Q.

Dear George,

How does an artist move beyond sentimentality? After six years writing and never completing anything (everything was too weak to bother driving home), in the past year I’ve finally started to be able to finish a thing. I try my hardest. I leave everything in a piece I complete, revising revising revising until I can honestly say “This is the best I am currently capable of.” That’s a gratifying place to take something, whatever the world’s reaction.

My work isn’t yet good enough for me, though. I get approving feedback from friends, have felt confident enough to submit work and bear rejection, but still, when it’s just me across from the page, what has come out is not yet art. It’s too neat, well-explained, and ‘just so’ — or ironic and cynical in an attempt to move past these limitations. I don’t want that. I want to be able to create art. But I grew up in Middle America, anaesthetized by the cheap comforts of rerun sitcoms and Disney movies and superficial relationships where everyone is precisely this: ‘just so,’ a good son, friend, student who plays their assigned role exceedingly well. I was a good son. My parents bought me nice clothes, I sang along to “The Sound of Music,” and deer would come to graze in my backyard while cardinals and blue jays and robins sang. Everything had a highly probable course. I was in complete despair, but when I write, that complexity separates out into good and evil, black and white. Everything takes on its assigned role. I end up with work that’s flat — very Hollywood, very television, very middlebrow (and that’s generous).

But what inspires me is Thomas Mann. Richard Wagner. William Faulkner. Elsa Morante. I like Aeschylus, Dante, Caravaggio. Federico Fellini. Job, or the book of Isaiah. Edna O’Brien. Hermann Hesse. Milton. Artists who create work that replicates the full truth, pain, and beauty of being alive. Courses are not completely probable. People act in strange ways. I want Milton’s Satan, not Disney’s Aladdin. La dolce vita, not Roman Holiday.

Even where these artists move into pathos (I’m thinking particularly of the endings to Mann’s Death in Venice, Morante’s History, Hesse’s Siddhartha, Faulkner’s “Red Leaves”), it’s somehow earned.

Take Death in Venice. Once Mann establishes the plot, anyone can guess from the title that Aschenbach will die contemplating this beautiful boy on the beach. But when the punch comes, it hits, and at an unexpected angle. It’s real. But when I attempt anything similar, the plot sounds like a Hallmark movie in my head, and the writing has that inflated mediocre quality of a petty-bourgeoise try-hard. That’s not good enough for me. That’s not my ambition. I want more, but I can’t yet do more. Grrr.

I ask this because I know you have high ambitions for your art, too. And I know you sometimes skirt the sentimental in your work. It must be a problem you consider and struggle with. Lincoln in the Bardo had great depth. A story like “Sticks,” too, with such nice ambiguity — Chekhovian. But when I think of a story like the “Tenth of December,” “suicidal man with cancer saves fat bullied kid” would be the kind of plot I’d resent myself for considering. It is sentimental. But you do turn it into something in which someone gains something of value. How?

I write so slowly. Projects take time. So much time. I revise and revise and revise, but where’s the depth? Where’s the energy? Where’s the spirit that should be seeping up through the gaps between the letters and words? My taste doesn’t translate into prose. So how does someone let go of the neatness, the ‘just so’ quality, the need to be understood? How does someone create space for ambiguity, for truth and power?

How do I leave the false but comfortable behind? There’s a question of technique here, sure; but even more so, a question of mentality. When you were raised to live like a bourgeois, how do you start to think like a demigod?

Thanks for Story Club and for sharing your work with the world.

A.

This is a deep one – I can feel the passion and the frustration and the admirable ambition behind the question. So, thanks for the open, frank spirit here.

I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating: there’s a line beyond which we should be cautious about giving writing advice. Without reading some of the work in question, we’re really driving blind.

The truth is, if I could read your work – if I had time and enough bandwidth to do so – I’d likely answer this question simply by way of line edits. Honestly: all big conceptual questions “reduce to” the deletion or compression or reimagination of specific lines in the work at-hand.

