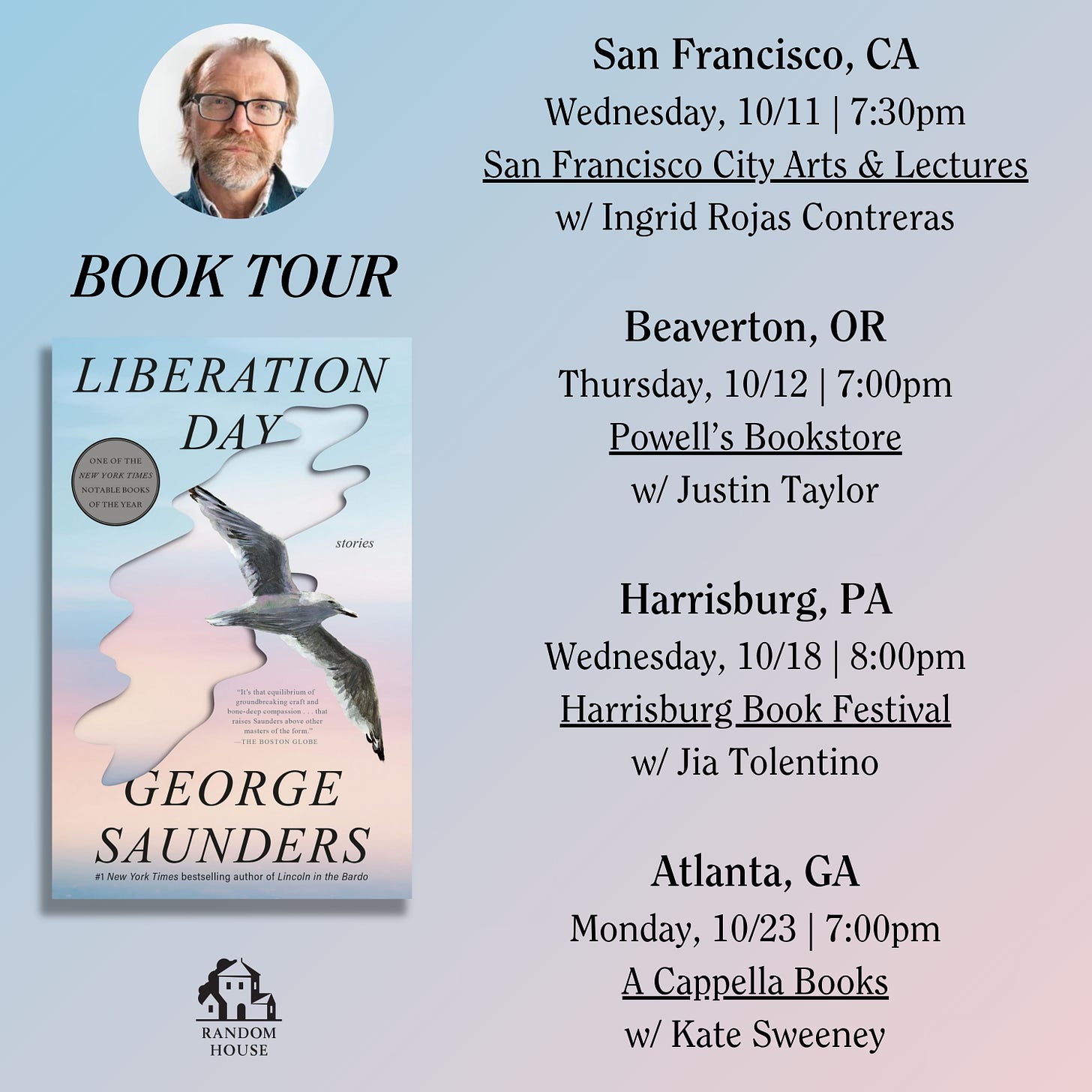

First, before we launch in, a little news on the book-tour front - this is for the paperback of Liberation Day:

You can get directly to the individual venues and to ticketing options here.

I’m also speaking in Lexington, Kentucky, at The University of Kentucky Gaines Center for the Humanities, as part of the 2023 Bale Boone Symposium, “An Evening with George Saunders,” at 6 p.m., Thursday, Oct. 19, in the Kentucky Theatre.

Hope to see some of you out there.

Second, I was recently a guest on Ben Arthur’s phenomenal podcast SongWriter, in which Ben and Craig Finn of The Hold Steady take on my story “Sea Oak.”

Here’s an article about the episode in Paste….

…and here’s the episode itself.

Thanks to Ben and Craig for all their artistry and effort (and to the incredibly gifted Vienna Teng, who sings backup on Ben’s song).

Now, for our question of the week:

Q.

Thanks for the opportunity to think and ask...

I do have a question about humour.

You're funny in your stories and in your blog (where it's sometimes, you know, Bathos, and sometimes just that pleasure in the jump from written convention to pseudo-transcription of a spoken presence, and sometimes just a funny thing to say, or even just a gentle warmth).

