Hi George,

If I enumerated the ways Story Club has altered my life for the better, we'd be here all week—and I’ve got to save some energy to fight for democracy—so for now, I’ll just say thank you.

My question is about time. Not in literature, but in life.

I’m a playwright. In former incarnations, I was also (always) a "high achiever" type. I’m working with your process these days, and I have to say, though some days I find myself getting so fiddly with a bit of dialogue that I want to throw my computer out the window and go back to my old "automatic writing" ways, mostly, I'm sold. Writing feels more accessible, weird, intuitive, and joyful than ever before. I find myself getting closer to my own "voice"—which has felt ever elusive until now.

That said.

I struggle a lot with impatience. I struggle with very strong conditioning that tells me I should be "productive" in concrete, measurable ways (words/pages written, for example). Fiddling with "blops" (great word, btw) for weeks on end feels counter to this conditioning. My critical mind can come in, as it did this Monday when I read my latest draft, and say harshly—"this is self-indulgent, you need to be outlining, you need to figure out what the hell the story is here, you need to exert more control over things." In other words: I'm freaking out about how long you're taking on this.

Now, when I actually look back over the past few years with some distance, it isn’t true that my old processes yielded more productivity. I mean, maybe I collected more total blops, but that doesn’t mean they cohered into finished plays. And this time around, the truth is I got to something resembling a first draft more quickly than I ever have (and, incidentally, the part that’s most terrible is the part where I did let my impatience infiltrate the process and decided to "just write through to the end").

But I guess my question is: how do you deal with this, if it happens to you? Impatience with how long things take, with a thing not yet being a story? Does it lead you to question whether there’s a failure of process? Whether you need to exert more control? How do you handle that in the moment?

And I guess, relatedly, what about worldly things like planning and deadlines? I imagine you can’t avoid them entirely, given, you know, capitalism. What happens when you get an assignment or a deadline—how does the process adapt to that? And when you’re not working under any kind of deadline, how do you judge whether you've done a good day’s (or week’s) work? How do you hold yourself to some kind of bar (so as not to give in entirely to entropy, doom scrolling, reorganizing bookshelves...) when the yardstick you’re using on a daily basis is different from our product-obsessed culture's yardsticks?

Okay—thanks so much. I guess that was a lot of questions, but hopefully they’re all circling around the same core question...

With endless gratitude,

A.

Aw, thanks so much for the first paragraph and I hope all of you know how much you enrich my life too.

It’s a good thing we’ve got going here.

First, I don’t usually have deadlines for my fiction. Sometimes there are deadlines in turning around edits and so on. But in terms of starting and finishing a story or book, all my deadlines are internal – which, in some ways, makes things harder, and intensifies the struggle you mention above. (If I can work on something forever…oh God, I might end up working on something forever.)

So, yes, these are all good questions and are, I think, all part of the same big question, which has to do with the fact that we want to do good work, at the right pace – we don’t want to flounder or drift or delude ourselves about the quality of what we’re doing - but the clock that measures “real” artistic progress isn’t always in sync with our normal ways of measuring progress (hours spent, total words; how we “feel about” the day’s work).

I absolutely do know what you mean here. There can be days or weeks or months where I’m thinking, “Dear Lord, please just show me that I have a story here and, if you would, what the heck it is, so that I can feel justified in going on.” This is part of that syndrome wherein we artists are willing to walk through flames just as long as we can be assured that the whole escapade is going to lead is to something good.

Sadly, that guarantee is not available in the land of art.

Before I leap in, I want to comment on one sentence of your question, namely:

“The part that’s most terrible is the part where I did let my impatience infiltrate the process and decided to ‘just write through to the end.’”

I just want to say, in the name of honesty, that I do this too, all the time. I also revert to what you call “automatic writing” – just going with a riff or an impulse. It is not, for me, I promise, just endless slow fussing with phrases: for sure not.

There are many ways to get a text, and all are fair game. (And I mean all.)

Or, to say it another way: I write every way there is to write: fast, slow, considered, wild-assed, neurotically, logically. You name it. One indication of a healthy artistic practice is a certain inconsistency of approach. We do this, we do that, some of it works, some doesn’t, and so on.

This can be proof, maybe, that we’re not on AutoPilot.

The only proviso is that I don’t necessarily trust what I burst out, no matter how I burst it out: everything has to submit to revision, no matter how it was produced.

