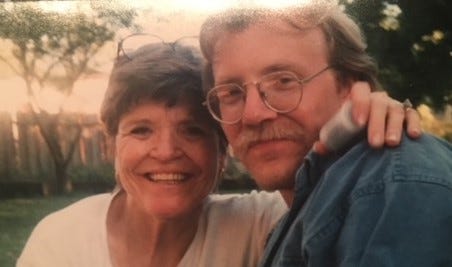

Happy Mother’s Day, and sending lots of love to my mother, Joan Saunders, the dearest heart on the planet, who has been taking sublime care of me since 1958.

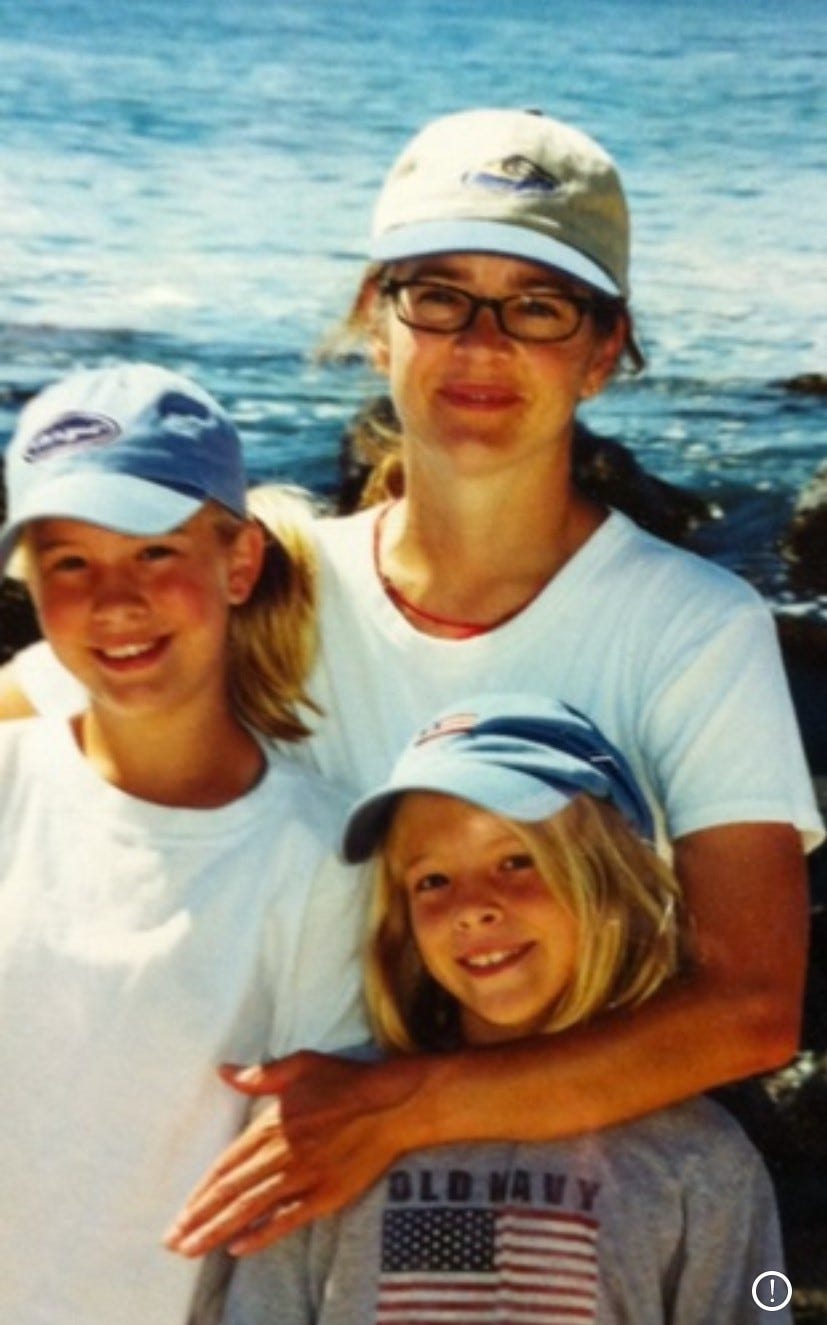

And my deepest love and appreciation to my dear Paula, for being such a magnificent mother and role model to our daughters.

I’ve often thought that our first scale-model of the universe comes to us by way of our mother’s attitude toward us. “Does it like me? Will it be nice to me? Am I o.k.? Is it all right to take some chances out there?”

I was so lucky in this regard, as were our kids.

Anyway, here’s to all of the mothers out there, and all of the grand- and great-grandmothers, and all of the kids and…well, here’s to everybody, and to love and nurturing in all its forms…and Happy Mother’s Day.

Last time I asked you to read “The Snowstorm” and “Master and Man” back-to-back, and discuss the differences between the two versions, which you’ve done admirably in the Comments.

