Q.

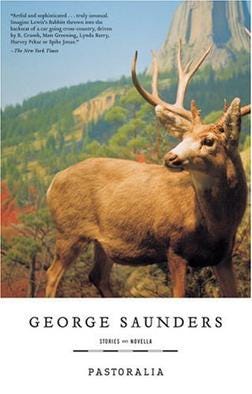

Earlier this year, I read "Pastoralia" again after hearing it mentioned in a 99% Invisible podcast episode about inspiration. I became obsessed with the story; it blew my socks off this time around. I work for a large company that had layoffs earlier this year and communicated about them as confusingly as the company in your story. Amidst this turmoil at work, I found occasions to laugh at the absurdity of working in corporate America. Thank you for the laughs! (And thanks to the universe for my good fortune, which spared me from the layoffs.)

As I picked this story apart, I discovered that the version you published in The New Yorker is much shorter than the novella in the book. Given what we know about your process from the deep discussion of “CommComm,” I'm now wondering: How do you set about stretching a story from its original form into something longer? How do you know which ones would benefit from more breadth?

Many thanks for your time in reading this far, and for all you've shared with us here.

A.

Thank you, for the question.

As I remember it, it actually happened the other way around. I had what would end up being the book version of the story, sent it to The New Yorker, and they liked it, but it was too long to run in the magazine. So, they asked if we might try to make a “magazine version” – cut my version down to size. I thought about this a little and then decided it could be a good challenge. The full version would still appear, later, in the book, and, in the meantime, I’d get to share the story with the world and get all of the associated New Yorker buzz and fun. So, I basically approached it as a technical challenge I was allowing myself to undertake.

Elsewhere I’ve referred to “shrink-wrapping” a story. Here I was essentially shrink-wrapping something (extremely) that I’d already shrink-wrapped. But I said to myself, “Consider this new version as an entirely different work of art.” I also had in mind that old Reader’s Digest “Condensed Books” series. Kind of blasphemous, that series was, but, on the other hand, I used to read those greatly reduced novels with a lot of pleasure (not realizing they’d been condensed.)

I also had the help of Deborah Treisman, the legendary editor there at The New Yorker, in deciding where to make those cuts.

As we were working through the story, I kept saying to myself, “These cuts can always go back into the book version.” Now, that’s what I always say to myself when making cuts for the magazine – but I almost never end up putting the cut stuff back in.

For example, we did some fairly extensive cutting on the story “Tenth of December,” ostensibly just to get it down under the magazine’s word-count limitation, but when I went to put the book together, none of those bits wanted to come back in. It was as if, once cut, they had literally died on the cutting room floor – they’d lost their life-force. When I tried to put them back in, they seemed clearly extraneous, goiteresque, even.

And actually, there’s one more element to this saga. If we rewind back, to six months or so before I sent it to The New Yorker, I was having a crisis of confidence in the story. I was – well, I still am, as you will, by now, know – a bit of an efficiency freak. The story, or novella, or whatever it was, had some pretty long communiques from the main character’s corporate handlers, in the form of faxes they’d send to him.

Well, Mr. Efficiency took over one day, had a bad read, and lopped all of those bits out. Very efficient indeed! I’m guessing some of you are familiar with that mindset: “If it isn’t absolutely necessary – if I can’t name the exact work it’s doing – out it comes!” For me, this is a form of wanting to move away from all of the messy mystery that makes a story good and toward a more comfortable, reductive, technician’s view. “If it’s not working always cut it back. Always.”

But this isn’t true. (Art doesn’t like “always” and “never” very much.)

I gave the reduced version to my wife, Paula, to read (she’d read an earlier draft too) and she said, “Huh. You just cut all the fun out of it.”

So, I put the fun back in, which resulted in the long version that, now (at the moment of possible acceptance), The New Yorker was asking me to cut down. HOWEVER….the approach they were suggesting wasn’t to cut out those corporate communiques, but to make trims throughout.

We went through the editing process and there was, indeed, a coherent “magazine version” in there, which was published. When book-time came, in this case, I found that I was putting a lot of those cut bits back in - not all, probably, but most.

So, ultimately, there were three distinct versions of the piece: 1) my fun-removed, shorter version, that has never appeared anywhere, thank goodness; 2) the full version, that included the communiques, and which later would up in the book of the same title, and 3) the magazine version.

This is all, at least in my mind, in keeping with an idea I’ve expressed here before, that our work is not us, but is of us. It’s coming out of us, for sure, but inside us there are so many valences and flavors and speeds. We are, then, when we’re working, just managing that bounty in such a way that the final product – the finished story – is, we might say, “worth it,” however we define that term. For me, this means: fun, original, powerful in some way, with at least a flash of the “real” me in it - that “me” that emerges after a long period of revision, and that I prefer to regular, everyday Me.

