As mentioned last time, let’s stay on Pulse 3 for one more post.

It’s sometimes useful to think of a pulse as being made of sub-pulses. Pulse 3, you’ll recall, was: The Cossacks torment the narrator (i.e., don’t accept him).

So, how, in “My First Goose,” is this idea of “being tormented” embodied? Well, it’s embodied via a series of simple actions:

Lad throws trunk over gate.

Lad farts at narrator, walks off when done.

Narrator puts his trunk back together.

Narrator retreats to a corner of the yard.

Narrator notices some cooking going on.

Narrator recalls home, feels hungry and lonely.

Narrator lies down to read.

The Cossacks come over, step on his legs, make fun of him.

Narrator can’t concentrate on his reading.

And then this causes…the next pulse, Pulse 4, in which he takes action in response to all of this tormenting.

As you know by now, one of my litanies is that an important part of “craft” is to find a way to think about your work that doesn’t drive you nuts, i.e., that lessens the associated anxiety and pre-worrying we all tend to do. This is important because everything important happens when we are happily or somewhat happily lost in the process and working intuitively.

One thing that assuages my anxiety is the thought that a story, even the most complex story, consists of a series of relatively simple actions. We have to be made to believe in the reality of these actions, yes, and that’s no mean feat. But once we do, the meaning of the story will naturally arise from the juxtaposition of these simple actions – the way one is perceived to cause, or relate to, the next.

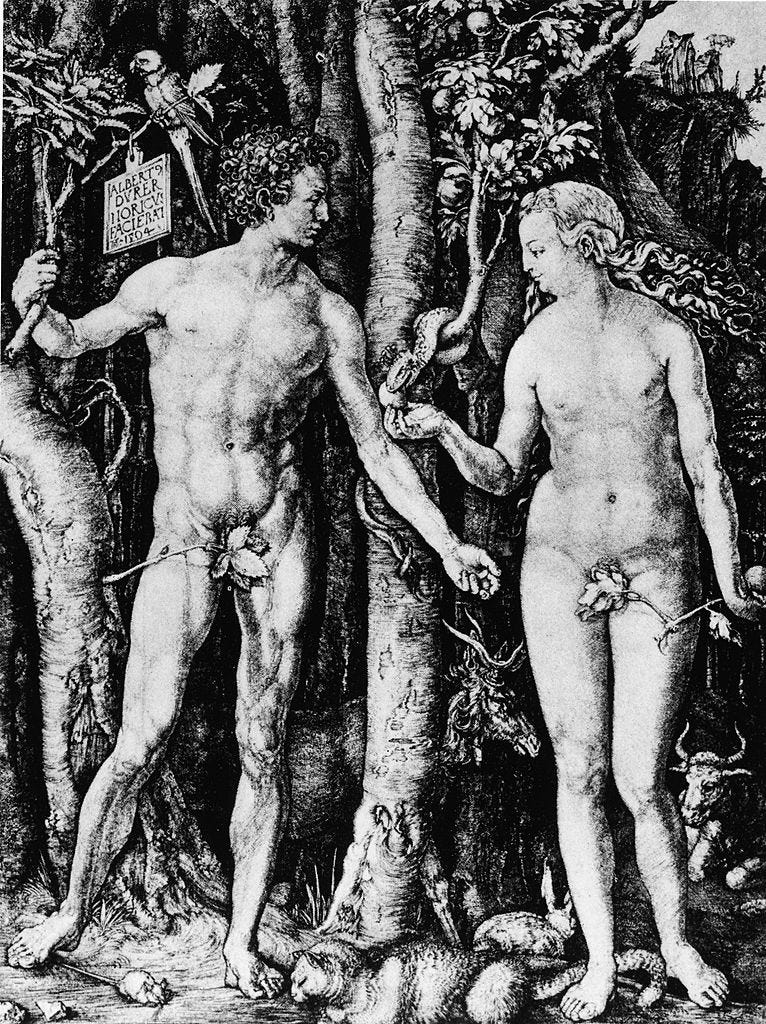

You know: God makes Adam and Eve. God tells them not eat the forbidden fruit. Influenced by the devil, they do it anyway. God expels them from Eden.

There are abundant themes and meanings and resonances in that simple tale, of course, but they come naturally out of that exact sequence of actions.

I’ll sometimes do this with a story in-progress – just reduce a section to the simple actions within it, shorn of any related or aspirational meanings or themes.

The way in which a story means has so much to do with just this simple thing: what happens, in what order.

Consider, for example, the following beats:

A man watches a parade go by.

The man weeps.

The man energetically sweeps his kitchen.

In this order, it means something like, “A parade makes a man sad and then, recovering, or trying to, he does some work around the house.”

Then consider this:

A man energetically sweeps his kitchen.

The man watches a parade go by.

The man weeps.