I examined the Chaplin clips and these two stories in Afterthought #6 of A Swim in a Pond in the Rain and came up with some general conclusions; I concluded that the more highly organized systems (the fight scene in City Lights, and “Master and Man,” according to me) had more pronounced and intentional causation. The elements seem to have been more precisely selected. The escalation is more decisive, everything seems more to purpose. At all times, it seems, the story is posing a question, and we know, roughly, what it is. Expectations are arising and the story is, if not addressing them, taking them into account. We feel in connection with the author, who seems to “see” us - to know where we are at each moment.

The question for those of us doing artistic work is: what do I do, to get my system to be more highly organized in this way?

By the way — I’m also aware that some of you, in the Comments, have expressed a preference for the fight scene in “The Champion,” i.e., the one I consider less organized and…not as good. To which I say: Fair enough! That’s the real value in this sort of discussion: having one’s feet put to the fire re. the question: “What do I really value in a work of art?” (Or, you know, putting one’s own feet to the fire). There is literally no wrong answer. The value lies in clarifying one’s preferences, asking, with ever-increasing intensity and honesty: “What do I like? And why?”

We might also bring up here the concept of wabi-sabi – the idea that some degree of looseness and imperfection is desirable in a work of art, if only to mimic the looseness and imperfection of real life. One of the dangers of overworking something is that it can come to feel, well…overworked: the reader/viewer may feel left out of the process, as if the artist was performing for himself or herself only. The reader/viewer may feel that the creator is so obsessed with asserting artistic control (with efficiency, with clarity, with cause-and-effect) that this sort of control has become the work’s whole reason for existence - a rather condescending stance, that is more about power and less about communication.

So, as is the case with so many things in art, it comes down to a turn of the dial. What is polished enough for you? What does it feel like, to you, when you’ve blundered into Too Tightly Controlled Land? What, on the other hand, does it feel like when you haven’t revised enough?

There are, of course, many names for what I’m calling “a more highly organized system.” We’re really talking, I suppose, about the arc a work of art might follow as it progresses from “early and blurry” to “polished and precise.” But even those word pairs are iffy; a given artist might characterize that journey differently. (She might feel that her work progresses from “cold and intellectual” to “personal and heartfelt,” for example.)

This is all very personal, idiosyncratic stuff. We are always trying to find a language to use in talking about our work, but that language is necessarily imperfect and imprecise (and may, in the end, after all, only apply to our work).

There’s this thing called “art,” and there must be things that are true about it; there’s this thing called “process” and lord knows we talk about it enough.

But it’s a little like that old parable about the three blind men and the elephant which, if I remember it correctly, goes something like this:

One blind man grabs the tail and says, “An elephant is like a rope.” The second grabs the tusk and says, “An elephant is like a tree trunk.” The third grabs the trunk and says, “An elephant is like a big snake.” They are all right, in their own way, but the “truth” of the elephant is bigger than these limited individual observations. (To see the elephant, all at once, in its entirety, would be nice, and would eliminate the need for all the reductive, partial attempts at description.) There is, at some exalted level, I suppose, only one truth about art - a beautiful work of art is manifesting one uber-quality, ultimately, for which there is no name — but, like those three blind men, we can only intuit portions of that great quality, and so have to blunder around, partially describing art and its associated processes.

I suppose we come closest to that one truth when we’re writing well - at that moment, worldlessly, we’re inside that truth, living in it, being it, honoring it, not worried about describing its qualities.

So, a beautiful work of art has certain qualities, for sure, and these qualities can be named and discussed in an infinite number of ways, none of which is authoritative or entirely sufficient. What we are trying to do, I suppose, is succeed in naming them in our way – in a way that will be useful to us.

Most important of all, we are trying to develop those habits of practice that lead our systems along the path toward “better” – “better” by our definition of it, which we don’t have to articulate or defend.

One way of approaching this notion is to read the best story (or passage) you’ve ever written, then read something of yours that you feel is definitely less good.

Just screw your courage to the sticking place, sit down, and read the two pieces, as if someone else had written them. See what the best story has that the lesser one lacks. (Or, rather than “seeing” this, we might aspire to “feeling” it.)

My contention is that the juxtaposition itself — with no attempt to speak about the process or diagnose or draw conclusions or resolve to do this or refrain from doing that — is valuable, in and of itself; there’s real value in that visceral moment of contrast.

I do a version of this all the time when writing. At this stage of my working life, the “better” or “polished” or “sufficiently revised” model of my prose sort of exists in my mind, continuously. And when, on a given day, I reluctantly pull a draft-in-progress toward me across the desk and start reading, that model of “finished prose” is invoked and begins hovering over the work in progress.