When my partner makes me laugh, it's the spontaneity of it that delights. But when a performer hits it, there's often a bounce then a second laugh of pure joy at the illusion of spontaneity, or rather a recognition at the craft of it, perhaps a micro-pause or an inflection shifted a hemi-semi-tone, just enough to be surprising but not too much to seem forced or designed. A facility for connecting rhythm, form and sense, I suppose you might say... which doesn't seem far off poetry.

When I first read them, I was surprised to discover that Tolstoy could be funny, that Chekov could be very funny, even though at school I had already been surprised when Dickens made me laugh out loud. These Great Artists were, I found, not completely overwhelmed by their own greatness, but could make me laugh, could be warm and show love through humour.

I just wonder how humour comes out of your writing process, how it connects to your funny spontaneous self, how it connects you to humanity and how you respond to humour in the writers you have so generously shared with us so far?

Thank you again.

A.

And thank you, for this question.

Funny is, of course, hard to talk about.

I think 1) a person is either inclined to use humor or isn’t (and that’s likely related to how he or she is in-person), and 2) it’s useful, for me, to think of humor as more by-product than goal.

To point (1): I’ve always been funny, or at least tried to be. My first girlfriend pulled me aside to tell me she was thinking of breaking up with me because I was always making jokes about everything. In response, of course, I made a joke.

End of relationship.

But I’ve always turned to (resorted to) humor at moments of tension or happiness or tragedy or anxiety in my life. I’m not sure that’s a good trait….but it’s one I have. And I only started to have any luck as a writer when I succumbed to it/welcomed it.

To point (2): I find it really hard to be funny when I’m thinking, “Come on, be funny!” Most of the funny moments in my writing come out of reaction – that is, I’ll be re-reading something I’ve written and a moment in there will produce an instantaneous response in my mind – an idea of something to add (or, sometimes, to cut), some specific words, or a funny direction in which to take the riff - that sort of thing.

I read a bit at-speed and…something occurs to me.

So, I put it in (knowing that I may very well take it out next time through if it’s suddenly not funny anymore).

This way of thinking about humor (as reaction), takes the pressure off. I’m not trying to be funny. I’m even trying not to be funny.

But then, here comes a moment, and I can’t help but react.

It’s kind of like…you’re standing in a park, and here comes a Frisbee. It seems possible that you could catch it.

Why not try?

Of course, a person must have a goofy/unusual/irreverent/zany attitude toward life for those reactions to arise in the first place.

(As I’ve said here before, we find out who we are, by way of those reactions.)

I’ve always felt humor as a joyful thing, likely because of my family. On both sides (I have a Chicago side and an Amarillo, Texas, side) we had really funny people who could light up a room by being funny. I came, very early, to see being funny as a form of being powerful, and of being generous - able to give the gift of making a moment incrementally better, or of suddenly relaxing everyone and making them glad to be alive.

For me, humor comes out of this notion: life is one thing, and our approach to it often pretends that it’s something else – something tidier and more in our control. When life reminds us that it is not tidy, and is not in our control…that’s funny. It’s the truth, startling us, coming at us a little more abruptly than usual, even rudely: “Life is not what you think it is.”

Which is another way of saying: “Your mind is limited, compared to the universe. Get over yourself and your need to be sure, correct, and always in triumph.”

Somewhere deep down, we know that — we know that life is not tidy and not in our control — and are always desperately trying to forget it.

And then…we’re reminded.

Funny.

I remember getting an early lesson in humor. In high school I was in an English class taught by a wonderful teacher named Sheri Williams. She was really funny herself, very cool and welcoming – but ran a tight ship. She expected us to be prepared and respectful - to her, to one another, to the literature we were reading. She loved fiction and was an incredibly effective advocate for it. When she talked about writing and writers, she made it clear why literature mattered, why it was needed and relevant, even to us teenagers.

Of course, we adored her.

I wasn’t much of a student, but her personal power was undeniable, as was her commitment to us, and this always made me want to impress her, be noticed by her.

Along the way, I noticed this: if a kid made a joke in class, and it was a good one, she’d laugh, which was great – the best, actually.

But if you interrupted her flow with a dumb joke – not great.

Painful, even.

But a terrific comedy workshop.

I learned, right away, that if I “planned” a joke, or allowed even a few extra micro-seconds for vetting (asking “Is this funny enough to risk failure?”), the joke would flop, doomed by overdetermination.

By experimenting, I found that the “good” jokes I managed to make always felt, as I delivered them, kind of the same. They were spontaneous – there was literally no time between conception and delivery. The process was: a thought appears….I can’t not say this….There, I said it….Hooray it worked…Ms. Williams is smiling.

Although, truthfully, that isn’t quite accurate. Sometimes, following the above plan, I’d just blurt something out…and it would flop. And I’d realize (there among the cricket sounds) that, in fact, there was, in the “no pause between conception and delivery” model, a slight, very slight, vetting step, that took the briefest millisecond but was essential.

