Q.

In a terrific Zoom class you gave around the time of the publication of “A Swim in the Pond in the Rain,” I think you said that you did not like “The Lady With the Dog” at first but came to love it some years later. If I’ve got that right, how did you come to change how you thought and felt about the story?

A.

Yes, and this, of course, relates to last week’s Office Hours as well: what do we do with a story we don’t get, or simply don’t like?

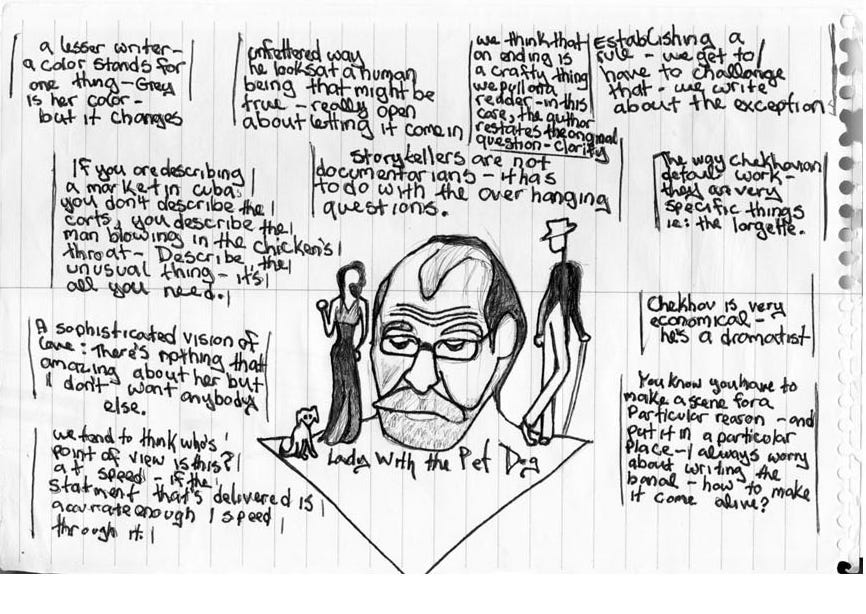

In this case, the answer was really just time. I think I read that story first when I was in college, when I was a staunch Hemingway devotee and felt attracted to stories about exotica – wars and travel, and so on. I was also very much a “voice” person – the more distinctive the better – and Chekhov’s voice in that story struck Young Me as pedestrian: flat, every-day, non-performative. I was also not a very good close reader and failed to note the cues being given by the story or feel those definitive pulses or stairsteps we talked about here in Story Club – I didn’t feel the story as a series of consequential developments but basically just as a bunch of middle-class blah-blah-blah.

But I knew the world thought it was a great story, and soon I was in graduate school and my teachers there, for whom I had immense respect, thought it was a great story. So, I had a sort of divided reaction: 1) There must be something about the short story form I don’t understand and 2) I still don’t love “The Lady with the Dog.” I didn’t hate it - I just didn’t love it.

And to my credit, I “honored” both of those items. I honored the “meh” gut feeling associated with item 1 — and that was good. Because those gut feelings (“I like this, I don’t like that”) are all a writer has to work with. To move away from them too much is to risk disaster.

But, with the world and my teachers in mind, when I dismissed “The Lady with the Dog,” I did so (honoring item 1) while slightly shifting the burden to myself, putting the disconnect down, in part, to some possible blind spot I had in my reading. It was kind of an “I’m just not ready for this yet” feeling, I guess.

Years passed.

Meanwhile, I was learning to read stories with more attention, and on the assumption that, in the work of a serious writer, there are no accidents; that is, every move and every effect has been, if not intended, then blessed. Therefore, we have to always be asking, “Why is the writer telling me this?” and “Why is this being mentioned right here?” “It doesn’t make sense to me - why does it make sense to the writer?”

The other thing that was happening – not unrelated to the first – was that I was becoming a better writer. By working through my own stories line-by-line, I was becoming aware of the “no accidents” principle above, and was being brought, again and again, to various crossroad moments in my own work.

At a certain point in an in-progress story, there before me would be two (or more) paths. I’d follow one, and it would turn out to be no good. Then I’d retrace my steps and follow the other one. Through this process, I started to understand how stories come to mean something – it is by way of just such choices. (These crossroad moments are, we might say, meaning-rich.”)

This, in turn, made me more aware of how many choices had been made in a finished story.

That’s what a story is, really: a series of choices that the writer made, in order to maximize the meaning of the story/the light coming off it.

Going back years later to “The Lady with the Dog” – and I think this would have been when I first started teaching at Syracuse and had decided to do a Forms class on the Russians – it was as if a previously flat landscape had suddenly sprouted hills and creeks and houses – it seemed that every line of the Chekhov was now fraught with meaning, with evidence of authorial choice-making.

The whole idea – and this is true of crazy, experimental stories as well – is that, on the other end of the creative process is a human being not entirely unlike yourself, who has chosen to spend some number of her precious hours on this earth shaping and sculpting the story you’re reading. Therefore, it must mean something, something important. (This isn’t always true, alas – some stories really are dull, or strident, or lazy, or preachy – but it’s good readerly practice to assume, for a while at least, that the writer is brilliant and that, if the story isn’t reaching you, it’s because you’re reading it at the wrong frequency.)

