Office Hours

To flashback or not to flashback...which reminds me of a time long ago, when....

Q.

So, here's my question: Most authors and teachers advise against flashbacks. You also brought up that they put too much stress on the reader, and we risk losing them. I’m currently writing a novel about a homeless person mainly to answer the question: Why? I found that I needed, in my mind at least, to ground that person in the daily grind of being homeless as a starting point, and then go back to the past. I've written chapters that start in the present, but then revert to the past, or whole chapters set completely in the past. Is this a deal killer for the reader and should I try to rearrange things chronologically?

A.

Such an interesting question. First, to clarify – I’m not at all “against” flashbacks. I actually love them and love doing them. I just notice, when I’m reading one, that processing a step back in time does require a little extra energy. Doesn’t, at all, mean we shouldn’t do them. It’s maybe, a bit, like staying up too late. Might that have a consequence? Sure. Does that mean we don’t do it? No – we do it, and deal (cheerfully) with the consequences the next morning.

But we’d want to ask: Why am I doing this? Is it going to be worth it?

And here’s where each writer distinguishes herself, by her answer to that question. The structure of a book is an enactment of a belief system, if we really think about it. What is allowed (in your book) and when? What are the “rules” that you have internalized in your writing that pertain to, for example, flashbacks? Is there a relation between those rules and…your sense of life? That is: are those rules meaningful?

An aesthetic system, really, is just a set of guideposts we’ve made, for ourselves and by ourselves.

For example: I am going to imagine myself happily writing away….writing a scene set on a certain day and a certain place. A guy is walking down a sidewalk….

When might I go into a flashback? That is, when would I “allow it,” i.e., under what conditions would I be willing to risk that slight energy loss mentioned above?

Well, my answer is: I “allow” a flashback when I find myself going into it naturally; that is, when it is so natural for the character to look backward/remember that I can’t stop him. Often, I don’t know, at first, why he is (why I am) feeling compelled to do that. In fact, I’d be a little suspicious of the flashback if I did know – if, for example, I felt myself articulating something like, “Well, we need to know why he’s so insecure.” That may very well turn out to be the work the flashback does, but, for me, I’d rather not know what I’m in search of, at the time I start wandering off. That result will be, as they say in Hollywood, “too on the nose.” (The writer already has a theory and is just using the flashback to prove the theory.) I tend to use flashbacks in a more exploratory way – a way to get the character thinking privately, so I can come to know him better and thus put him more firmly in harm’s way (ha ha, and yet not ha ha).

But, come to think of it, there is sometimes a slight flavor of intentionality…I can give you an example: in a recent New Yorker story of mine called “The Mom of Bold Action” (which is also in my forthcoming book, Liberation Day) there’s a place where the main character remembers her dead cousin, Ricky, who, in life, was kind of a mess. This flashback lasts for three full pages and goes (quickly, selectively) through Ricky’s whole life. It’s kind of funny, but (per my self-created aesthetic) it shouldn’t be in the story just because it’s funny. It should serve some bigger purpose.

I can remember exactly how the flashback happened. In the story, she’s just passed judgment on a man named Dimini, for not reining in a wild adult nephew of his. Then she lightly corrects herself: “Anyway, it wasn’t his job to control his stupid nephew.” And then I wondered: “Isn’t it?” That is: “Is she right in that statement? Is it in the story’s interest for her to be right about that?” That is, I felt…an urge to watch her interrogate her own statement.

And so, my mind wandered off, essentially looking for something in her life that might support (or refute) that idea she’d just had. I was asking (and she was): “Do I believe that? That we aren’t responsible for the behavior of our relatives? Has my own past behavior been consistent with this statement?” (I’m making this sound more formal/fancy than it was. Imagine if a character said, “It’s terribly wrong to cheat on one’s spouse.” His mind would instantly go to his own case; either he has never cheated, or he remembers a close call, or he has cheated and then has to justify that to himself.)

Anyway, here, I found myself intuitively assigning her a cousin who wasn’t the greatest: this guy Ricky.

So, the flashback served, in the end, as a chance for her to self-examine (“To what degree have I taken responsibility, for my errant family member?”), which was really a way of asking, “Would I be right to be mad at Dimini because of his behavior re his rotten nephew?” She concludes, based on her memories of her interactions with Ricky, that she has no such right. But in the process, the flashback also generated something: this dumbass, Ricky, whom she loved, even though he was rotten. And this, it turned out, came in handy toward the end of the story, in a way I won’t go into it, in case you want to read it.

