Hi everyone,

Am writing this from the road so please forgive any typos, glitches, logical irregularities, and so on.

There’s a funny time lag with these posts - am writing this from the Benjamin Hotel in New York but by the time you read it, I’ll have been to England and then Boston then St. Louis. I wonder how it will all go/will have gone?

Please take what follows as an exploration, not a declaration.

I wanted to briefly take up this idea of darkness, of sad stories. I note, in some of your comments and, for that matter, in the general culture, a desire for “uplifting” stories – stories that are….well, “not so sad,” “hopeful,” “less negative,” etc.

Here’s my theory: the only sad story is a falsified one. What makes a story hopeful, heroic, uplifting, is when the writer has perfectly lived into her story – has responded truthfully to a story’s DNA. She’s not afraid to go where the story leads her. The uplift comes, in a sense, from her fidelity to her task, and from the resulting feeling of honesty in the story, and from the pleasure of watching the artist perform her task with panache, bravery, flair.

The blues are “sad” but are a source of joy if played beautifully; I find Flannery O’Connor’s stories uplifting because they are so damn good – their endings are aware of their beginnings, they never go false, they are joyful in the way they celebrate human brokenness. They make us see that brokenness, which is an uplift – to be trusted like that, by O’Connor. “You are capable of joining me in seeing this,” she seems to say.

We also might think about this question of darkness in terms of the form itself. As we’ve been discussing here, a short story is about (or wants to be about) change. A condition pertains…and that condition changes. Without that change, there’s no story. (“Once upon a time, there was an old woman who lived in Chicago and she just kept living there in the same house in the same way, day after day,” feels like, possibly, the beginning of a story, but not a whole story in itself. We are waiting for something to interrupt that normalcy.)

Now – could we have a story where things are a certain way and then get better, by way of someone’s virtue? I think we could but there would have to be something to push back against. “Bob was a striver. He also worked hard and so he owned ten shops. This made him happy. Being happy made him work even harder, and soon he had twelve shops.” Is this a story? Not yet – somehow it’s not complicated enough. There are no consequences to all of this happiness and striving. Do such people exist? They do, and I’m always happy to meet them. But somehow, until they run into some problems, I’m not sure they belong in a story.

Well, or at least not mine. 😊

(The above example is a slight variation on one in Randall Jarrell’s intro to his “Book of Stories” - one of the strangest and most wonderful unpackings of the “what is a story?” question I’ve ever read.)

But the thing is – all of us run into problems. It’s what humans do.

So, stories tend to be cautionary – they tell us what can go wrong in this life. Here is not a story: “Little Red Riding Hood’s mother had told her not to talk to any wolves she saw in the woods. And so she didn’t.”

As some of you have mentioned, reading many stories in a row might make us long for a “happy” story – one about triumph, say, one in which, at the end, all is well. But when is it, that time when “all is well?”

To my mind, all stories are about triumph. It might just be a question of scale, and of how we define “triumph.” If I am walking along the street in my new suit, holding an expensive vase, and slip and fall into the mud and the vase breaks – that’s just the set-up. That doesn’t say that life always sucks, but just that it sometimes can suck. It says something about the world (“It’s rough down here, brother”), but what happens next? That’s the meaning of the story.

So, in many stories, that change we are looking for is a challenge or a downturn in the fortune of the character. The character is given a chance to rise to an occasion. Things are this way (i.e., normal) and then something goes wrong. But the fact that something goes wrong – or even that things end badly – doesn’t make the story sad, in my view. A character might move toward truth, or come to the end of her rope, or have the scales removed from his eyes. We, as readers, might find ourselves asking, “With what did the character attempt to fight back against the adversity?” Since all of us will face adversity, this is a useful interrogation (“With what resources do I (do we) fight back against adversity?”) But if the writer puts her hands on the scale and gives the character access to resources she would not have access to in real life, this falsification throws the whole experiment off – it’s cynical, a form of cheating.

Talk about “dark,” talk about “sad.” The reader came to us for truth and we gave her bullshit – bromides, false optimism, denial, etc.

