in the air.

At some point, after we’ve been working on a story awhile, it starts to get nicely complicated. It feels meaningful and organized. It has, let’s say, an opinion regarding what it’s about. It has summoned forth a certain complex energy.

That complex energy now wants…to resolve. It wants to go somewhere. It’s like, let’s say, a river gathering behind a dam; it longs for a sluice.

However, that river isn’t just one thing (solid, discrete, simple), but a set of fragile, immensely complicated idea-bubbles, the satisfaction of which is beyond the conceptual mind’s ability to deliver.

So, if we rely on the conceptual mind, the reader is going to get that undesirable, “Oh, right, that’s what I figured,” feeling.

Our Arational Substitution Technique assumes that this complex energy is so intense and well-earned and precisely constituted that it will happily “map out” onto literally anything we put in front of it.

Yes, anything.

What Babel puts in front of his story’s complex energy is a simple vignette: “What if my narrator reads a book when he arrives home?” In doing this, he’s essentially saying, “I want to make a home for that complex energy.”

The complex-energy river goes, “Of course, I’m powerful, I’m sure of myself, I can assert myself anywhere.” And it rushes into the book-reading moment in a way that is surprising and natural and is also (as we’ve seen in the comments) ambiguous, open to interpretation, not too neat, wonderfully rich.

A container is presented and the complex-energy flows into that shape - but still entirely itself (still fully possessed of its essence, we might say).

I had this experience once (that is I, uh, utilized the Arational Substitution Technique) in a story called “The Wavemaker Falters.” I was writing at work in those days and had got to a certain place in the story (not the ending, but the Technique can be applied anywhere) where I just sort of froze up. I could feel that I needed one more burst of action, but what was it to be? It was so important! I was afraid I’d choose the wrong thing. This was dangerous because, writing at work, I tended, when blocked, to stop writing and….well, go back to work. And, while working, I was prone to thinking about my story – and here would come the conceptual mind, simplifying everything into dorkiness.

So, on this one occasion, I had the good sense, when I hit that wall, to jump up and go out to the bathroom, which was located in an atrium outside our office. As I stepped out there, I saw this fit-looking guy wheeling in some big metal contraption, and although that contraption was actually some sort of hot-food transport system, a sentence leapt into my head and I raced back inside and dropped that sentence into the story, right at the place where I was stuck:

“At noon next day a muscleman shows up with four beehives on a dolly.”

And the story moved forward, forming around that incident (infusing it with its energy) and being influenced by it. That beehive does nothing for the story, really, except that, trying to figure out what that guy was doing there, a wedding broke out. That unblocked the blockage and gave the story new life. It didn’t really change the story’s energy; it just gave it a channel to move forward in.

It wasn’t “the perfect” sentence or “the right” sentence – it was just a sentence, just any sentence.

And whatever that story was trying to be about, just kind of went, “Ah, thanks, thanks for the little bridge, now I can proceed to be about what I am going to be about no matter what.”

Let’s say you’re in a really good mood (or a really bad mood). No matter where I put you, that mood is going to get acted upon - it’s going to be “mapper out on to” that environment.

This is like that.

So, Babel decided to have his narrator read a book; that is, he inserted a sort of meta-text into his story (as we’ve seen him do previously in “In the Basement” and earlier in this story, too).

Sometimes, of course, as is the case here, what we “put in front of” that energy isn’t entirely random. We naturally use what’s at-hand (that is, what the story has already coughed up).

We might imagine Babel’s mind working as follows (and likely his mind was “working” simply by “writing;” that is, I don’t think he was actually reasoning everything out, but):

“My narrator is on his way home. When he gets home, what might he find there? Well, his roommate, Kasantsev. What do we know about Kasantsev? He loves Spain. So, let’s have him reading about Spain. It’s late at night. Therefore, let’s have Kasantsev be asleep. Since he’s asleep, the book has fallen open, to the title page. Aha! Let’s let our narrator continue this mirroring he’s been doing with Kasantsev through the whole story, and sit down to read about his obsession (DeMaupassant/ France).”