But, in the moment, we accept that long flashback (I’d say) because: 1) we feel that it’s needed (we feel it examining the truth of the statement “It’s not one’s job to control our family members”), and 2) it has sufficient charm to compel the reader through it.

A slight aside, to make sure I’m answering the question I was asked...

Above, I guess I’ve been talking about the kinds of flashbacks that might occur in third- or first-person real-time narratives. (We’re on a certain day and a character remembers something that happened earlier, and then snaps back into the present moment of the story.)

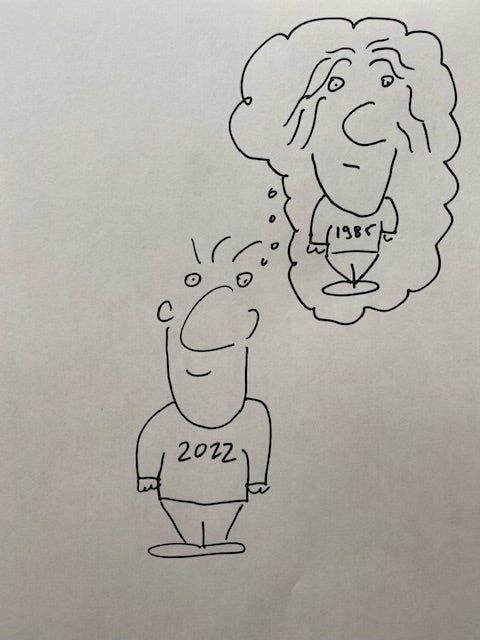

Now, it sounds as if the flashbacks you are contemplating, dear questioner, are more of the structural variety – we get a chapter set in, say, 2022 and then go back to 1985 or whenever – but I think the same idea applies: one of your tasks is going to be coming up with (or, more correctly, discovering) a system of practices for yourself to follow re your flashbacks. What prompts the end of a 2022 chapter and the beginning of a 1985 chapter, for example?

Above, I claimed that a book’s structure is an enactment of a belief system. Here, in your book, you are going to be saying something about the world by the manner in which the movement back and forth in time is triggered and then accomplished. Say, for example, that every jump back to 1985 is triggered by a sensory experience the narrator has in 2022. (He walks past a burger place and remembers one at which he used to work.) That’s one world. Say that movement is triggered by him or her finding himself in a certain emotional state (he’s angry, say), which reminds him of an earlier, circa 1985, fit of anger. That’s a different world. Say there’s no precise trigger – you just go back in time whenever you feel the action in the 2022 chapter is played out. That’s a third world.

What does this have to do with your “beliefs?” Well, in those transitions, you are telling us something about your notion of cause-and-effect – you’re implying, in the second case, for example, that this fellow’s anger has been a constant throughout his life – you’re calling attention to that. (Or maybe his anger now is greater, or less, than it used to be – that says something too.)

In other words, structure is a way of subtly conveying emphasis. We are telling the reader where to look.

So, this question of how to handle time in your story about a homeless person is one of the ways that your book is going to mean something – the reader will glean an extra dollop of meaning from the way in which you transition from past to present.

Another thought about flashbacks on the smaller scale (that is, those contained within real-time stories). (And again, I’m not claiming to be offering any sort of universal truth, but merely one of the “rules to write by” that I’ve internalized), but: a flashback should be entered into naturally and go on for as long as would be believable.

Here’s an example:

So, my character (Larry, let’s call him) is walking past a store, smells some roses, remembers his sister’s funeral. For how long is he allowed to “remember” this? I confess that I have a fondness for flashbacks that work like real-life memories do: they arise and fall away, within a limited time span. Also, they might follow the natural play of mind and suddenly lead to something else: Larry smells the roses, remembers his sister’s funeral….it was amazing that Amy had come to the funeral at all, after what Sue did to her. But Amy was always like that, really good-hearted. Even when Roger left her and took both cars. He’d always wondered how Roger had managed that: taking both cars. Had a friend helped him with that? Well, that was Roger: mean as hell, but with lots of friends.

And then…I feel (I am feeling right now, as I goof around with this)…that’s enough. Time for a bus to go by and splash some mud on Larry, or for him to see an old girlfriend coming by in the other direction or….well, whatever – just something to get us back into the real-time narrative. Because the meter has been running all this time.

At least that’s how it works in my fictive world.

How does it work in yours?

On the other hand…I feel here a need to recall the Shonda Rhimes/Norman Lear mantra from a previous post: “You can do it if you can get away with it.” That is: all of the above being said, a flashback can be as long as you want it to be (as long as delights you). My memory is that there are flashbacks in Ulysses that go on for a much longer time than would be felt as natural. And they, uh, work just fine.