As I start reading, I feel…discontent, first of all. Discontent with the unformed quality of the draft-in-progress. There’s not much thinking or analysis going on – it’s just a feeling of impatience with the draft, like: “Ugh, how could you/how dare you?” I can feel in my gut the shortfall in the level of completeness or polish or revision-gleam and intelligence and heart between my “finished prose” model and the thing I’m working on. So, the draft-in-progress makes me feel antsy. And vulnerable. I get a little panicked at the thought that this version might somehow makes its way out into the world. This then translates into a feeling of resolve and even relief: it’s not been sent out yet, so I can still make it better. Then there’s a feeling of being suddenly willing to bring more intense tools to bear. I become willing to try more radical cuts and rearrangements, to lose the treasured bits, the gems. All of my extant, self-congratulatory aesthetic ideas about the piece and its virtues get called rather rudely into question. These ideas are felt as a form of fearful scaffolding; they suddenly feel placeholderish and timid, like a sort of ceiling that I have, in my insecurity, placed on the work.

And then…for all of the negativity and self-remonstrating in the above, there’s a feeling of freshness, a feeling that the only way this sucky thing could become part of my life’s work is if I get lazy about it — which is, I guess, a form of hope: the path that leads from “what this is” to “what it could be” is going to require a lot of hard work…but I am suddenly up for it and see it as an opportunity to…well, to not suck.

And none of this is conceptual. There are no “notes to self” re how to do anything, or what to embrace or avoid1. There are no maxims, no attempts to decide anything. All that’s been accomplished is a renewed sense of urgency. I may not know what the finished product is going to sound like, or be about, or what, exactly, will be needed to get it to where it wants to be, but I know, at least, that this thing in front of me is not going to cut it.

I have sort of cornered myself, via my good taste, ha ha.

It’s like looking around one’s messy house three days before a party vs. thirty minutes before. My memory of what my “finished prose” sounds like is analogous to a photo of that house at its very best – something to aspire to. And - most of all - something to get busy on, pronto, with renewed energy. (Samuel Johnson: “Depend upon it, Sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.“)

And, in a spirit of honest self-assessment: I feel that one of my gifts as a writer is an endless appetite for the process described above - a craving for it, actually.

Although, to be a tad more honest, there might be a few loose ideas: “the middle is baggy,” or “it falls apart after page 4” or “cut it all but the part about the moving van.”

Happy Mother’s Day, to all of us. My own mother is dead and gone, and so I also want to give a shout out to those of us who have lost our mothers or those for whom motherhood wasn’t possible or chosen, or those who once had children and no longer have them. It’s a beautiful day but can also be a tough one. Peace and love to all of you.

George writes: "There is literally no wrong answer. The value lies in clarifying one’s preferences, asking, with ever-increasing intensity and honesty: “What do I like? And why?”"

But in order to get to this point—to the point when you can ask yourself “what do I like and why?”—takes a self-confidence, trust, and the ability to not care what others may think—and that’s not always easy. It’s also, surprisingly, not always easy to form a clear opinion in the first place, to know what you like or don’t like, as your true feelings can often become obscured by an overlay of feelings and thoughts disconnected from your visceral self. We are so overwhelmed by what the world tells us to think! And our own personal biases and histories can get in the way so much that we don’t recognize art when we see it, or our own feelings when we feel them. And then we read and learn about art so that we feel safer about making assumptions and having opinions—and that education can get in the way, too! Being told what is “good art” isn’t always helpful! Then again, who wants to fall in love with something only to find out later that the rest of the world finds it trite and worthless? That sense of humiliation, to realize you’ve missed something that the cognoscenti know—it’s not a good feeling. To have real clarity about your own likes and dislikes—it’s hard, but worth striving for.

Elsewhere, George has written this: “It’s kind of crazy, but, in my experience, that’s the whole game: 1) becoming convinced that there is a voice inside you that really, really knows what it likes, and 2) getting better at hearing that voice and acting on its behalf.”

Here, “number two” is where the hang up is. Even if you've gotten better at locating that voice inside of you, the true voice that can separate itself from all of the world that is screaming at you and telling you what to think, there may still still be a problem with “…and acting on its behalf.” Yes, that is the goal. But good luck with "acting on its behalf." That’s where the mystery is. We can use that dial in our brain that George talks about (negative/positive) and (probably) see that much of what we’ve written falls on the “negative” side. But to fix it—that’s the rub. George writes of using one’s intuition, which is akin to listening to that voice in your head. But for beginners, that may mean hundreds of attempts, over and over again. Listening, and then realizing you were wrong. Listening again. It’s daunting. It’s exhausting. Many people never try at all and many who do try, give up.

“I have sort of cornered myself, via my good taste, ha ha.” Love that!

The message, to me, from George’s post this week is: Trust yourself. But more than that, the message is: Keep going.

"I’ve often thought that our first scale-model of the universe comes to us by way of our mother’s attitude toward us. 'Does it like me? Will it be nice to me? Am I o.k.? Is it all right to take some chances out there?'”

And here's to those of us who haven't read the rest of this email yet because we close the window every time we reach this paragraph.