Then Babel asks (and, of course, “asks” is not quite right – this, too, no doubt, all happened in a quick, intuitive flash) what part of the book the narrator should be reading.

And that pent-up energy finds a landing place (and a “solution”) in the penultimate paragraph:

That night I learned from Edouard de Maynial that Maupassant was born in 1850 to a Norman nobleman and Laure Le Poitteviri, Flaubert's cousin. At twenty-five, he had his first attack of congenital syphilis. He fought the disease with all the potency and vitality he had. In the beginning, he suffered from headaches and bouts of hypochondria. Then the phantom of blindness loomed before him. His eyesight grew weaker. Paranoia, unsociability, and belligerence developed. He struggled with passion, rushed about the Mediterranean on his yacht, fled to Tunis, Morocco, and South America, and wrote unceasingly. Having achieved fame, he cut his throat at the age of forty, bled profusely, but lived. They locked him in a madhouse. He crawled about on all fours and ate his own excrement. The last entry in his sorrowful medical report announces: "Monsieur de Maupassant va s'animaliser (Monsieur de Maupassant is degenerating to an animal state)." He died at the age of forty-two. His mother outlived him.

See how this Arational Substitution has allowed the story to keep opening up, even to this point?

I always think of this as giving the story’s energy a place to play – we’re just providing any old idea or object or interruption. It’s sort of an act of faith. We’re assuming that the story’s energy is so sure of itself that it doesn’t care where it dances; it just needs a place to dance.

George writes: "We’re assuming that the story’s energy is so sure of itself that it doesn’t care where it dances; it just needs a place to dance."

I don’t agree. Or I don’t agree at this moment—I’m very good at completely changing my mind. I think a story’s ending needs exactly the right place to dance, the exact right container. Maybe for some writers of pure genius, anything can be made to work—a resonance will appear no matter what. But for the rest of us… I think Babel very intentionally chose this ending. (I’m actually disappointed that George chose not to discuss it. I really wanted to hear his take on it—on the meaning that George draws from it.) I think Babel knew every element he had written and then chose an ending that speaks to the rest of the story. I think Babel looked at the beginning of the story—at the narrator’s claim to wanting to live a certain life—and then wrote an ending that reflects back on that, as well as reflects back on the entire story. I can’t imagine another ending would work as well (but again, maybe Babel could do it). I don’t think it’s a no-no to use one’s conceptual mind to figure out how to end a story. At a certain point, a writer has decisions to make, plot points to take into account, meaning to discern, pacing to consider, dialogue to cut or expand, vocabulary that needs tweaking—all of this from the conscious mind. Yes, an ending can be written while still working in a dream state. But later—in the revision stage, a writer must awaken to what is on the page. No?

What do we expect from an ending of a story? Why do some story endings disappoint us? Why do we sometimes say, wait—that’s the ending? Why do we sometimes simply sigh and think, wow, perfect ending…? Why do we sometimes feel we’ve been shortchanged? An ending is demanding of its writer. The reader’s expectations are on high alert. You don’t want to disappoint your reader. And so, a writer carefully chooses, paces, lays out the best possible of all endings. It’s not random. It’s not a crapshoot—well, I’ve got three ideas, I’ll take THIS one. It’s a puzzle piece that is carefully set in to make of the story a unified whole.

As often happens here, I wonder if I’m reading all of this wrong. (I’m exhausted today! I drove a friend to a doctor’s appointment and we had to leave at 6:45 a.m. I was up all night worried that my alarm wouldn’t go off…. My brain is a bit tanked at the moment.) Am I missing something?

