Before we launch into Office Hours, just wanted to share with you this video, in which I talk a little about teaching, made by my good friends on the Syracuse University Marketing team.

O.K., and here we go:

Q.

Thanks for starting this Substack and for writing A Swim in a Pond in the Rain and your fiction which have all been really fun and helpful to me as a guy who doesn’t have an MFA but is quasi-serious about fiction writing. I write about an hour or two each day after the school day is done at the middle school where I work as a teacher’s aid (aka paraeducator).

You talk about expectation-creation as so vital to reader engagement quite a bit on the Substack and in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. My question is, do you consider archetypes and/or tropes useful for the writing process at all, either as a scaffolding or jumping-off point in early drafts or find them factoring into your creative decisions if you notice that an element in a work-in-progress starts to inadvertently resemble a particular trope?

Tropes and archetype appeal to me as a sort of tool or toy, like a new LEGO set waiting to be opened. They come with expectations already baked into them which can be played with, subverted, deconstructed, etc. But it also seems like there is the potential for them to become a distracting or a crutch or shortcut. Or worse perpetuate harmful representations of certain groups (i.e., Born Sexy Yesterday, The Magical Negro) if they are merely obeyed rather than thoughtfully explored and subverted when harmful.

A.

Thanks for the question. And, for what it’s worth, in my view, writing “an hour or two a day” after work makes you, not “quasi-serious,” but…serious. Good for you – it’s never easy to combine the real job of a real job with the real job of writing.

Like the question recently, about the “crisis moment” in a story, yours made me realize that, yes, this is something I recognize from my own work, although I don’t talk about it much.

So, let’s think of a trope as “a convention or device that establishes a predictable or stereotypical representation of a character, setting, or scenario in a creative work (per Dictionary.com).” We might also talk about character tropes (“how we describe characters in a sentence or two…archetypes that have been used for centuries to represent the basic characteristics of human beings….‘The Chosen One,’ ‘The Manic Pixie Dream Girl,’ etc. (per filmlifestyle.com.)

Put simply, I never start with a trope, but I do sometimes find myself stumbling into one. And I usually feel this as a good thing; it means the story has started to move out of my individual imagination and dip its toes into the deeper river of myth.

When I notice the beginning of a trope, I feel a sense of light validation, like: “Ah, my little story has grown up, and wants to be about something!” I might become dimly aware of a few precedents. (“What other stories have invoked this trope? Because my story is now invoking that lineage, like it or not.”)

I try not to get too hung up on the fact that a trope has appeared; that is, I try not to lock in on it or steer by it. I wouldn’t want to start tidying up or clipping off the story so that it complies with the trope. (I’m always trying to urge a story away from that which I already and readily understand it to be.)

As an example: I was working on the story that would become “A Thing at Work,” in Liberation Day. I had a handful of comic riffs, all set in an office. At one point, a woman I’d named Gen has an awkward interaction in the office kitchen with a co-worker, Brenda. As I was reworking that bit, I found a moment that livened the scene up, or at least it did for me – Brenda insults their boss, who then immediately walks in. Awkward! This leaves Gen feeling implicated – did the boss hear that insult and think that she, Gen, was in on it? Does he now think less of her?

So, she goes down to clear it up with the boss and ends up throwing Brenda – a more working-class person than Gen, several rungs below her on the corporate food chain – under the bus.

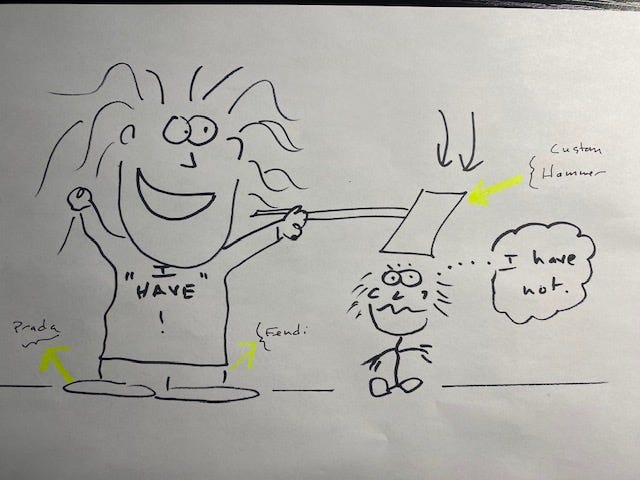

So, I liked this. I recognized “a trope.” (Maybe a better term would be something like “universal human situation seen before in literature”: in this case, something like: “Entitled Have mistreats less fortunate Have-Not.”

And that could be a whole story right there. (In a sense, that’s the arc of “The Overcoat,” which we’ve been working on behind the paywall, or at least the arc of the first three quarters of it.)

But, in this case, a second trope appeared. Turns out, Brenda had something on Gen, namely the fact that Gen had been sneaking away on the company dime, to meet a lover.

So, it seemed natural that Brenda, having been thrown under the bus, would now do the same to Gen, in revenge.

Just like that, a second trope appeared: “Escalating Feud” (joining, to name a few examples, a few of Shakespeare’s history plays, the Grangerfords and Shepherdsons from The Adventures of Huck Finn, a Chekhov story called “Enemies,” a Tobias Wolff story called “The Chain,” and maybe even the early Spielberg movie, Duel).