This feeling of roteness, or non-depth, or sentimentality you describe: it shows up, no doubt, at certain places in your text. (You’re reading along, it isn’t disappointing….and then it is.)

Where does that happen? At which line? What might you do about it?

That’s the way these kinds of questions are best answered, really – putting aside the concepts and looking closely at the lines.

That said, let me make a few general observations, in the hope that one of them might hit home for you, dear Questioner.

First, on the issue of sentimentality.

I try to make a distinction between “sentimental” and “emotion-rich.”

“Sentimental,” we don’t want.

“Emotion-rich,” we can’t live without.

“Sentimental” (in my lexicon) means: “trying to claim unearned emotion.” So, a mere idea can’t really be “sentimental.” It can, however, be “potentially sentimental.”

And then the writer’s job is to avoid sentimentality – to earn the emotion inherent in the situation.

And this is a craft issue.

This is what I was doing every day, while writing “Tenth of December”: saying, to myself, “Yes, this could slide off into the sentimental if I’m not careful.” And then I was trying to…be careful. Trying to eliminate the sentimentality, while retaining the (genuine, earned) emotion.

When a person is dying, like the guy in that story — he has emotion. When a kid is bullied, he has emotion. But there are the emotions one would actually have in those situations (good) and the cheap shortcuts a writer, including me, will feel inclined to fake along the way (bad).

Discerning the earned emotion from the faked - that’s hard, line-by-line work.

So: sentimentality (or any defect, really) is going to rear its ugly head at specific places in the text.

Can you find those places? (Hint: it’s wherever your reading energy drops.)

You ask, paraphrasing Flaubert: “When you were raised to live like a bourgeois, how do you start to think like a demigod?”

Per the ideas above, I don’t feel that we have to worry too much about how we were raised (too bourgeois, too comfortable; not bourgeois enough, in a too-hectic household, etc.)

I’ve always found it fruitless to try to relate the way I write to, for example, my childhood, or any of that. I’m sure there are all sorts of interesting relations, but I don’t know how to use these to make my writing better.

The only way I have found to make my writing better is to read it, and then change the things I don’t like into things I like a little better.

Everything gets accounted for in that process.

Also, it keeps things simple and keeps my anxiety about this whole writing thing at bay.

There’s a pattern with which I’ve become familiar in these twenty-five plus years of taking questions about process: the questioner will often embed an assumption that may (may!) be part of the questioner’s issue.

Here, I’m drawn to the assumption that growing up in a functional household is somehow causing your work to be “flat — very Hollywood, very television, very middlebrow.”

I’d like to challenge that idea.

What if it didn’t matter where a writer came from? What if it’s not the life that makes the writing?

Or, to be more exact: what if, wherever we came from, that fact could be used to our advantage?

I think, for example, of Tolstoy, who had, according to him (and to the three novels he wrote about these periods of his life, Boyhood, Childhood, and Youth) a happy, safe, privileged, upbringing. But his work! He gets everything in there. All manner of darkness and light, and celebration, and cynicism: everything. And I’d say that part of the reason he is such a capacious narrator is exactly the security of his upbringing – he used that confidence, one feels, to make his (vast) novels.

Or, on the other hand, we could bring up any number of writers who came from difficult, even traumatic, childhoods, and used that in their work – in their subject but also in their style. (I think here, for example, of Dorothy Allison.)

Whatever happened to a person, good or bad, is going to show up in the lines, and then the goal is to work with the energy of that in order to bring that quality fully forward.