And can we still talk about the ending that Babel chose? About the meaning of all of it? We have a character who announces himself at the start of the story. The inciting incident—woman needs help with translation. Rising action—each time he visits, he feels the sexual tension rising. Crisis moment—is she asking him to have sex? (Mrs. Robinson, are you seducing me?) Climax—decision made. YES. The sexual encounter occurs. Falling action—he walks home drunkenly, though he’s not drunk. But he’s singing. Oh, life! Denouement—but oh, look! Look how his hero Maupassant died, like an animal. Life is both beautiful and terrible. Live your passions, but know that nothing can save you from life itself!

And so—the ending Babel chose is the best way for that denouement to be revealed. No?

I like George’s idea that an ending is “one beyond which no new meaning presents itself.” In this case, though, I think Babel’s ending is something different: a final twist that he foregrounded earlier. The secret of a good phrasing, our narrator has told us, “rests in a barely perceptible turn. The lever must lie in one’s hand and get warm. It must be turned once, and no more.”

In this case, the barely perceptible turn is the brief mention of the “burning” scars on Raisa’s back, hands, and arms, and the lever is the narrator’s final realization that de Maupassant, the inspiration for Raisa’s passion for the narrator, died of syphilis. Instead of an ending to the story’s meaning, this realization twists a new meaning into the story that the narrator had failed to see all along: the potential tragedy lurking in the reckless, unmoored passions of an arrogant youth.

I came to agree with George’s theory that Raisa and the narrator did the deed when a previous contributor suggested that Raisa might have syphilis. After an image search, I found ample evidence that victims get sores and scars on the backs and hands in the secondary stages of the disease. Which may mean Raisa’s had it for awhile. In Babel’s day, a reader more familiar with the marks of syphilis might have recognized the possible signs more readily than a modern reader.

Now, for me, the thematic resonance between the ending and the story came together. For example, in some ways Babel seems to be correlating the progressive syphilis symptoms described by deM’s doctors in Babel’s final bio to Raisa’s behavior. The “degeneration of the patient to an animalistic state” correlates to Babel’s progressive portrayal of Raisa in increasingly animalistic terms. Eyelashes like reddish fur beneath a moleskin cap. “The neighing of mares” to describe her laughter with her sisters at dinner. And later, when things heat up, Raisa’s body sways like a snake.

Another symptom described by DeM’s doctors is that he “struggled with passion”, wandering from country to country. The narrator is an itinerant pleasure-seeker, an avowed philosophical hedonist who lectures Kasantsev that we are born for only one thing: to find pleasure in working, fighting, and love. Yet, he admits that Kasantsev, who finds a motherland in his love for Spain, is happiest of all. The narrator has no motherland, just a life of random, aimless wandering from pleasure to pleasure to fulfill his overwhelming passions, like poor de Maupassant.

Raisa shares this trajectory, for all she cares about is her passion for de Maupassant, who will be for the lovers, as the narrator tells us, “a beautiful tomb of the human heart.” The erotic stories they read together are seductive, as is the pleasure of drink, and in the heat of things, when Raisa first bares her “burning” scars, the besotted narrator sees it as a sign of passion, not a warning.

This reckless passion is played out against a larger theme: the careless and self-centered hedonism of the lovers juxtaposed against the narrator’s foil: the lovable, generous Kasantsev and his noble attempt at idealism in the face of poverty and hardship — like Don Quixote, the hero of his motherland.

The narrator, also lays into Tolstoy with the typical materialist reduction of faith to fear of death, but is not so cocky after leaving Raisa’s house, his pleasure, the supposed pinnacle of existence having been requited. All that remains for him now is a fevered, Dantesque hell world: vapors, fog, monsters (like the ones painted in Raisa’s trendy Roerichs) seething behind the walls, (will they soon show their faces?) and streets cutting people off at the legs. The kind of thing De Maupassant might have seen on his way to the madhouse.

Kasantsev, though, sleeps happily, dreaming of Don Quixote and his Spanish motherland. When the narrator gets home to Kasantsev, he thinks : a book. A book to put you to sleep like that, to take your mind off the dank fog pressing even now against my very own door.

Something inspiring, perhaps, about the great passions of de Maupassant himself. That’s the ticket.

And then Babel turns the lever.