Life is short, of course, and some stories ought to be discarded, but we could see the above attitude as a sort of due diligence, especially when reading something alleged to be a classic.

I might also make a distinction – with some stories, I just feel, “No. I get it, but there is nothing here for me.” And I rather happily let those go. With others, the feeling is more complex – “I don’t get it, but I feel I am missing something, and it might have to do with me.” In this feeling, there’s a trace of retreating respectfully, like: “No offense, story – I bet I’ll be back later. Just…wait here for me.”

We might also try to read less to judge, and more to improve; we aren’t doing jury duty on the ultimate worth of a story, we’re scavenging through it to see what we can learn from it; we’re hoping it will have some happy effect on us, even a slight one, and even if that happy effect turns out to be rooted in our aversion to the story.

This stance puts us, I’d say, in a slightly different relation to a story we’re reading.

Another quick thought: we can grow and learn by reading, not only stories that don’t speak to us, but plain old bad stories. We can read along until the sense of badness first hits us and then ask ourselves why. What constituted “badness?” To what are we reacting? We can do some thought-experimentation: Could there have been a way to tell that part of the story that would have been….less bad? What was the fatal error? The moment when the writer first started to lose us? What quality was the writer manifesting in that moment, to which we are reacting/feeling averse?

When we read like this, we get a nice glimpse into our own esthetic system – what we value, what we feel averse to.

There’s nothing like a strong reaction to tell us what we believe.

When I reacted indifferently to “Lady with Pet Dog,” it was partly because, at that point, I had an aversion to stories about “regular” people. I wanted to read about adventurers, rebels, outcasts. If I, at that point, had been my own teacher, I’d have asked that young guy why he had this aversion. Mustn’t there be suitable material for literature everywhere? Wherever several people are gathered? In his own childhood neighborhood, for example? Within his own circle of friends and family?

I doubt young me would have taken the bait – he was pretty stubborn, that kid – but it might have planted a seed.

In any event, what converted me to the literature of real people – of the mundane, sweet, regular, compromised-laced lives most of us lead – was that I started living that life myself. Got married, had kids, started working a job that was anything but adventurous – and I found, of course, that there was so much dearness and conflict and drama in that life, enough to fill a million books. The earth under my feet (well, mostly it was that scruffy corporate carpet) suddenly came into focus, as did the conference table piled with technical reports, and the living room floor littered with Legos and drawings done by our kids, and all the real, actual American stuff that I’d never before seen as potentially part of literature before: berms, TGIFs, squabbles over photocopier time, the rain coming down in front of the window of a Wendy’s drive through, drunken passionate outbursts at office parties…

Hemingway and Kerouac and the worlds they wrote about came to seem, to me, somehow less, less than those in Tolstoy or Dickens or Carver – less interesting and more limited. (Of course, they weren’t, and aren’t — they were just less interesting to me, at that time.)

But this new view meant that I could mine my whole life in my writing – my actual childhood and my new and ongoing struggles with money and class and work and all of that.

No trout fishing in Spain necessary.

And suddenly “The Lady with the Dog” seemed, not only magnificently shaped, but concerned with a type of struggle that felt familiar to me - human-scaled and important. Concerned with compromise and with love of different varieties, familial and romantic, acquisitive and generous.

With every passing year, that story seems more profound – not only, now, about romantic love, and one particular affair, but about each person’s attempt, in his or her one precious human life, to move through superficiality and selfishness to the deepest form of love of all, whatever that may turn out to be.

And, as we’ve discussed here, that’s the question the story might ultimately be asking: “What is the deepest form of love of which we’re capable?”

And who’s not interested in that?

Over behind the paywall, we’re beginning the process of applying some of the story mechanic principles we’ve been studying to newer, stranger works, and are in the midst of talking about “The School,” by Donald Barthelme, and my response to it, an essay called “The Perfect Gerbil.”

I’m reading this in the hospital. My daughter gave birth to a girl over an hour ago, and we’ve been waiting on her twin brother to emerge ever since. I think he’s already a close reader; of cave drawings, perhaps.

As often occurs here, for me anyway, this post of George's feels like wise, loving observation of the world as much is it portends to be about writing and reading. I think that's what I love about StoryClub: it's about presence, observation, perspective instead of "here's how to write a story". I have enjoyed the stories presented here because the older I get, the more I appreciate restraint, subtlety and insight, a sort of shaker "plainness". That's what I associate with excellence and mastery. As a younger man I think I was more impressed by shiny clever things. Not so much anymore, including stories. I am so unimpressed with extensive description and overly bizarre characters. They remind me of a loud party guest going on too long about themselves and their adventures. For me it's a difficult enough task to deepen my understanding of the world and the people in it. The other stuff is just a distraction. Yeah, I know some people find the embellishment helpful or entertaining and it draws them into the kind of understanding I'm talking about, but I lean toward the zen version. Less is more.