But, for me, editing is the all-purpose friend that protects me. 😊

(Sometimes that “editing” is just reading what I’ve written and approving it (a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph) but that, too, is editing.)

When we talk about artistic patience, we’re really talking about the question, “How long do I stick with this thing before I give it up?” Which is another way of asking, “Are they some ideas that are just bad/unfinishable?”

I get this question so often that I am quite sure it can’t be answered except through the individual artist’s experience.

But….

In last Thursday’s post, I wrote this:

“For most writers, I think, it’s best to assume that if your subconscious gave you something, that thing can be finished, and wants to be. (Although, there’s a whole world in the phrase “if your subconscious gave you something.” Sometimes it hasn’t but we think it has. Maybe a topic for another time).”

And then Fred V. asked if I would elaborate on that idea. Now, since we’re discussing artistic patience, it seems like a good time for that.

How do we tell a “good” idea that our subconscious gives us, from a “bad” one? Like the old joke about how to get to Carnegie Hall, the answer is, “Practice, practice.”

For me, it’s a feeling. An idea arrives wrapped in a certain feeling, and I think, “No, you don’t.” In a different feeling, I think, “Huh, maybe.” And so on.

Generally, if something comes to me and I give it a try, and get some good paragraphs out of it, after editing – if they attain a sort of solidity or undeniability that I identify with my prose at its best – then I just say to myself, “Someday, this is going to turn into something.” And I leave it at that and will never abandon it.

And that attitude amounts to, or produces, infinite patience.

If even one paragraph has those qualities mentioned above (solidity, undeniability), then that bit becomes like a foundation stone for the rest of the story. Suddenly, I can hear and feel the difference between the “good” (solid, undeniable) prose and…the rest.

I’m drifting off this topic of patience a bit….although I’m really trying to suggest how we might get more of it. I’m saying that “patience” is what we have toward something we are considering quitting. But, if giving up on a piece is disallowed, what would “patience” even mean?

If, instead, we view a work-in-progress as something that wants to solve itself and just needs time – as much time as it needs – then our role becomes attending to it, no matter what – rather than, you know, standing there with a stopwatch, going, “Hello, my career, if you please.”

Sometimes I just think, “to” a piece in-progress: “Hey, you are really pretty good, but we seem to be unsure of how you want to progress - mind if I set you aside for awhile? You sit there, for a month or a year, continuing to be just as good as you are, and someday….” And off I go, to something else.

As Rodin said: “Patience, too, is an exertion of energy.”

But: (disclaimer): it wasn’t always this way for me. When younger, I abandoned, and rightly so, loads of things. The change came, I think, around the first time I felt like I hit my stride, just in terms of getting my prose to attain that “solidity and undeniability” mentioned above.

This approach gets easier after you’ve broken the code even once. That is, once this method of editing has worked for you – you’ll never go back. (I’m exaggerating a little for effect here, by the way). But: once this method has yielded some writing that you’re proud of (or a story that works) you’ll find yourself waiting for that thing to happen again; you’ll feel dissatisfied to find yourself still in the land below that peak experience, if you will.

These days, I will work for months or even years, pretty sure that, eventually, something will rise out of the mess. Which is a comfort, since the takeaway is: keep grinding, in faith and with hope.

And if this method isn’t for you, you’ll know it eventually, by the morass you find yourself getting into. I joke, and yet not. The longer I do Story Club the less confidence I have that advice from one writer is neatly exportable. What I’m trying to say here (always) is, “Maybe try this?” and I am very happy if the answer is: “I did. No good. Not for me, anyway.”

When I find myself lost in a story that seems like it will never congeal, I try to remember two things.

One is something Toni Morrison said, regarding her novels – as I recall it, she said that they often began with a long period of digging out a foundation, and that her experience was that the deeper the foundation, the stronger and taller (better, more complex) the resulting structure.

Second: the only real metric is, “Did I write a beautiful story?” If it takes me three years to write a beautiful story, well…I did it. I have that story. If I get impatient, and give up, or I write in a hurried, too-results-oriented way, that doesn’t result in a beautiful story….I lost all that time. And I’ve got nothing to show for it.

Maybe the only way to judge whether we’re spending our time well in our work is to look at what we’re doing during that time. Are we reading the text well? Considering all possible changes? Is our mind alert to the text? Are we being brave? Are we stumbling into any newness? And so on.