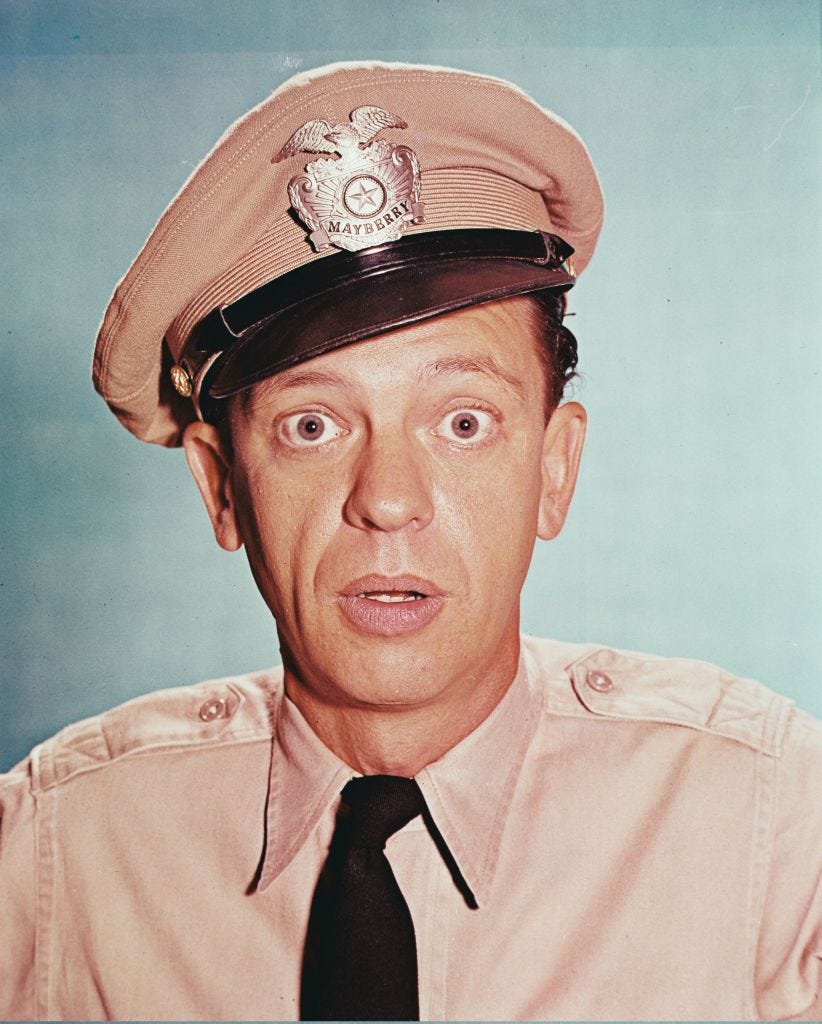

In this context, oddly, I think of Don Knotts, whose portrayal of Barney Fife was great because, I think, Fife was present in Knotts, at trace levels, and Knotts somehow sensed this and lured Fife out.

Maybe, being an artist isn’t about transforming ourselves into some totally new and foreign being, but finding out what sort of being we are, and being more of that.

In this model, we don’t think, “If only my childhood had been the perfect one for a writer,” but, “My childhood, any childhood, is, by definition, the perfect one for a writer. Now: which writing did my childhood perfectly prepare me to do?”

And, again: we don’t have to “decide” this - we have to seek the answer, by observing the power, or lack thereof, in our lines.

I notice that, in your question, dear Questioner, just after saying that your parents bought you nice clothes, and that you sang along to ‘The Sound of Music,’ and deer would come to graze in your backyard, you say: “I was in complete despair.”

If I was your teacher, I’d ask, in our conference: “About what were you in despair? What was the quality of that despair? Are you getting that feeling of despair into your work? Can you break ‘despair’ into more specific descriptors? Can you demonstrate that despair in an action or a scene?”

Because that, right there – the contrast between those grazing deer and that kid’s despair – is pretty interesting. (All of life is there, potentially).

My dear friend, Mary Karr, does an exercise in her memoir classes in which she encourages her students to gradually imagine their way back into some moment of their past, by engaging the senses, one after the other. I tried this once, when we were co-teaching, and it was really something. (The last step, as I remember it, is to ask yourself, “What did I want?” )

The effect was to underscore the distance between “the way I think about my childhood” and “the way a moment of my childhood actually felt.”

