Before we leap in, a quick, happy announcement: Boris Dralyuk, the poet and translator whose version of “My First Goose” we’ve been reading, has very generously provided some magnificent and insightful answers to questions our paid subscribers posed. Those answers will be going out in a post to paid subscribers only, next Thursday, April 21. So, if you’re a free subscriber who’s thinking of making the leap, now might be a good time. Otherwise, free subscribers will be getting their next post the following Sunday, April 24th.

I realize that we’ve been on “My First Goose” for a long time now, and that it’s dire material. I really appreciate your patience. When I love something, I tend to get nerdy about it and it’s made me very happy to find so many of you rising to the occasion.

My plan from here is to finish “My First Goose” off in the next three posts – and then move into a period of doing some (fun) exercises on editing and style.

Then, after that: some happier stories, no violence.

For today: a few more quick thoughts on Pulse 4, which was, you’ll recall: He meets, then abuses, the old woman and her goose (last few lines on 52, first eight grafs on 53).

On page 53, I note and admire that, when the goose must be killed (narratively speaking) it is just killed. Babel doesn’t try very hard to extract sentiment from the action. “For a second I paused, admiring the elegance of the long white neck. Could I do it? Kill such a beautiful creature?” And so on. He just describes the deed: “I caught up with him, bent him to the ground. The goose’s head cracked under my boot, cracked and bled. The white neck lay stretched out in the dung and the wings folded over the dead bird.”

It's brutal and factual and it’s hard not to see it in the mind and believe it.

How are we made to believe in a physical action that we know is invented? One principle that I notice I’ve internalized is to simply make an action happen a little faster than I might have made it in my first pass – to speed it up in the editing.

Consider this:

“Thursday, Ken went to the mall. He moved nervously into the Nordstroms. Looking around, he steeled himself. Over on one counter were the purses. He took a few cautious steps over. The salesperson was across the room on the phone. Should he actually go ahead and steal the purse? For Mom? She’d really loved it, last time they were in here together. The salesperson looked at him, then looked away. He moved closer to the purses. Then he picked up the red one, pretended to be looking for the price, and slipped it under his coat. He looked over to find that the salesperson was still on the phone. What good luck. Maybe this was meant to be. He left the store, heart racing.”

Against this:

“Thursday, Ken went to Nordstroms. The salesperson was across the room on the phone. He slipped the red purse under his coat and left the store.”

In the latter version, he’s stolen the purse before I know what he intends to do. And I like that. It leaves me mystified, surprised, leaning in a bit. (Again, this “speed up action” isn’t a rule. Sometimes, of course, it’s nice to draw things out. An equally valid admonition might be “take your time and be specific.” But, as I say, it’s a little trick that I often find myself trying, almost habitually, when I’m describing an action.

Likewise in the Babel. Before the reader has time to think, “Ah, he’s going to kill that goose, to get the Cossacks to like him, per the quartermaster’s earlier line about messing up a lady” – well, the deed is done. It’s surprising (a surprise that makes sense, after-the-fact), and that is almost always a good thing. That realization washes over me later, delayed even more by the fact that Pulse 5 is then upon me, and I am looking to see what the Cossacks make of the narrator’s action.

I was surprised, this morning, to find that Babel’s 1920 Diary is presented in its entirety in The Complete Works of Isaac Babel, translated by Peter Constantine. Glancing through the introduction, I learn that “the first fifty-four pages of the diary are missing and believed lost.” (That’s a sentence to make the heart sink, eh?) I’d imagine that the source material for “My First Goose,” if it exists, would have been found in those missing pages (since the incident described occurs at the beginning of the narrator’s tour of duty).

Glancing through the Diary – it’s a harrowing read. Very relevant to current events, sadly. Parts felt like they could have been lifted from contemporary diary entries being logged in Ukraine. Much brutality, and also a chance to see the way that Babel (a twenty-something then, always on the move, staying in barns and out in the open) quickly noted things that he meant to come back to later:

“I travel to Rovno in the Thornicroft. Two fallen horses. Smashed bridges, the automobiles on wooden planks, everything creaks, endless line of transport cars, traffic jam, describe the transport carts in front of the broken bridge at noon, horsemen, trucks, two-wheelers with ammunition. One truck drives with crazed speed, even though it is completely falling to pieces, dust.”

I found one place where we can compare the diary prose against the finished prose of the book.

Here’s part of the entry for June 3, 1920:

“Watch crystal, 1,200 rubles. Market. A small Jewish philosopher. An indescribable store: Dickens, brooms, and golden slippers. His philosophy: they all say they’re fighting for the truth yet they all plunder. If only one government at least were good! Wonderful words, his scant beard, we talk, tea and three apple turnovers—7500 rubles.

And here’s a bit from “Gedali,” the seventh story in Red Cavalry:

“Gedali’s store lay hidden among the tightly shut market stalls. Dickens, where was your shadow that evening? In this old junk store you would have found gilded slippers and ship’s ropes, an antique compass and a stuffed eagle, a Winchester hunting rifle with the date “1810” engraved on it, and a broken stewpot.”

And then Gedali goes on to espouse, at length, the ideas telegraphed in Babel’s diary, including this: “And all of us learned men fall to the floor and shout with a single voice, ‘Woe unto us, where is the sweet Revolution?’”

Might be interesting to reflect on the differences between those two texts.