This is different: He’s doing fine, but then the parade goes by and, for some reason, wrecks him.

Or this:

A man weeps.

A parade goes by.

The man energetically sweeps his kitchen.

This is: a sad man is consoled and uplifted by a passing parade.

So: three very different pulses, three very different men. And the three stories that might follow these pulses will also be very different.

Once we have the events in a certain order, we can lean in, asking, for example, re the third ordering above: What is it that uplifts him about that parade? Or, re the second ordering: what is it that disturbs him about it?

This is where we move into the realm of character. What sort of man is he, to be uplifted or depressed by a parade? And to find out, we get to (have to) decide on the details of the parade. If it is a procession of elderly World War II vets that uplifts him, that’s one story. If it’s a violent demonstration against a certain group of people that uplifts him, well, that’s another story. If it’s an Easter parade, again: a different story altogether - and a different man.

We might say that the ordering of events implies a certain causality, which then opens up the door for us to go in and make character. When Adam and Eve, told by God not to eat that fruit, do it anyway - that signals “disobedience.” When we know that they were persuaded by the devil, we might ask, “Well, how did Satan persuade them?” There might be a version of the story where Satan talks about how beautiful and perfect Adam and Eve are - that version would be about, say, “disobedience caused by pride.” There might be a version where Satan promises them great riches - that version would be about “disobedience caused by greed.” And so on.

Once we settle on our order, that also tells us what may want to happen later in the story. The first example above (“A parade makes a man sad and then, recovering, or trying to, he does some work around the house”) might create an expectation that whatever made him sad about the parade is going to keep making him sad over the course of the rest of the story, and our expectation of escalation may require that his sadness reappear later in a more formidable, less easily deflected, form. Let’s say the parade reminded him of his deceased son, who died in a war. Well, in this pulse, a military parade reminds him of his son, but he manages to push his grief away. But his grief is still with him, and we wait for this issue of unassuaged grief to reappear. We wait to see what that grief causes him to do when he can’t so easily push it aside.

So, a story is a series of simple events, ordered in such a way as to bring forth meaning. Our skill as writers might be said to consist of (somehow) inventing those actions in the first place, then ordering (or re-ordering) them in the way that causes the most light (or sparks, or energy, or whatever) to be given off.

Another way of saying this: we are trying to land on the order that makes the story its most considerable self: the version of itself that raises the deepest questions. With me, there’s sometimes this feeling: I am steering toward certain questions, rather confidently, because I basically know the answers to them- and then the story swerves off and makes me ask a question I don’t have an answer for. And that’s a good sign, very good - and sometimes the story poses that question unprompted, via some reordering of its primary events, a re-ordering that I, by now, tend to attempt almost automatically, without realizing I’m doing it, like a person habitually futzing with a Rubik’s Cube.

So, the first exercise here might be to put each of the events listed above, for Pulse 4, on an index card and…goof around with them a little. Reorder them, absorbing the meaning that comes off of each arrangement. Eliminate one or more from the ordering, see what that does.

When I’m playing around in this way, I’m looking for those quick little spontaneous, unsolicited reactions that arise, like: “Oh, ha, yes, that means more.” Or: “Of course, this is richer than that.” There’s very little reductive or analytical thought going on. It’s a delight-seeking process. I’m not trying to be delighted - I’m waiting for some delight to occur, on its own. And, just to be clear, it’s not huge delight. It’s just (if I’m using this word correctly) a frisson of delight.

Here are those subpulses again, for ease of reference (after this lively painting of some Cossacks circa 1890):

Subpulse Reprise:

Lad throws trunk over gate.

Lad farts at narrator, walks off when done.

Narrator puts his trunk back together.

Narrator retreats to a corner of the yard.

Narrator notices some cooking going on.

Narrator recalls home, feels hungry and lonely.

Narrator lies down to read.

The Cossacks come over, step on his legs, make fun of him.

Narrator can’t concentrate on his reading.

Working with these on index cards in this way may help you get a feeling for how smart Babel’s attention to cause-and-effect is, how deliberate, how propulsive, how much one subpulse fuels the next one/is in relation to it.

Here’s something I haven’t tried to write about before so forgive me if it’s a little vague. But when I’m thinking about the ordering of events, I often find myself paying attention to, or hoping for, certain connective or relational terms - terms like AND THEREFORE or BUT NEVERTHELESS or WHICH THEN CAUSES…

When these start appearing, it’s a sign of strengthening causality.

So, for example: Here, our narrator smells the Cossacks’ cooking WHICH CAUSES HIM TO feels hungry and lonely AND SO he sits down to read.

An exaggerated example:

“Tom was feeling bored AND SO he bought a Ferrari AND BECAUSE he was broke, THIS CREATED additional stress in his life AND SO he ran off with the circus.”