The former is a concept, one that we tend to tidy up over time.

The latter is what we might actually use in a work of fiction: that complex, three-dimensional, nuanced, contradictory moment, in which everything remains open.

If we wanted to as you so nicely put it, “replicate the full truth, pain, and beauty of being alive,” I’d think we’d want to be constantly trying to get back in touch with that “how things actually felt.”

I’ll bet that if you, dear Questioner, go back to your childhood, via the Mary Karr method, odds are, you’ll find some tension, some stressors – you hint at this with “I was in complete misery.” I don’t mean you’ll necessarily find hidden trauma. But you’ll find that your mind was a particular human mind, set down in a particular milieu – and there was motion in that mind. There was pressure. There were conflicting desires, upwellings of shame, bemusement, confusion– all of that good stuff.

Even a person raised alone, fed by a machine, out in a cave somewhere, exists in this atmosphere of pressure – because that pressure is intrinsic to the human mind. The mind makes the pressure, the tension, the longing, the hope.

We want this thing, we get it…and then we want more. We always feel slightly off, somehow. We find ourselves at peace but not the right kind of peace.

And so on.

This is what drama is, really: it comes out of the truth that nothing is ever enough for us, that every human situation (even a quiet one, even a happy one, even a deeply contented one) always teeters on the brink of change, because of the restlessness of the mind.

And that right there is the stuff of literature.

I remember feeling the way you describe – that my life was too dull or functional to ever produce good writing. I was too happy! I liked being alive too much! I’d write something, find it lacking, and think: “If only something dark or terrible had happened to me, I’d have something more interesting to say.” (“If only I’d been in a war zone, or belonged to a crime family, or something.”)

But over the years, this changed. I started working for a living and had a lovely family and found myself working a corporate job about which I could summon up absolutely no feeling of glamor – and yet life went on, and my job was, in its strange way, interesting, and I could find pleasure in aspects of it, and it started to become important to me, and I got all bound up in the rivalries and little dramas (all of that human stuff) and I gradually started to realize that anywhere two or more people were gathered…even an obscure corporate office…there was literature. (There had to be; what else was literature, but “what happens when people gather?” And even (see “cave example,” above) if there was just ONE person present…)

Or at least this was an assumption I started making, one that helped me proceed.

There’s a move I sometimes do: say there are two people sitting on a bus bench, talking. If I look at them closely, I can start to detect some tension. Some difference between them. Some quality of negotiation. Some fondness, in a specific flavor.

And whatever that is, writ large, is what we might call political. It’s out there, in that larger form, in the world, causing grand political and moral-ethical problems.

By this definition, there’s no life, no moment, that doesn’t have the big themes in it, if only we look closely enough.

Each life is just a tiny slice through the great all-that-is.

Our stories are not going to be vast because we have known and done and experienced everything.

But they might become more vast if we assume that (step one): everything you’ve ever felt, even if that feeling has faded from your life, is being felt by someone, somewhere. (Someone, somewhere, is having as much bad luck as you ever had. And as much good luck. Someone has just fallen in love hard for the first time, the way you did; someone is experiencing a level of despair exactly equal to the greatest despair you’ve ever felt, and someone may even be feeling, poor dear, even more despair than you ever did.)

That is: it’s all still out there. The world is always vaster than we can imagine.

“Process,” so-called, then, is the activity of trying to get outside of our bounded minds, and artificially induce in the reader the illusion of this vastness.

If we want to, as you put it, “create work that replicates the full truth, pain, and beauty of being alive,” we have to actively expand our view, by continually asking ourselves, “What else is happening, out there beyond my perception and experience?”

We can start by a self-directed version of that bench-bus exercise: assume that whatever is in your mind and heart is 100 percent valid. “I am a human being. If I’m feeling this, it’s interesting, it’s a valid topic for literature.” We try to believe that in even the smallest impulse or feeling is contained all human activity.

