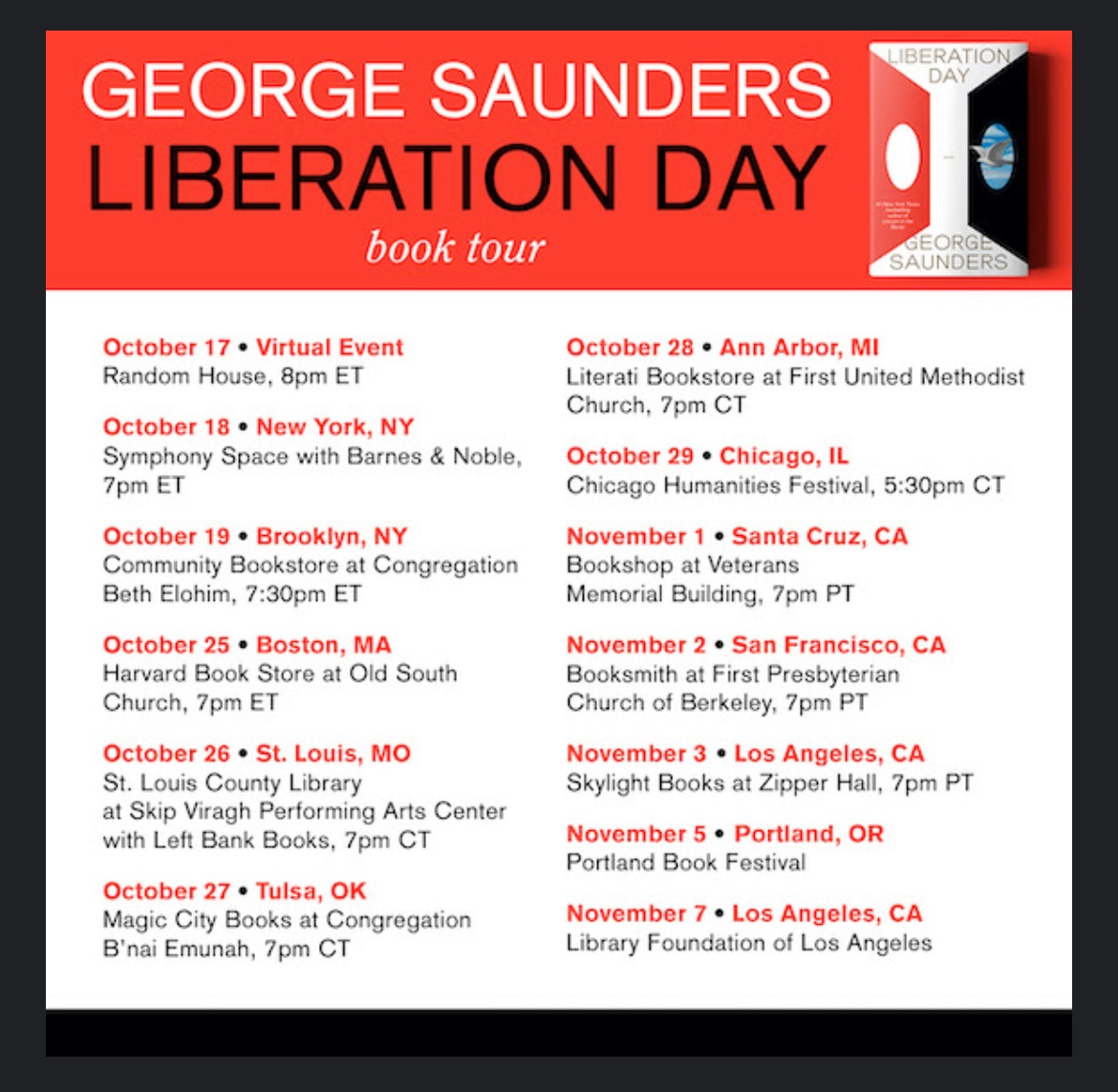

First, I wanted to share this schedule, for the U.S. part of the tour for Liberation Day:

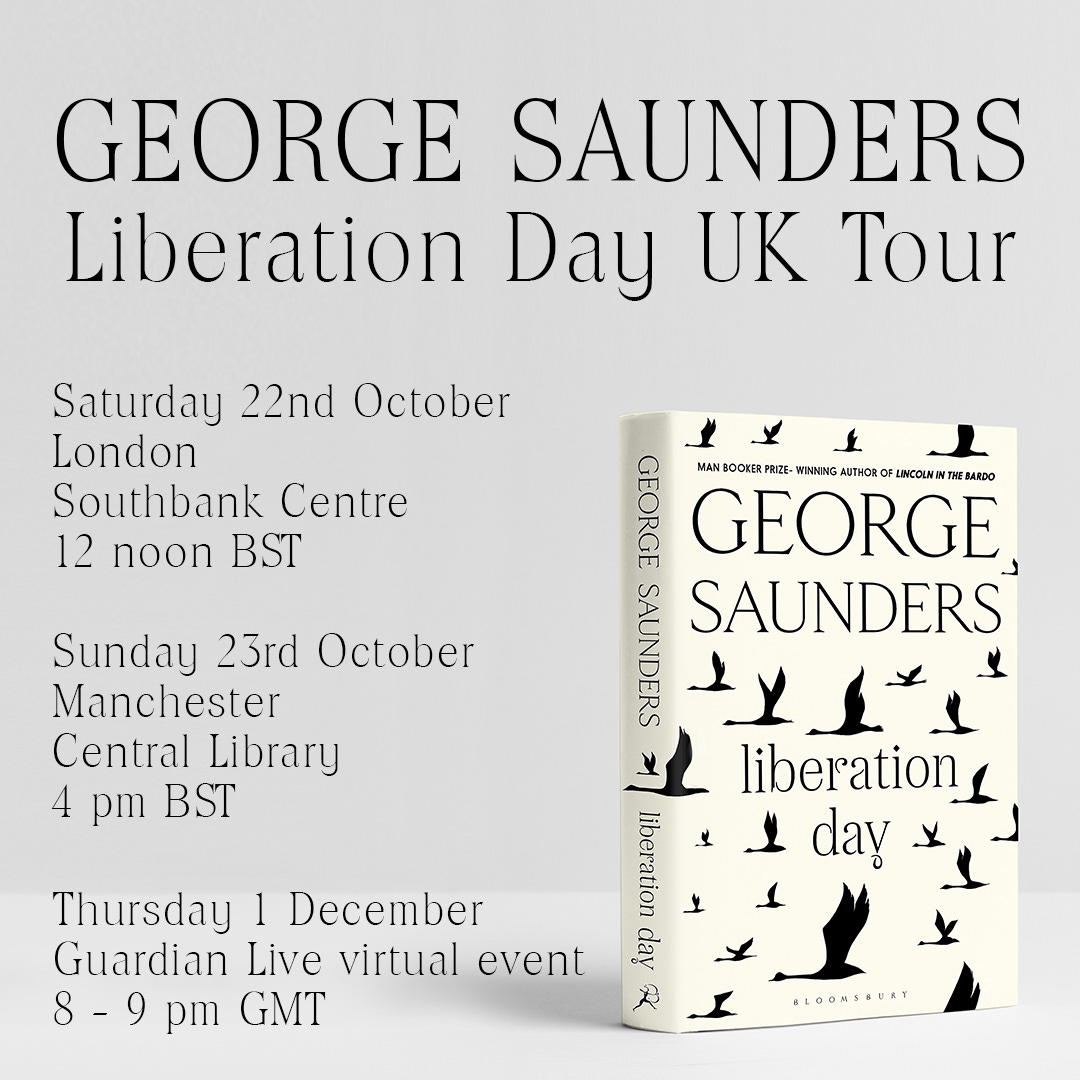

As you’ll see, there’s a little gap there, between October 19 (Brooklyn) and October 25 (Boston) — that’s when I’ll be in England:

Hope to see some of you out there. It’s coming up fast, seems like…

Now, on to the question of the week:

Q.