Failing was….uncomfortable. I remember, even now, the pitying look Ms. Williams would shoot my way, as in: “George, really? I like you, but that joke….no.” Her reaction wasn’t harsh (there was actually a lot of affection in it); but it brought about an honest, mutual acknowledgement of bombage. Which, given how much I respected her, was enough.

And I’d vow to myself never to risk a joke in there again.

Until the next time a chance arose…

For me, the lesson in all of this was that “being funny” was all about the feelings I was having during the process. It was not about “theory of funny.” There was no consistent approach that would guarantee a laugh. You had to be there, in that moment. And then (instantaneously) decide. It was about the doing, and you’d know if you were doing it right by the reaction you got.

Period.

It’s similar on the page, now. Funny or not is a matter of split-second judgement, not planning or theory or willpower.

Isaac Babel, writing about style in his great story “De Maupassant” (a story I hope we’ll take up soon here) said:

“A phrase is born into the world both good and bad at the same time. The secret lies in a slight, an almost invisible twist. The lever should rest in your hand, getting warm, and you can only turn it once, not twice.”

This is absolutely true for humor.

If I’m reading along and have a genuine, spontaneous reaction to my text (an unplanned, unvetted, unrationalized reaction)…that’s good. I trust that. If there’s any quality of predetermination, that joke will likely end up getting cut later.

And this, of course, is also true for “non-funny” reactions. If we reading and come across, say, a physical description, and have a reaction, we can use that too:

The sun was red.

We read this and…we react…and something inclines us to tweak it as follows:

The red sun was turning the white sand pink.

Is that better? Well, I’ll decide that next time I read through it, sharp pencil in hand.

But that change was my reaction in the moment. (This time.)

There’s also the question of how to be funny when writing new text/approaching the blank page.

But it’s interesting. Except at the very beginning, there never really is a blank page. We always have something to react to, if only the previous image or phrase.

Or sometimes it might be an element of the story that, having put in there, has to bloom. (In “Sea Oak,” once I had one part of Bernie fall of, other parts had to fall off as well, which, while sad, was also funny - in part because the reader had been prepared for it by the early falling-off part.)

In general, my preset is to try to tell things relatively straight at first. I’m mostly trying to find the next solid bit of communication: an action, a movement, a line of dialogue. This keeps the story moving ahead.

But it also gives me something to be funny about, or funny with, if the story seems to want to go in that direction.

This way, the humor, if it appears, will feel natural and earned, rather than forced on the story and contrived. It will appear organically – which tends to make it funnier. (The reader feels the need for the joke just as it’s delivered.)

In other words, my flavor of humor seems to work best when I make the funny bits earn their way in.

Sometimes, being funny is just noting something that is already funnyish in the text: an ambient tone, a joke waiting to be made, an inadvertent quality in the prose that both I and the reader are in the process of noting. The “funny” happens when I turn to the reader and acknowledge that thing.

Say I write:

I was waiting for Lois. In my car. She was inside. In the store.

Well, something about that is….being noticed by me: the laconic tone, the short sentences.

So, I feel like reacting to that – acknowledging to the reader what we are both already subtly noticing about the tone.

I was waiting for Lois. In my car. She was inside. In the store. Across the street. Prince Street. Jeez, I thought. To myself. What gives? Why so brisk? Minimal. Understated. Ah yes: Lois, had taped my mouth shut. Before she went it. She always did. Lois. She cracked me up. But I. Was running out. Of air. The tape over my mouth was messing. With. My. Breathing. Long sentences? No. None. Cannot.

OK, well, not that funny – but you get the idea.

Any swath of prose has ambient qualities. Calling those into the open is one form of humor.

Just as, in that long-ago classroom, I was trying to react to the mood in the room, when writing, we are trying to react to the mood of the prose.

And here I find I’ve exhausted myself by trying to make this thing more rational than it could ever be. And I haven’t even talked about, for example, what makes a story’s set-up inherently funny, and the philosophical ramifications of that. Or when I’ll sacrifice a bit of funny, in the name of seriousness. Or the Zen practice of choosing the better version of two jokes that are really the same joke and are in the same story.

It makes me feel a little queasy, honestly, trying to reduce humor like this.

Because being funny is a mystery. And should remain so.

No joke.

Humor really is one of the greatest signs of intelligence. I struggle with stories that contain no humor; I don't feel traumatic passages as deeply if the author never gives me a chance to come up for air.

Long ago I was a reader for The Crescent Review, a literary magazine, long gone, out of North Carolina, I think. The editor, whose name I don't remember, gave me instructions, one of them about humor: if a story is funny, send it on to me. We don't get enough humor.

I'd agree with that. Not enough by way of story in contemporary America is funny. Talk about Chekhov being funny, though his plays are sometimes done dead serious. It's his own sense of humor. Tolstoy, yes, the moralist. Dostoevsky too can be funny, funnier, I think, even in those long, serious novels. Dmitri is just about to make love to Grushenka when he's arrested. Painfully funny. But I do think humor is a function of the personality of the writer. If it's not there, it's not going to make its way into a story. If it IS there, it will get into your first draft, at least. And I think it ought to be nurtured. Laughter heals.