So, if I asked you to produce an 8000-word version of your 12,000-word story, and you were happy with the 12,000 word version - it would be interesting to try. What different kind of light might come off of that short (even too-short) version?

I think this attitude can be useful in a practical sense, as we try to find the best version of a given story. It gives us some flexibility; in a sense, we’re saying that there is no ultimate version of a story, just the best version for a particular usage. (Different versions are giving off different kinds of light.)

This isn’t quite true, of course. For me, the most important “particular usage” is that the story appears in a book. I am always thinking about that: which version do I really believe is the most artistic and powerful. I want that story, in that book, to have some life out in the world. So that version is the one I’m really trying to find: the one I want in my book.

Having a story in a magazine is a lot of fun but stories in magazines fade. So, the feeling with “Pastoralia” was: let me have the fun of having this story in the magazine, and also the fun of having its longer self in my book, later. Can I do both? I just said to myself: Sure you can.

I sometimes think we want to strive to have a mix of two mindsets: 1) the extremely controlling, nearly obsessive view that wants to make our stories perfect and will put in endless hours to do so, and 2) the playful, exploratory view, that is all about “bringing forth” and then quickly de-attaching from whatever particular manifestation the creative urge has produced.

The first, alone, is joyless; the second, alone, lacks rigor. But together, they can produce something beautiful. Part of the individual writer’s challenge, then, is getting the mix right.

We are, really, bringing to bear on our stories the personal tendencies we were born with; trying to apply these in the right proportions and purify them with our editorial attention and thus “take advantage of” them, or “bring them to their highest pitch.” In this way, we’re celebrating these tendencies, even the ones which are, in real life, a pain-in-the-ass to have.

So, in this realm, nothing about us – none of our tendencies – is “wrong.” Everything about us is a potential source of energy. If it occurs in us, it can be profitably used. And if it occurs in us, it likely occurs in other people as well. In this way, the personal can become universal.

Flannery O’Connor, it would seem, had an acerbic side (to her personality). Tolstoy could be quite opinionated. Isaac Babel was a bit of a perfectionist.

These “personality” traits show up in their respective stories, purified and put to great use.

We aren’t trying to excise a tendency, but to honor it and talk nice to it so that it will come to the table and be its best, purest, most expressive self for us.

I wrote an essay for a journal years ago. Might have been about 2,000 words. It was well received and I thought it was pretty good. Then it got more attention and another journal called, wanting to publish it in their special back page feature position. It was an honor. It was also limited to 1,000 words. I had to cut my piece in half. I bled. It got tighter. My wife read it and thought it was much better. She couldn't even remember the parts I cut. Then I heard from the Utne Reader, who wanted to promote it with a brief version. They needed it to be 500 words max. I cut it in half again. I bled more. The story started to bleed. I think I passed the point of coherence and it turned into a synopsis. But they published that and I enjoyed the continued publicity. Then I heard from the Pearson Testing Service. They wanted to license it for an essay question on their standardized tests. I thought it was joke. I asked my daughter in law who is an educator. She said, on the contrary, it was an honor, go for it. So I asked how much they wanted. They said 300 words....and...I cut it again. So the synopsis became an excerpt. I learned a tremendous amount about how much fat can be cut and I learned how much of my own absolutely fabulous words were simply expendable, without losing the point. I also learned how it can go too far, lose the overall grace but still communicate the main points, enough for a student, somewhere, to react to it and bring forth their own ideas, and start the cycle over for themselves. Quite the set of lessons about writing and life.

Oh, Pastoralia. The first George Saunders story I can remember reading. (Is that right? I think so.) And I remember a couple of things. One, that whoever wrote that story was out of his mind--i mean, the world he conjured! And, two, I remember how that story stuck with me for a long time. George, i hate to say this, but it stayed with me because the story made me feel so bad. I just wanted to go to that crazy place and pull those poor souls out of those cages. And i've more or less hung onto that feeling all of these years which, I see now, is nearly 23 years.

But what I want to really say is how much I love this: "...nothing about us – none of our tendencies – is “wrong.” Everything about us is a potential source of energy." And also this: "We aren’t trying to excise a tendency, but to honor it and talk nice to it so that it will come to the table and be its best, purest, most expressive self for us." I try to honor my tendencies, but god damn if a lot of the time they either sit under that table, or they stand on top of it, shrieking. Well, I'm working on it. It's a long road to come to that place where we love ourselves, i guess.