We’ve been working with the (excellent, musical) translation of “My First Goose,” by Boris Dralyuk. There are also wonderful versions by David McDuff, Val Vinokur, Peter Constantine and (the one I read first) Walter Morison, among many others.

In this post and the next, I’d like us to explore the issue of translation and, therefore, of style.

A translator is a stylist; she takes a sentence that represents a basic reality in one language (“The tall man entered the café, perhaps in pain, with a stoop and an air of hesitancy”) and then has to choose a certain syntax in the second language that somehow conveys the sense and the feeling and sound of the original. But because there is no exact match, she enters into the realm of style.

In my experience, what we call a writer’s voice depends very much on her ear – her way of hearing language and preferring this over that. These choices are idiosyncratic and indefensible. But they are also essential.

Here’s an exercise to help me show you what I mean.

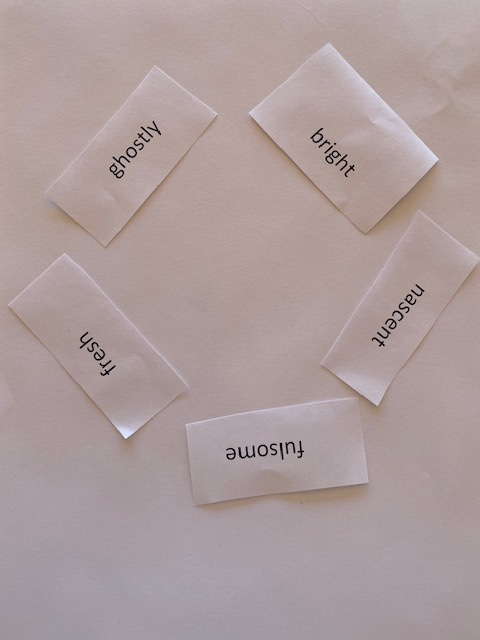

Exercise:

Below are five words. The assignment: put them in the best order. Do this quickly.

Ready? Go.

So, first: what order did you decide on? What order seemed “best,” to you?

Second: How did you decide? That is, what were you drawing upon as you ordered the words? Note that, above, I didn’t give you any guidance on what I meant by “best.” Therefore, you had to supply it.

Whatever your basis was for your ranking, it says something about you as a writer (and as a reader). It says something about your ear. It says something about how you edit (how you feel, and then implement, a preference). Try to recollect what your mind was doing (what state it was in) as you worked to put those words in your preferred order. In what were you trusting? On what were you relying?

Recognize, too, that the explanation of why you chose the way you did is secondary to the fact that you chose - the fact that you could. In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain I talked quite a bit about the idea of “micro-choices,” the accumulation of which add up to one’s voice. This exercise is a way of getting in touch with our own agency, our own (perhaps quiet) preferences - they are there and we don’t have to name or justify them - we just have to know how to get to them when we need them.

When I do this exercise, I feel my mind snap into the same mode it goes into while editing. (Should my sentence be, “Larry was a tall man with a pronounced stoop and he walked into the restaurant seemingly in pain,” or “Seemingly in pain, Larry, a tall man with a pronounced stoop, walked into the restaurant,” or “Tall Larry walked stoopingly into the restaurant,” or “Larry, stooping, tall, in pain, entered?” And on and on, ad infinitum: that Rubik’s Cube in the brain turning and turning.)

You can try this with any random five words, or you can go into an existing manuscript of yours, pluck out a random sentence, and spend a week or so producing one new incarnation a day. This might be seen as a practice of exploring sentence varietals.

A related idea: we each contain many voices and the one currently manifesting in a sentence is not, at all, the only we have access to. We tend to phrase things a certain way the first time - and sometimes it’s just right. But I think it’s good to think that, if we come back at it again, that’s a “first time” too. (It’s, you know, a “second first time.”) Both come from us. (We are vast, we contain multitudes.)

Next post I have another translation-related exercise for us to try, and after that we’ll take up Pulse #3.

nascent, fresh, bright, fulsome, ghostly...the evolution of a flower?

Thank you for focusing on the important creative work of translators. We are too often overlooked.

I just read a book review of a recent Eng translation of a novel, and the name of the publishing co was mentioned but the name of the translator was not. 🙄

And then I read this post and felt better. Looking forward to the next post too.

Cheers from Athens