Trouble is real in this world but luckily for most of us it doesn’t come every day. We might say that we read stories to prepare ourselves for the coming trouble. Stories, as someone once said, should “comfort the oppressed and oppress the comfortable.” In our time – largely a comfortable time, taken within the context of history – it may be that “oppressing the comfortable” is the preferred mode. The fact that, in stories, the characters may often be in more difficult situations than we are in might be seen as a method of slight exaggeration, that helps us see the oppressed and comfortable portions within ourselves more clearly, as well as helping us see oppression and comfort more clearly in the real world – the way these conditions co-exist and co-enable one another.

I said, a few posts ago, that it’s harder to write a story that praises positive virtues – that shows these virtues in ascendance. I think that’s true. Many an inferior or early-draft story could be summarized like this: “Everything is shit and people suck.” So we should also beware the AutoDarkness. We all know, from experience, that life is a beautiful thing, an amazing gift. We also know that this gift can sometimes explode in our hands – the mind can go bad, circumstances can pile up against us, the body can betray us, and so on. So, stories – especially the trail of stories we leave behind us – might want to represent this complex truth.

I feel, for example, that Delfina, in “Anyone Can Do It,” rises heroically to her situation. She makes a mistake, for reasons with which I sympathize. But she doesn’t despair – we know this from the way she processes the foreman’s actions – she notes them as admirable. She also doesn’t seem to harbor any hatred for Lis – no thoughts of revenge. I believe she will go on, that she’ll deal with things as they come.

Also, the problems in her life have been drawn with such precision. She is a person trying to earn a living, trapped in a marriage from which she is not getting much – not much tenderness. She is doing the best she can, and then she makes a small mistake – the mistake of trusting someone in the same straits she is in, who has given her every reason to trust her. (What Lis does is quite radical - radically crappy. We might wonder how her husband is going to find her? She’s skipped out on her rent, or has left early a place for which she’s already paid. Arguably, Lis has put Kiki at risk by leaving him alone on the porch.)

“Anyone Can Do It,” is a story that lifts me up every time I read it. The fact that a mind as fine and compassionate as Munoz’s exists lifts me up. Delfina’s quiet dignity lifts me up. The perfection of the artistry lifts me up, as does the precision of the descriptions. When I’ve read it, I feel more, not less, able to go out into the world and do what I have to do, with attentiveness and as much love as I can summon up – and the story has given me a boost in love, to take with me.

And this is true of all good stories, regardless of their surficial “happiness” or “sadness.” The writer, writing, might be thought of as a sort of role model. What truly uplifts and inspires us is watching that writer thinking through things, in the form of a story, with empathy and warmth and genuine curiosity — then I feel inspired to try to do the same, in my own work, and also once I’m back out there in the real world.