If we know a little hunger, we know starvation. If we have ever felt ourselves even a tiny bit badly treated by power (i.e., on the wrong end of it), we know politics. If we have ever made a small mistake about which we feel terrible, we know sin.

(The great Israeli writer Etgar Keret discusses this idea beautifully here, in the lecture portion of the book.)

Process, we might say, is the way that we get our imagination to start including experiences not our own – experiences we have never had and never will. This, I think, is the quality you so admire in Faulkner et al – each of whom had, after all, probably fairly quotidian lives. (I’ve seen Faulkner’s writing room and his small, modest desk, and I remember thinking, “Wait, Absalom, Absalom was written there?”)

So, it’s not the life that makes greatness; it’s the mind, expanded by the practice - the practice of working closely with language in order to produce a new and higher category of thinking within ourselves.

Great writing stems from the idea that what’s happening to us down here matters and is sacred. Not just the big things, but every little thing.

That’s genius: the ability to feel, truly feel, that everything matters.

Every person matters; every movement, every shaft of light; every strange inclination, every twinge in the calf; every person we might normally overlook, everything that we normally consider “unliterary.”

It all matters.

Wouldn’t it be amazing, to really feel that way?

Aren’t we fortunate that, every day, through our work, we get to, at least, aspire to feel that way?

I want to thank you again, dear Questioner. I’m sure people will, inspired by the energy and emotion of the question, have valuable things to add.

Also, for those of you who are free subscribers, I’d like to invite to have a look at what’s happening on Sundays, on the other side of the paywall. This week, we’re discussing Isaac Babel’s “In the Basement,” a pretty good embodiment of all we’ve been talking about above - a story set, mostly, in one simple place (a basement, yes) that ends up being about class and striving and shame and families and….well, everything.

I have another, slightly piqued comment in response to the questioner… .

You talk about Hallmark TV, Hollywood writing and you dismiss it all.

I used to do this, I used to want to be Faulkner (now I want to be Steinbeck… ). I dismissed romantic comedies and superheroes and tv as all shite.

But then i met people who love those genres. Genuinely love it, they sweat blood trying their absolute hardest to write the best Dan Brown novel they can. And the truth is, it’s not easy to do that either. It is not easy to write a Marvel film, or a sexy page turner or a superficially light but entertainingly forgettable 2 hour film or a 10 season family comedy.

It’s basically not easy to write full stop.

I think having respect for all writers, for all those people who actually finish something and then have the balls to get it published, made or seen… helps your own endeavours. Maybe they deserve a little more of your admiration, not because you like their style, it’s not your bag- it is a lot of people’s bags- but you can still learn from them. They do what they love and I take my hat off to them.

There is really almost nothing to add to what George has so generously written here today. What a beautiful answer to an honest, searching question. THAT BEING SAID, being me, I do have one tiny thing I feel I can add in hopes of being helpful. Questioner, you write: "My work isn’t yet good enough for me, though." And I want to say, yes. Same here, all of the time. "My taste doesn’t translate into prose." Right--I feel the same way, too. "How do I leave the false but comfortable behind?" All i can say--because I can relate to you, I know what it's like to feel "my work isn't good enough for me," etc.--is that a writer has to just keep writing. For some of us, it takes years and years and years to finally write something where we can say Yes, I did it. Keep going, that's what I want to tell you. Struggle on! You WILL get there. I know you will--your letter alone attests to your ability to string words together, to express yourself on the page. And you want it so badly--more than most people, I think. The only way to get there is through--words and more words, over and over again. It's frustrating and demanding and often a person wants to give up. But I have faith your voice willl appear to you and you will soon enough know how to tell the stories ONLY YOU CAN TELL. Thank you for your question, which I think will make a lot of people feel less alone. And George, thank you for your lovely reply.