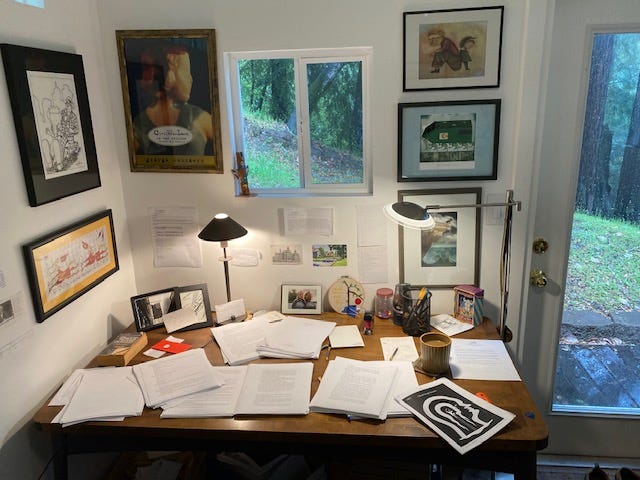

When I was just out of college I worked in the oil fields in Indonesia. I was living in a base camp on Sumatra, deep in the rain forest, about forty minutes by helicopter from the nearest town. At night I’d go back over to the office and try to write, on a big old Royal typewriter we had over there. But I hadn’t really read enough to write interesting stories in those days. In hindsight, the most important writing was happening in my journal, while I was on break and traveling. In there, I was doing that important work of: 1) seeing a thing, then 2) trying to come up with an English sentence that somehow conveyed the essence of the experience of seeing the thing - not merely “accurate",” but somehow alive in its syntax in a way that conveyed a sort of dynamism.

I had the advantage of leisure. Reading Babel’s diary, it seems that many of the entries were written on the fly, just a desperate attempt to get something down on paper before he and the others moved on. As Constantine writes in his introduction, “At times the impressions appear in strings of telegraphic clauses that served Babel as a form of private shorthand.” And yet “when Babel is particularly taken by a scene or situation, he slips into the rich and controlled style that would mark the RED CAVALRY stories.”

I still like to do this now and then, when I see something interesting or new — ask myself: “What would be the best possible sentence to describe this?” And then do the Rubik’s Cube game of trying different versions. This exercise reminds me that sometimes the point is not slavish accuracy, but to get a little life into the sentence - even if I find I am suddenly “describing” something slightly different from what I am seeing, in a sentence that is, for whatever reason, livelier, and would more immediately put an image into a reader’s mind.

Here’s an exercise: set the alarm on your phone for a random time some hours into the future. Forget you did that. When it goes off, write one (1) sentence describing what you happen to be looking at in that moment.

Then revise that sentence a bunch of times.

Speaking of obsessing over sentences…on the personal front, I’m in the very final stages of editing Liberation Day — taking my last look at the manuscript, checking to see if I agree with the edits I made last time, tweaking the text with new fixes and cuts and additions, transcribing those into the pdf of the book, and so on. Also, just to make things interesting, a few days ago, my glasses broke (they just snapped in half one day) and so I am wearing an old pair, with one lens that’s pretty good and a second that was pretty good back in, uh, 2008. But we carry on!

It’s amazing to find that there is always something to improve. I’ve read these stories so many times, and they’ve been edited so well, in some cases by multiple editors, and yet I feel that I’m still finding places to improve them incrementally.

And then will come that sweet moment when I’ll get all the way through one without feeling a need to change anything.

How wonderful it is to get to do work one loves.

Next time, on to Pulse 5.

Oh, and for those of us who celebrate it: Happy Easter.

I love it when Babel writes in his journals “Describe the transport cars in front of the broken bridge at noon.” Will he ever do so? Maybe not. That sentence already tells a story. I’ve read that his journals are full of this same sort of instruction to himself: “Describe _____.” It’s a wonderful shorthand, a way of remembering things, perhaps visually. Not slowing himself down in the moment to add more to what’s already in his head. Or using it as simply a word—his way of getting things down. Taking the pressure off. Moving on and moving through.

Although then he writes this: “An indescribable store: Dickens, brooms and golden slippers.” Later, in the fictionalized version, he describes what he has said is indescribable. I find that….humorous?

Your example of a quick entry/departure (Nordstroms, stolen bag) is a great lesson in understanding when context is or is not necessary. Do we need anything more than the short version? No. As you say, it’s not a rule—sometimes the longer version becomes necessary depending on the voice, the style, tone, etc. But, in story terms, we do not need more context. We get it. To add further exposition, detail, explanation—we risk creating a boring paragraph. Better to get in and get out. (That’s what she said.) (Sometimes.)

I love this sentence: “When I was just out of college, I worked in the oil fields in Indonesia.” My sentence: “When I was just out of college, I worked at The Frankfurter on University Way.” Not as exciting as yours, George, but oh do I have stories (I was fired).

Happy Easter, George, and anyone else who celebrates!

“But I hadn’t really read enough to write interesting stories in those days.” Well, that surprised me a bit. I’ll be thinking about what that means over the coming week.

It actually emboldens me to try a story soon. I remember something Didion wrote about writing. She starts with nothing more than an image, not an idea. She never knew, she said, where the image would take her. I notice moments every day now that could possibly serve as a springboard for such a story. For instance, this past week, I was driving behind an expensive-looking white car in a well-to-do neighborhood in Sacramento. We came to a traffic light. As I waited for the light to change, a woman’s arm with a light blue plastic thing in her hand stretched out the window. The grace of the arm movement and the vivid blue of the object in the sun next to the white car drew my eye and that of a friend in my passenger’s seat. There was a pause before the woman in the car ahead poured liquid out of the plastic thing on to the road. As it rotated in her hand I saw it was a woman’s camping gadget for peeing in the woods. My friend and I looked at each other in astonishment. I said, “Now that is a short story.” My friend, who knows nothing about the Story Club, looked at me as though what I said was even weirder than the little action we both just witnessed.

I loved what you had to say about “Gedali,” one of the stories I liked best in Red Cavalry.

Happy holidays, everyone who reads this!