What ethical considerations would you make if writing a story that uses, in part, the experiences of someone reasonably close to you, even if the character was quite different to the person?

I’m itching to explore a story using my own experiences and those of a relative, however am worried that if the story ever saw the light of day, that person could be offended.

A.

Yes, this is a great question. I am so terrified of hurting someone’s feelings that – well, I think that’s one reason my stories tend to be so weird and made-up, generally. I’ve had a few occasions where someone recognized themselves, or thought they did, and I didn’t find it pleasant at all.

I wrote a story many years ago that closely tracked my time on a roofing crew. It was published in The New Yorker as non-fiction and apparently, the roofers on whom the story was based read it and weren’t happy with it. And I didn’t really blame them. The whole thing made me surprisingly unhappy. Later, I “converted” the piece to fiction, changing the names and so on, and thereby excusing any invention I’d done, but it still bothers me that they felt misrepresented. Of course, there’s another layer to this – I was accurately reporting some thoughtless behavior on the part of a few of the guys, and maybe that’s why they didn’t like it. So, in a case like this, maybe that’s part of the writer’s job, to say what seems true to him and then deal with the consequences. But I have to say, I didn’t enjoy it and even now it bugs me.

The real truth is, my best gifts come into play when I’m inventing pretty much from whole cloth. Something comes alive in me once I untether myself from the autobiographical. Of course, I’m using my life and the people I’ve known (what else is there to use?) but I always feel happier and more comfortable when I’ve severed any overt connection to a real person.

I never have it as my intention to “represent” someone. Rather, my intention is to embody tendencies, human tendencies, in specific fictive objects (i.e., characters). So, it’s not a goal of mine to “put” someone in a story, or even to “get someone right.” I know this is important for some writers but I’m not good at it and don’t aspire to it.

I might use part of a person – a trait or a gesture or a certain way of speaking or what they have come to represent to me – but that thing is usually pulled out of the real-life context and used…for something else. It gets reconfigured by its surroundings. I’m trying to extract some crucial human thing and it really doesn’t matter to me who it came from or if I end up changing it in the process (for example, putting a trait from one real person into the “container” made up of the traits of another person (or two, or three).

So, for example, I once worked with a woman who briefly served jail time for check fraud. She vanished from work for a month or so, then came back. She was a good worker and a nice person and a lovely work friend. But that detail about the bounced checks stuck with me and many years later (last year, in fact) I wrote a story that has that detail in it – a woman comes back to work after serving some time in jail for bouncing checks. But the character I built around that detail is not, at all, that co-worker. Not at all. The fictional woman does something else, in the story, that gets her fired, something that her archetype never did, or would ever do. But I considered the real-life woman not as a model, but, rather, as someone from whom I could freely extract that one factual detail (the bounced checks). And then I felt free to graft that trait on to my fictional woman, to maker her be whoever she needed to be, to serve the story.

Or I might notice a certain behavioral tendency – someone is always completing someone else’s sentences, for example. I pull that tendency out and assign it to a character, to whom I also ascribe other traits, some invented or lifted from a second person. The point is just to make a fictive construct (a collection of sentences, really) that feels like “a character,” and I will use anything that writes well to do it.

But just by looking at all the great books that have come out of personal, biographical experiences, we can see that the above answer is not sufficient. It’s just my answer, formulated in response to what works for me. But clearly some very great writers do write directly from life, and beautifully, consequences be damned. (See Proust, see Maya Angelou, see Knausgard, see Jean Rhys, see Kerouac, and on and on…)

But it’s a fraught choice, to use one’s real life in a book. But it might be necessary, especially if the writer has determined, through trial-and-error, that her best writing will come from this approach.

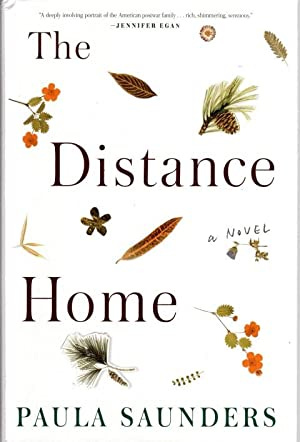

It’s a choice that my wife, Paula, had to face, when she was writing her novel, The Distance Home, a beautiful exploration of her early life with her family in South Dakota. I know it was an issue for her – this question of hurting someone’s feelings and the idea that a writer is always representing just her idea of the past. As it happened, she only published the book after three of the people on whom the main characters were based had passed away.

