So, in this, the third and last installment of our “What are we doing here?” pause, and before we leap into the promised, beautiful story by that “under-acknowledged American master,” I want to talk just a bit more about the built-in limitations of our process.

In the previous two posts, we’ve talked about the nebulous relation between analysis and creativity, and about the dangers of becoming addicted to some fixed, permanent method.

Here I want to talk about a third peril, the disappearance of joy in the face of fear.

What are we afraid of, as artists? Well, speaking for myself, I’m afraid of my limitations, and the associated feeling that all this sitting and typing and revising and swearing and making coffee and resolving to do better tomorrow and waking in the night with a solution to my story that, in the morning light, turns out to be idiotic, since there aren’t even any damn penguins in the story, may come to naught, that is, it may come to less than I had hoped it would.

Which, on the one hand, is guaranteed. (I have very high hopes). On the other hand, it’s not guaranteed at all – maybe I will, someday soon, write something that surprises even me, that comes from who knows where, and goes out into the world and surprises other people too, and delights and even consoles them.

That’s the hope and, so, O.K., I’m ready to start, only … wouldn’t it be nice, if I could just be sure that, if I work hard and study craft and revise, revise, revise – if I practice all necessary artistic due diligence – the outcome will be wonderful?

“Ha ha,” says Art. “That’s a good one.”

One question a teacher of writing is often asked, in one form or another is: “Do I have it?” Or, you know, “Do I have it?” That is: “If I keep working at this, will it, in the end, be worth it? Am I a real writer? Will I be able to publish? Can you guarantee, based on what you’ve seen of my writing (of me, my life, my disposition), that this will all work out?”

I completely understand this inclination and had it myself, of course, all those years ago – watched my teachers carefully, in class and at parties, waiting for them to give me the secret signal that, yes, I was, for sure, going to “make it.”

No such signal was forthcoming, because they were good teachers, and knew better.

Speaking from the heart: I have never been able to tell, at all. Honestly. Even among our very gifted students at Syracuse, I would never hazard a guess. There are too many variables and too many unknowns.

As I see it, my job is to maximize a given student’s chances by declining every opportunity I have to pronounce on whether she will or won’t make it – to just avoid that topic altogether.

Like the New York Lottery, my mantra has to be, “Hey, you never know.”

Declining to address this topic is a way of underscoring that she is not predisposed to either success or failure. It is up to her; it depends wholly on what she does from this day forward.

Or, at least, we’re going to mutually pretend that this is the case. We’re going to pretend that all she has to do (per our earlier Robert Frost anecdote) is work, not worry. There is the issue, of course, of talent. But we can’t know the extent of her talent until she’s done the work.

So, for her, the writer, the game is not: “First, satisfy myself that, if I do the work and put in the time, all will be well, and then, well-pleased, go ahead and do the work” but, rather: “Do the work in order to find out.”

Even at this advanced stage of my writing life I still have that inclination, to seek pre-affirmation of success: whenever I start a new story, I wish I could send that (early, partial, crummy) draft to Deborah Treisman, my editor at The New Yorker, so she could email me back to say, “Yes, this will work, for sure – carry on, I promise we’ll run it.” That would really ease my mind. But, in truth, an eased mind is not one that writes good stories. The mind that writes a good story is not eased at all, but anxious and …seeking, let’s say; agitated by the story’s current mediocrity; panicked by the failure of the story to rise to the occasion; discontent with the extent to which the current story is so much like all of those other dull stories out in the world; made restless by the desire to make what is currently derivative original.

What is needed, at that point, is not fear (caution) but joy (daring).

All of this to say: one of the perils of all this talk about craft is that we can fall prey to the fallacy that if we do things correctly, we’ll be doing them beautifully.

We’ve been watching a lot of “The Last Kingdom” around here and there’s a scene (in Season One, Episode Eight, to be exact) in which the hero, Uhtred of Bebbanburg (played by the wonderful Alexander Dreymon), badly outnumbered, vaults himself in over a “shield wall,” among a mob of his enemies and just starts hacking away. He doesn’t first, you know, establish that he’s sure to win. He wants to win, he hopes to win…and, with that vault, he puts himself in a position where he’s going to have to figure out how to win.

That, in my view, is an artist: someone who purposely gets in over her head in a worthy cause, and, once there, to survive, summons forth new resources that even she didn’t know she had, which will later be called her “fresh vision” or “truly original voice” or “mind-blowing comfort with structural experimentation.” She doesn’t know how she’s summoned these resources. Her first skill was the ability to put herself into a position where they were needed.

How does a writer do this? Well, here’s a way to think about it: putting ourselves into a position where we have to wildly improvise is exactly equal to what we’ve been calling “craft.” This, in my experience, is what revising is all about. When we revise, we bring our story, through successive waves of honesty (honest cuts and adds and re-orderings and so on) to a crisis point. We move it past all of its earlier, facile versions. We force it to start asking higher-order questions. (In this model, revising is analogous to the process Uhtred went through that convinced him the only way to win was to leap.) Revision also, importantly, tells us in which direction to leap – it actually constrains the number of possible leap-directions; it has made a tight logical groove in which we may leap, we might say. Over its many successive versions, the story has become more like itself and less like all others. It is not asking all questions, but, suddenly, one very specific question.

Does any of the above help a person learn how to revise? Probably not. I’m describing some of the effects of revision, when done well. (I’m like someone listing the external indicators of a good friendship; the question remains of how one goes about actually having one.)

We’ll be talking more (much more) about revision in future posts, and more practically, I hope, but for now, let’s sit with this idea: revision is a way of gradually forcing ourselves into a position where we have no choice but to be original. We’ve burned through the versions of the story that weren’t asking interesting questions and/or were answering them too simply, to arrive at a place where the story is asking a burning question to which we don’t know the answer (and to which there may, in fact, be no answer).