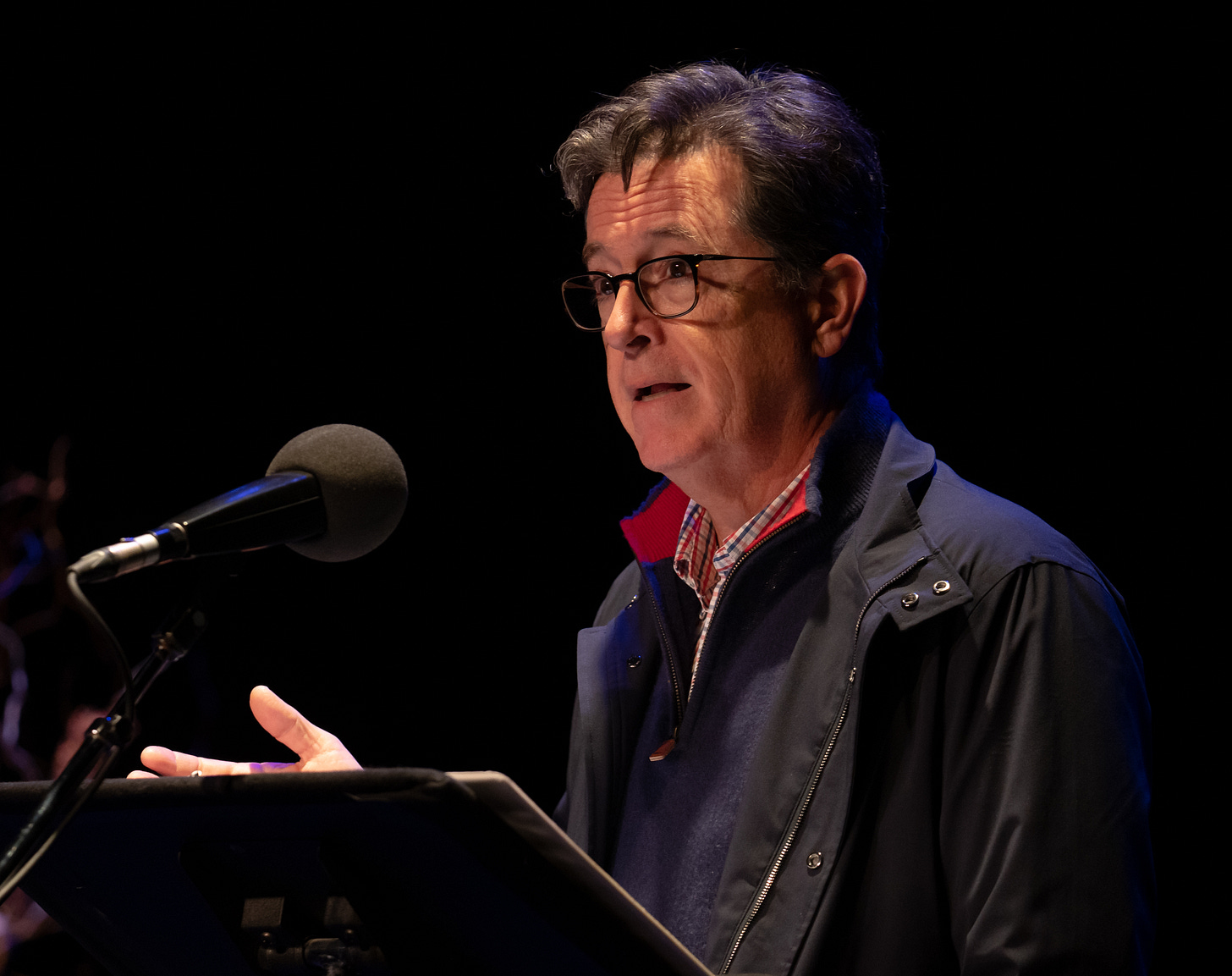

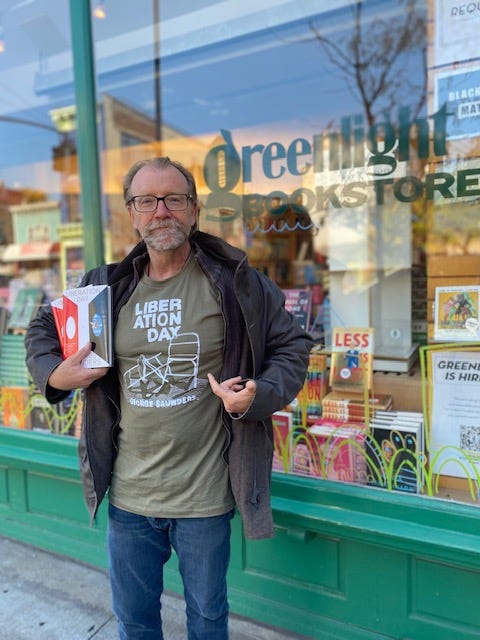

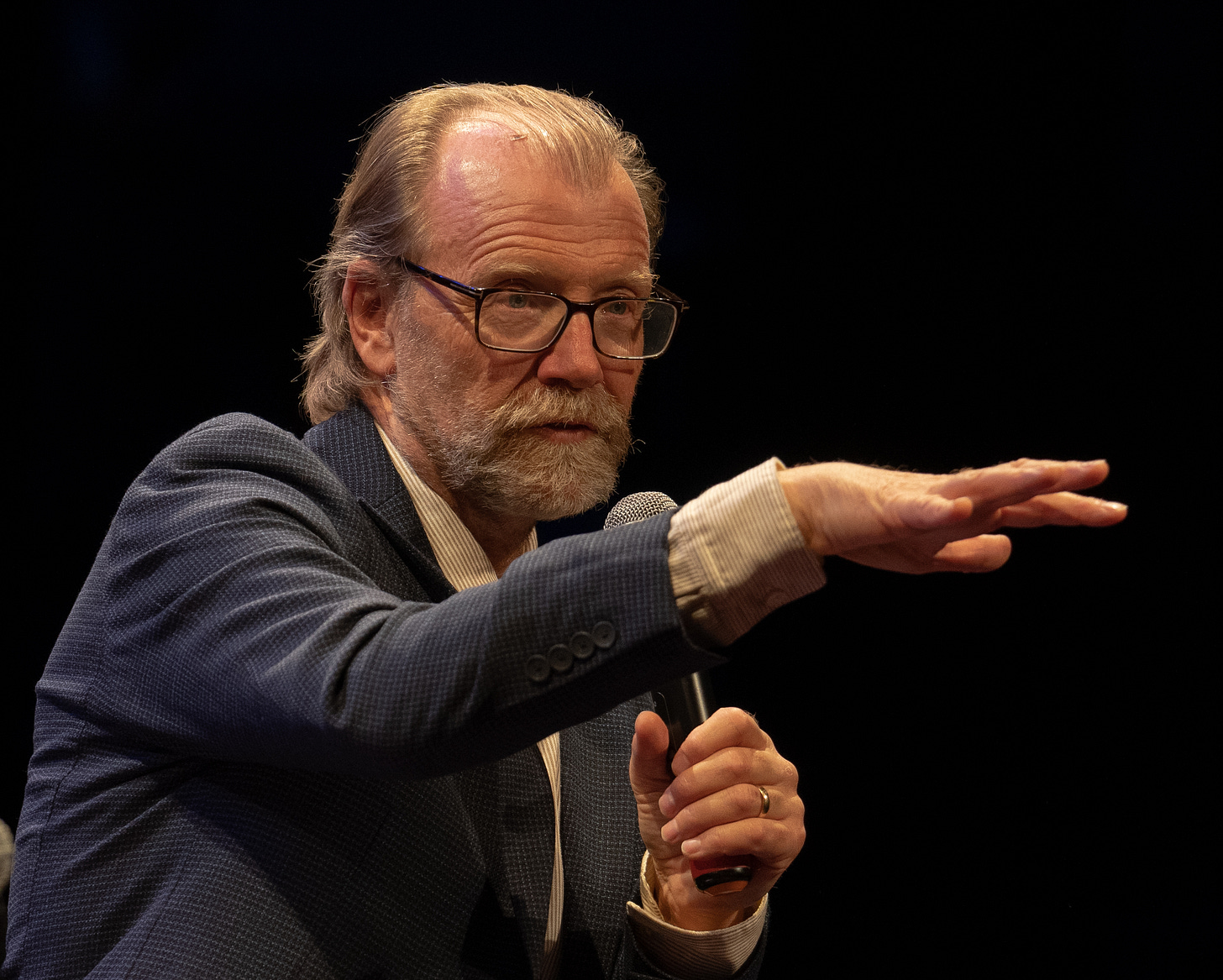

Some pictures from the tour so far, just for fun:

This is me in front of the magnificent Greenlight Books, where I’d just signed books. This store has a special place in my heart because they hosted one of my first events after Tenth of December came out. The illustration on the t-shirt is by our daughter, Alena Saunders, for a company called Out of Print. Thank you, Alena! You can get one here.

Is it okay to say I love you? What a large-hearted person you are. Love the photos. Thank you for sharing! :)

"We might say that we read stories to prepare ourselves for the coming trouble." This--along with the whole "oppress the comfortable" discussion--really resonates, and it also sort of points to the great overlap (has a causal link been demonstrated yet?--I'm a scientist, so I have to ask!) of people who read fiction and people with high levels of empathy/emotional intelligence.