I’m not claiming, at all, that I overtly recognized any of the above, or thought much about it at the time, or, you know, listed the precedents (I only did that just now, for clarity). I just felt that my story was in a certain tradition and started letting my subconscious shape the story accordingly.

Now, as the questioner very nicely put it, the advantage of having stumbled onto a trope is that a trope comes “with expectations already baked into them which can be played with, subverted, deconstructed, etc.”

For example, when we find ourselves in “Escalating Feud,” we know, approximately, what to expect (more feuding, an eventual confrontation; an explosion or a conditional peace). This gives the writer a chance to do that thing, plus something more – something new, something particular, something that exploits the trope. The reader understands what highway she’s on; that gives us a chance to, let’s say, dictate the exit she takes.

There’s also a way that, once we get a couple of tropes going – in this case, so far (“Entitled Have mistreats less fortunate Have-Not” + “Escalating Feud”), the story immediately starts posing certain questions, such as, in this case: “What happens when there’s an escalating feud between a Have and a Have-Not?” Which, in turn, could become a philosophical/cultural question: “In our country, what happens if a powerful (rich(er), privileged, confident) person gets into a pissing contest with a less fortunate person?”

The beauty of this is that we know the answer (or at least we think we do): the poor person gets screwed. But, because this is a short story and not a PSA, and because it wants to be detail-rich, and involves a specific “fortunate” person and a specific “unfortunate” person, each of them engaging in that feud for her own reasons, we’ll soon find that we’ve written ourselves out of TropeLand and into, well, a story.

So, in “A Thing at Work,” although the unfortunate person, Brenda, does get screwed (she gets fired for stealing – which she, in fact, has done) and the fortunate person, Gen, does indeed walk away pretty much unscathed (except in the mind of the reader who (I hope) has gotten a fresh look at power and the way it works in the world, and who is, mostly but not entirely, on the side of Brenda), the feeling is not so much “Things always happen this way,” but, “In this case, given the parameters, here’s something that could happen”…which, maybe, has the effect of underscoring the variability and multiplicity of our lovely old world.

So, a trope creates general expectations – serving as a kind of booster engine for the reader’s interest (“Ah, I know what story I’m in now”), helping her understand what it is she should be expecting – which then lets the writer individuate that trope into a particular and complex and perhaps even contradictory version/expansion of it.

Similarly with “character tropes” – I never start with one (“I think I’ll do a story on The Prodigal Son” – no, never) but I’ll sometimes find that I have inadvertently made a character who might, at first glance, be an example of a character trope.

As soon as I sense this, I feel glad; glad that I haven’t created a “completely original” character (which might just mean a character unlike anyone who has ever lived, because I haven’t defined her very well – she is, after all, just made out of sentences and may therefore not cohere). So, if a character is an example of a trope, she at least nominally resembles a type of person that really exists in the world.

A second, opposing, feeling I get is: “Careful, she’s a trope!” (If my character stays neatly and obediently within that trope, I will have failed her.)

Are some tropes harmful or biased? Yes, for sure. Tropes are a form of code, of shorthand, and can be lazy. They trim off complexity. If we say someone is, you know, an example of “Forgetful Old Guy” – well, that diminishes that person, by negating all the other things he might be.

A trope might be thought of as an expectation-inducer. If I write a few lines that induce the trope “Spoiled Rich Kid,” you already have some sense of where the story with him in it might go. Likewise with “Nervous Groom” or “Highly Critical Mother-in-Law” or “Nosy Neighbor.” So, that’s good. But left unparticularized, “trope” is very close to “cliché” or “stereotype,” and even “dismissive caricature” (“Right-Wing Nutjob,” “Woke Whiner,” and so on.)

The path from “stereotype” to “character” (from “knowing how we’re supposed to feel about this person” to “feeling blessedly multiple about her”) proceeds by way of increasing specificity of detail. As we follow this path, I’d argue, we are showing our ability to move from (mere) judgment to something like love; we are evidencing our curiosity about, and our patience for, human beings, by consenting to linger a bit, looking for more and more (complicating) detail.

Gen, in my story, was certainly a member of “Snooty Clueless Bosses.” But she was also a person in an open relationship, who flatters herself with New Age platitudes, who finds her stepson too holy for her tastes, someone who, in the end (I think) has some awareness of, and guilt about, what she’s done (even if she’d never admit to this). Brenda is certainly a member of “Victimized Poor,” but she’s also a petty thief, who at different times in the story is judgmental, profane, deluded, and spiteful.

The result (I hope): mixed feelings - mixed valid feelings, i.e., ambiguity.

So, as is so often the case in writing, the technical term of craft – here, “trope” – is a useful descriptor, especially helpful in analysis.

But I absolutely don’t want to be thinking in those terms as I’m doing the thing itself.

I like that increasing the specificity of detail leads directly to “something like love,” in the same way that a sudden understanding of someone I’d thought I hated led directly to empathy.

When I was a kid, I learned how to solve a Rubik's Cube. I can still solve it, but don't have a clue what I'm doing. It just happens because of patterns and muscle memory and enchanted fingers. I couldn't ever teach someone to solve it. The idea of happening upon tropes to set expectations and using those expectations to move the story around is something, I think, I've tried to do, but never realized it. At least I've been more pleased than not when it happens. So, it's quite illuminating, (and validating) when you explain it. Ahah, that's what I'm doing. And why. Great question and answer—thank you both.