In some ways, I suppose, it’s not so unlike life itself. What is a day well-spent? I’d say, if I’m really being honest, it’s a day spent in the right mental state (alert, loving, open, etc.) Same with writing. We can’t guarantee results, but we can try to be there at the desk, aware of the state of our mind, enjoying it, in our way, even when it’s “not going well.” In a weird way, if we recognize “not going well” as a part of the process, suddenly…things are going just fine.

Speaking of which…

The other day, in the comments, someone mentioned that, for him, writing wasn’t (as it seemed to be for me, he said) much “fun.”

And I feel compelled to clarify what I mean by “fun” when I use that word in this context.

I’m not sitting at my desk grinning and laughing, racing down overjoyed to get coffee, stopping contentedly to hear the birds singing, pausing to say a prayer of gratitude that I’m allowed to be an artist, etc. Ha ha, no. It’s very much a grind. Anxiety about whether the thing is good, irritation at interruptions, frustration when I’ve tried something and it hasn’t worked, and so on. Lots of doubts about whether I can finish, whether the result will be good (whether (see above) I’m wasting my time). But the feeling of making progress is “fun.” Those moments when something suddenly reveals itself: “fun.” The knowledge that all of my self-doubt and doubts about the story are not mistakes; they are integral parts of the process and, in a weird way, knowing that is “fun.”

So: an enjoyable grind.

I think I emphasize “fun” just because I get better results if I try to think of my work as fun, a privilege, a blast, something deep, etc. – as opposed to feeling put upon by it. There’s a mythology of the suffering writer (if you’re not miserable while you’re doing it, it can’t be good) that I like to poke at now and then.

But, on the other hand: if feeling put upon (or dreading it, or resisting it, or feeling depressed by it all) gets good results for you, then I am for that, 100 percent. (And that’s how it is for me too, sometimes.)

So much of talking about craft comes out of the desire to put it all to rest, once and for all – to just have a method that we use over and over, without needing to think about it. But this is exactly anti-art. To be an artist means, really means, coming to the desk like a goofball every day, knowing little or nothing but game to try, equipped only with that day’s sense of what is beautiful.

As always, very much looking forward to receiving the wisdom of the group.

I posted this on Sunday for our (beloved, treasured) Paid subscribers, just reposting here for any of you who might be in London or art lovers:

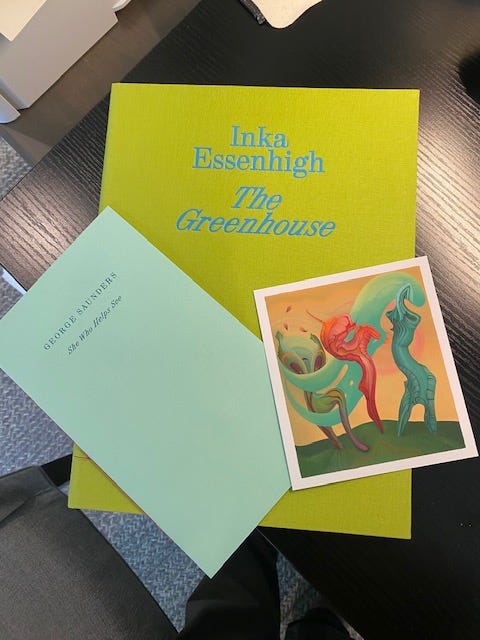

I recently had the pleasure of writing about the work of the wonderful artist Inka Essenhigh, whose new show, “The Greenhouse,” is at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London, March 14 - April 17. The Paris Review was kind enough to publish an excerpt this week.

I am not a famous writer, nor do I hope to be one. (This sounds like Emily D.) I am awed by George's works, and the writing shared in Story Club.

Like others in my writing group, I write for the joy of writing. But never is that an especially fun venture. I enjoy those days when my prose flows, I get a draft half or entirely done, and I get to spend days and days and more revising. I love the intensity I find in revision. Recently my little sister died, and I am bereft. She's always been my first reader. Writing about her these days hasn't helped to heal my heart. Revision strangely does help. Centers, focuses me. For hours. And gives me the grace--of staying in the moment, being fully present. That grace is beginning to heal me.

If I know one thing it's this. When you're writing, don't boss it around. Pretty simple.