This is true of the very best stories, I think: they ask, but don’t answer. They ask so precisely that the question morphs into a statement, something along the lines of: “Ah, yes, that’s how it is sometimes in this world.” And there might follow a few second of blessed mental silence.

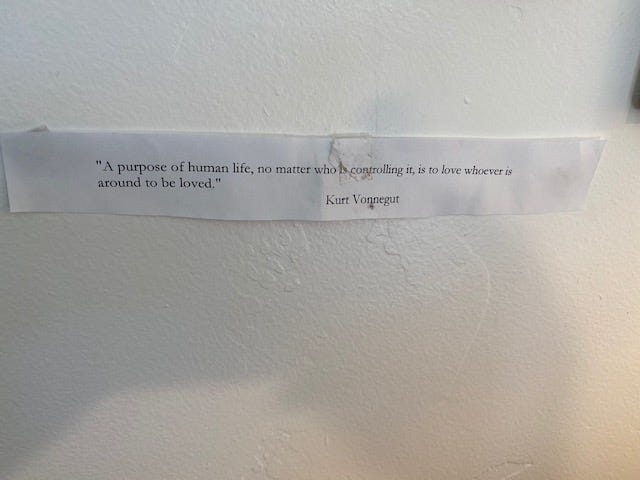

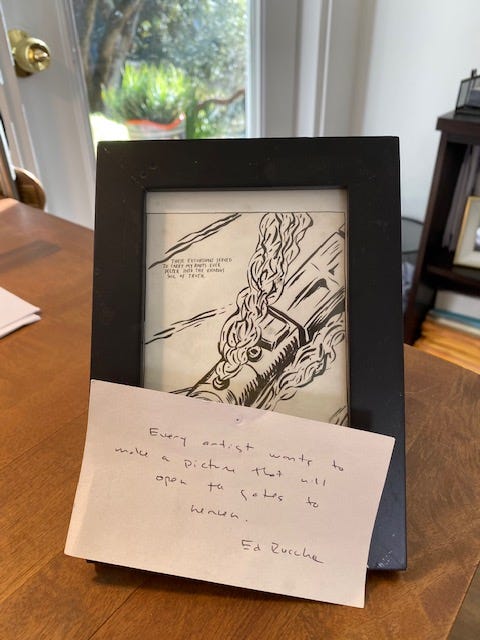

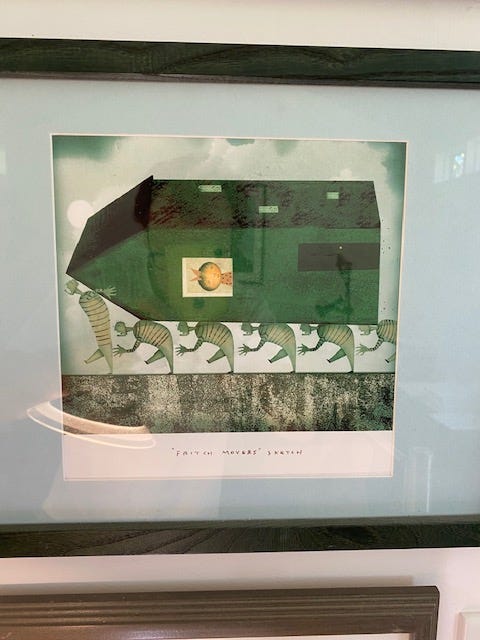

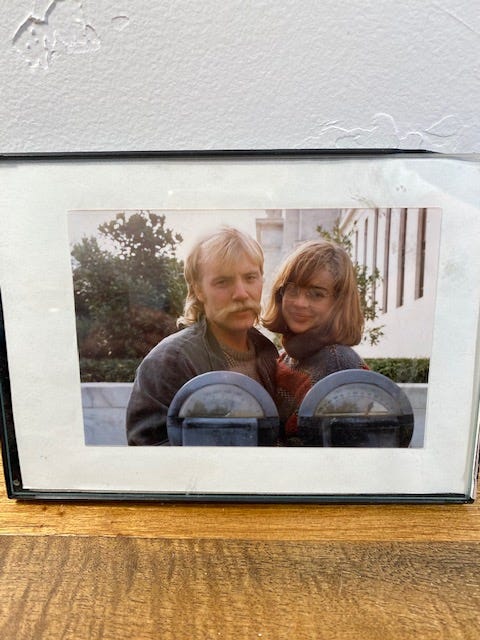

Some of you asked about the Ruscha and Vonnegut quotes I keep near my desk. Here they are, along with a few other artifacts here in the writing shed.

George, I am 73 years old, and was lucky enough to study with Denise Levertov when she taught at MIT and I was an engineering student from Northeastern working there on the coop program. I asked her if I could join her class, even though I was not a student there, and she laughed (a genuine laugh...like a child...as she always did) and then said yes. She taught us what William Carlos Williams had taught her, that a poem was really a machine made of words...and that you needed to fix it, replace the broken part or parts that were broken and not working for a large number of people.

You clearly are as genuine and as generous as she was. Thank you for creating the Story Club. I have only just started two weeks ago, but being here has already opened me up and broken through several writing stumbling blocks in the most marvelous ways.

Such a delight. Thank you all. I want to add that for me, coming to writing late in life has taken “making it” off the table. It’s such a pleasure. I learned (doing visual art) that 1. I was happier when I was working on something and 2. I was really happy when I made something I was proud of. Accolades are great, but not necessary. Old age has got something going for it.