On the (other) other hand: we all know the feeling of resisting a big old flashback that’s been dropped down in a real-time narrative that was going pretty well, a flashback that is a big buzzkill because it is so lazily over-explanatory and seems to want to do so much assuaging work – this resistance comes, in part, because that flashback is violating reality – no one “has” a forty-page flashback in real life. It might also feel too convenient – like an unsportsmanlke workaround, trying to evade the constraints natural to a work of fiction, constraings that a beautiful work of fiction doesn’t want to evade, but, rather, consent to, and work with.

The real point of this post, I guess is: there are no rules. There’s only physics – the physics of the form. The physics of readerly patience and enthusiasm; the physics of keeping the reader reading.

We don’t have to submit to that physics, but we have to know that it applies to us, and that, therefore, we are in a dance with it.

So, in your book about the homeless person, dear questioner (according to me): the reader is going to feel a little resistance each time you propel her back in time. That’s o.k. Your job is to deal with this, compensate for it, make it easier, make it (even) part of your plan for making meaning in your book – convert it into an asset, essentially.

When we write and edit, we are steering by certain preferences within us. (We saw this when we did that cutting exercise earlier, back over there at the DMV.) But this applies to every choice we make. There is no God of editing, going, “Thou must always have the perfect mix of real-time action and flashback, peppered with the optimal combination of dialogue and description.”

The world – the real world – is so vast and complex compared to us, we poor little perceptual machines, that when we ask, “What is the world like?” there can be no correct answer. It’s every way, all at once. It really is. But we try to answer, don’t we? That’s fiction. Fiction is us, sweetly trying to say how things are. What lovely freedom we have, knowing that reality is not just one fixed thing.

However we declare life to be is – it is! Now: out of all those myriad ways, which feels most vital (truthful, urgent) to you? This is what we are trying to discover, as we experiment with different forms and structures. These are part of our answer to the question, “What is the world like?”

Hemingway’s terseness is part of his answer (it says “damage” and “the caution that comes from realizing how fraught it all is.”) Likewise, the kindness one feels in Munro’s small digressions, which often remind me of local, rural talk. Likewise, Kerouac’s run-on sentences which, at their best, feel like the joy a young person feels at being, finally, out in the world on one’s own terms. These are all technical qualities of the work that convey a moral positioning as well.

So, the best case is when it feels that a certain internalized choice has some relation to what we “believe” about the world. (This, for me, is often marked by a feeling of joy or enthusiasm in the doing.) The stuff above, where I talked about a flashback needing to feel “natural” – I feel that that comes out of my life. That’s the way I feel about life: that “a moment in life” is really, seen from above: some number of those little perceptual machines, thinking, thinking, thinking, while moving around and then…two of them interact, driven by the thoughts they’ve been having, thoughts they have mistaken for “reality.” So, I want my fictive world to look and feel and operate like that. I want thinking to be as real and tangible and finite as walking or juggling or falling down a manhole. Hence, a flashback, which is, after all, just a memory, briefly had, in the mind of a character, can only last so long (in my stories). There are stories that absolutely ignore this idea…but they are not mine.

So, again, all of this really comes back to the notion that the artist’s job is to choose. And craft is the ritualized way that we check to make sure we have chosen, in all of the places where we conceivably might have done so.

Next Sunday, we’ll be doing another one of our “silly exercises”- this one is called The Automatic Novel Chapter. Join us over there, by becoming a paid subscriber…

I dunno, my memories can go on for quite a while. One time I ate a madeleine and had a flashback for like a thousand pages.

i had no idea that "authors and teachers advise against flashbacks." That sounds crazy, to me. Flashbacks can be fantastic! And necessary! One thing I've noticed by reading these threads the last few months is that a lot of people have been given a lot of rules. There really are no rules (George has said this as well). You can do whatever you want as long as you do a good job of it. (I've seen Alice Munro mentioned here. She is the queen of writing all over the place in time. Her use of time--well, if you haven't read her, dive in anywhere. She's not just digressing--she often goes back and forth. It's amazing to see what she can do with chronology and time.)

To this particular questioner, I hope you don't mind my unasked-for advice. Just write your novel in any way that feels right to you. Don't listen to any rules. Finish your book and then analyze it. You'll see what's missing or what needs to be added. If your flashbacks or sequences aren't working, you can revise them. If you need more, you can put them in. I'm sure you're already on a good path. Listen to yourself and do what you feel is right.

I'll shut up now. Thanks for reading.