Or:

“Cindy, who craves warmth, is advised to break up with Tom, who is a terrible communicator, BUT SINCE she loves him deeply BECAUSE OF his awesome juggling skills, she NEVERTHELESS stays with him, until the fateful day he joins the circus, IN RESPONSE TO WHICH she, rashly, burns down the whole circus, WHICH CAUSES HER to enter a nunnery.”

We might also sense the way Pulse 4 grew organically; once the trunk has been thrown over the gate, there’s the possibility that it may fall open; once it does fall open, the narrator has a reason to crawl along the ground (indicating abasement). This abasement, maybe, causes him to retreat to the “far end of the yard.” This retreat means that the Cossacks have to cross that yard to later torment him further, which we feel as an escalation. It also means he’s cornered: he’s done his best to hide and now there’s nowhere else for him to go.

All of this is tied up in the way Babel has ordered these events.

In my reading of the story, the ordering makes me feel that “the Cossacks torment the narrator” has been fully and cleverly used. I don’t need more torment. I am convinced – that the torment is scary and that he is at the end of his rope. And then I am happy (and relieved) when I feel the next pulse coming on, and feel the possibility that, in that pulse, he will take some initiative to protect himself.

The pulse we called “the Cossacks torment the narrator” has been broken down into a series of small actions, and, by the choosing involve there, has been made utterly convincing.

A second possible exercise here: take a story of yours and go through it, listing the simple actions. What qualifies as a “simple action?” Well, good question. For me, it has something to do with the verbs - if we look at the list of subpulses, we find: throws, farts, walks off, puts his trunk back together, retreats, notices, etc. This process is not interested in rationale but action. Someone leaves town, someone slams a door, the slammed door is heard by someone else, who does something in response. That sort of thing.

Or…sometimes I try to imagine a scene the way it would be done in a silent movie: Where are we at the beginning of the scene and where are we at the end, and what were the steps along the way? What did we see? (Watching some Chaplin is always helpful when trying to get into this mindset.)

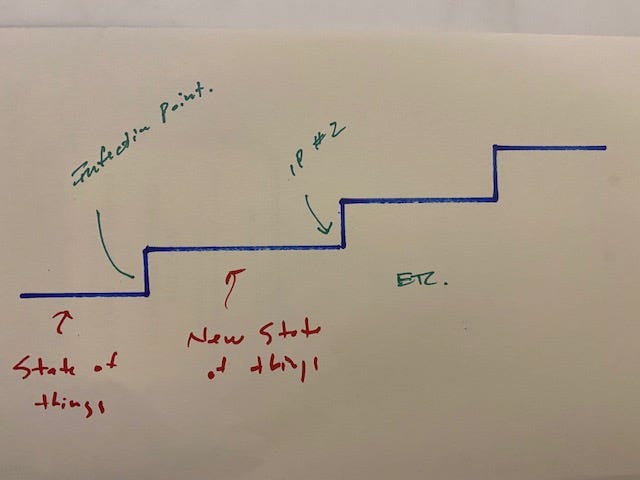

Related to this, I sometimes might think in terms of inflection points. If we think of a scene as a line graph, with the passing pages along the horizontal axis and Dramatic Energy along the vertical, where does the line jump up? At what points does the fundamental reality of the scene shift?

I’ll confess, too, to a bit of bias - I like it best when the State of Things changes because someone has done something. (It’s all well and good if Henry loves Tim. But I believe it when Henry buys Tim the car he’s always wanted. The love, in this way, gets embodied and proven.)

Can “thinking” be an action? Sure. I have a lot of thinking in my stories. But one of the ways a swath of thinking “earns its way in” (in my esthetic) is that it causes something. I also find myself liking it best when a swath of thinking is naturally caused by something - a man walks by another man who is helping along an elderly lady and this causes him to think of his own mother.

But, of course, all of that is just about me, about my approach. We each construct our own internal system of preferences and rules and so on…

OK – by now I know that I don’t have to do much here to elicit some world-class musing from all of you. So, I’ll just stop here and let you have at it.

And we’ll take up Pulse 4 next time: He meets, then abuses, the old woman and her goose (last few lines on 52, first eight grafs on 53).

Thought my fellow story-clubbers might get a kick out of my adaptation of "My First Goose" into comics form: https://thequixotesyndrome.com/blog/my-first-goose/

George, it’s been great reading your dissection of these pulses to see what essential work each story element does and all the hard decision-making that goes into it— something I was acutely aware of while converting MFG into the constraints of a 6-tiered, 2-page comic. It required a certain degree of ruthlessness and reimagining, which made me appreciate Babel’s genius all the more. Thanks for the great club!

You know what’s so great? How much I grow to love each of our Story Club stories.

Even if after first read I’m like, “meh,” by the second post my affection grows, and continues to grow until each story has become an old friend with a rich, personal history I can fondly recall.

That really makes me happy.