From my viewpoint, this was the story she was born to write, the story of how life had felt to her. It was one of things I fell in love with about her, in the early days: how deeply she felt things, what a close observer and deep thinker she was about the things that had happened to her. She was a student of, and a wonderful talker about, the dynamics of her family. She has always been very wise around the issue of her family, able to use that system as a stand-in for the greater system, the world; alert to the way that compassion has succeeded or failed in that setting, to the various longings her family felt; a keen observer of love – what it aspires to, how it sometimes fails us, the after-effects of that failure. This wisdom, and a deep tenderness, come alive in her work when she’s writing semi-autobiographically. And it would be a great loss, to her and to the world, to have missed that opportunity.

In a sense, it might have to do with how fully we believe in the power of literature. Might it be worth the discomfort? When I read Paula’s work, and when I hear her talk about her family, I feel that I am being taught about….well, everything; about the way people, everywhere and forever, have interacted. She has wisdom in this area and, if we believe that offering this wisdom to another person might have beneficial effects, then that must mitigate the discomfort we feel.

One thing I’ve noticed – if I start to feel panicked about using a real-life detail, I tell myself not to panic until the final round of edits. So many things tend to disappear as we’re working, so those early worries are often rendered moot.

I wonder if you, dear questioner, might consider discussing this in advance with your relative. I’ve found that, mostly, people don’t mind being written about, if you give them the context (“it’s not you, it’s a character”). I’ve done this before – talked with a relative about the method I use when writing (as discussed above) and this seemed to help, to let them behind the curtain a bit, so to speak.

I expect many of you will have thoughts on this. What advice would you give?

While digging around in my files back in New York, I found something I thought I’d lost forever: an early version of the speech on kindness that later became Congratulations by the Way.

This early version, I delivered at our daughter’s eighth-grade graduation ceremony. That talk went well and so, a few years later, when the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Syracuse (where I teach) asked me to give a talk at a baccalaureate event, I agreed, thinking that I’d just, you know, repurpose that earlier talk. But when I went looking for the text a few days before the event, I couldn’t find it. So I had to start from scratch, writing from my memory of that earlier speech.

Then, last week, digging around in my files back in New York during the Death Cleaning (or the Birth Cleaning, as some of you would prefer it), I found that text, nicely put away in a folder, with a very sweet thank you note from my daughter’s principal in there too.

It was interesting, comparing that version with the later one, crouched over it there in our darkened former basement, when I should have been doing other things…

I’ll be sharing that on Sunday, for paid subscribers...

I think Anne Lamott said it best:

“You own everything that happened to you.

Tell your stories.

If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

That said, I do think some effort to understand the reasons behind the bad behavior makes a deeper, more balanced story. Developing the capacity to look at ourselves from other points of view is a good thing. It’s the way we grow and it doesn’t happen without discomfort.

Wow, this is so timely. I just started sending out a short story that includes a LOT of details from my brother's life--the most "reality-based" thing I've ever written. Weirdly, it's also the first story I've written that got an overwhelmingly positive reception in a workshop. (Maybe I'm one of those writers who has "determined, through trial-and-error, that her best writing will come from this approach"...) I was strongly encouraged to send it out for publication, and I sought advice from many people on how I should approach the fact that, for instance, one character bears a striking (and not particularly flattering...) resemblance to my sister-in-law. They told me to go for it anyway, but I did end up sending the story to my brother to read before I sent it out. I knew I couldn't live with myself if it was published and he was hurt by it. (I'm less concerned about my sister-in-law, mostly because she will almost certainly never stumble upon it.) My brother's response? "Well, that is definitely the best thing of yours I've ever read. Definitely send it out. Also, it's spelled 'Spider-Man,' not 'Spiderman.' You'll want to fix that."