So, we’re done and by now you will have reacted to that “real” ending.

One thing we often talk about in class (and which has also appeared in the comments) is the question of whether the cat at the end is the cat - the one she earlier saw under the table.

I’ll discuss this below but first — in the comments, I posed a challenge question: does it matter whether this was the initial cat or a second one? Or, why would it matter?

To me it does matter, very much. Why? Well, it’s one story (and means in one way) if it’s the same cat, and quite another story (and means in a different way) if it’s a second (new) cat. Since the two meanings aren’t identical, it’s up to the writer to decide, and it’s up to us, his readers, to look closely for evidence of what he choose. That is, in my view, it’s not as good a story if we can’t discern which of these two possible versions the author intended. Moses sees the wild partying going on back at camp and throws the tablets containing the Ten Commandments down. Does it matter if they break? Since it does matter (it’s what sends him back up the mountain) the writer tells us this; it’s not as good a story if we don’t know whether they broke. It could still be a good story if they didn’t; but in any event, the version where the status of the commandments is specificed is better than the one where it isn’t (according to me).

The way I read the ending of “Cat in the Rain” (drum roll, please) is this: that’s an entirely new (tortoise shell) cat that the maid has scrounged up somewhere, ordered to do so by the padrone.

Why do I think this?

Well, first, we note that Hemingway did not specify the color of the first cat. And then he does specify the color of the second. It’s sort of like if I wrote, “Jim drove off in a car,” and then “Jim showed back up in a red car.” See how we assume those are two different cars? If I intended it to be the same car, I might have done something like, “Jim drove off in a red car,” and, later, “Jim jumped out of the same car he’d driven away in earlier” or “Jim jumped out of the same red car.”

Why didn’t Hemingway do it in a more straightforward way? That is, why is he forcing us to have this discussion?

He could have just said:

The American wife stood at the window looking out. Outside right under their window a small black cat was crouched under one of the dripping green tables. The cat was trying to make herself so compact that she would not be dripped on.

And then, at the end:

In the doorway stood the maid. She held a different cat - a big tortoise-shell - pressed tight against her and swung down against her body.

Why didn’t he? Well, he’s been using a very pared-back style throughout, as a matter of aesthetic principle. This laconic style is deliberate and is, we assume, part of his project. So, here, he is making a bit of a gamble, that we can infer that this is not the same cat - he is giving us just that much more credit as readers. Now, it’s a bit of a risk. I read this story many times before it hit me that it might be a different cat. And in the comments I can see that some of you either missed that or were not convinced But finally, while teaching the story, it hit me that it must be a different cat - for the reason mentioned above but also because (in my view) it’s a better story if this is a new cat. This reading provides one additional level of complication and, therefore, of meaning. She gets her wish - sort of, and not at all. And yet: her wish has been honored. (The padrone has understood, “I want that cat” as “I want any cat” and has…obliged.)

We might say that, with the “different cat” ending, Hemingway gets it both ways. We feel the satisfaction of “a” cat appearing at the end AND we get that little twist associated with it being a different cat - one that doesn’t fit her original bill (it’s not in need of rescue, doesn’t look like except, maybe, now, from the maid, and from the wife).

The story ends a bit like a joke, or an O. Henry story, doesn’t it? The feeling I get from it is a satisfying one…something like, “Well, whether we like her energy or we don’t, the world has responded to it.” Her position means that there are certain people (the padrone and the maid) who will try to fulfill her desires. It’s also a little dark; we might feel, “Yes, this is how power works in the world; thus it is. and always has been.” I wonder if she’s pleased by this gift of a random cat. Made angry? Shamed by it? Both, maybe? Some of you have noted that the cat at the end feels bigger than the earlier one and I agree. Bigger, more mature, somehow. (She did call the earlier one a “kitty,” after all, and this one does not seem kittyesque.) Also, where did this cat come from? It feels somewhat kidnapped.

There’s a feeling of “she got what she wanted,” along with “she did not.” There’s a feeling of “when we want something dearly, we sometimes get it, through our persistence, or at least a version of it,” along with “the privileged people of the world are always being served, by the servers.”

And, again: all of these feelings are present; none absolutely dominates. They flicker on and off. It’s something like looking into a hologram from different angles.

We also note that she is referred to here, at the very end, as “Signora.” I hear this as a sign of respect (the dictionary defines this as “a married Italian woman usually of rank or gentility,”) but also as sort of an automatic honorific - part of the maid’s obeisance.

But also, it’s pleasurable because I’ve been tracking these changing identifiers and Hemingway “knows” this and honors it. I feel seen by his inclusion of the word. And it means complexly, and this is the highest aspiration in fiction - to mean in a way that is real but eludes reduction.

As you might have noticed by reading the Comments - everyone brings what they have to this exercise. The exercise lures our issues (our approach, our obsessions, our obstructions) out into the sun. In my experience, that’s what any good writing or reading exercise does - it hastens the student’s progress in the direction she was already going and needed to go - gives her student something to react to and, in some private way, assimilate.

It might be good, now, to go back and look at that first paragraph again and see how Hemingway did. Is that paragraph from the wife’s point-of-view, do we think? Can we ask, again, how that paragraph “justifies” itself, now that we’ve read the whole story? And remember, these justifications can be very subtle, even too subtle to really articulate. Honestly, it’s enough just to feel those justifications - the way the story plays against the paragraph and vice versa.

I also feel inclined to paste in the whole text below, so you can read it all at once, finally.

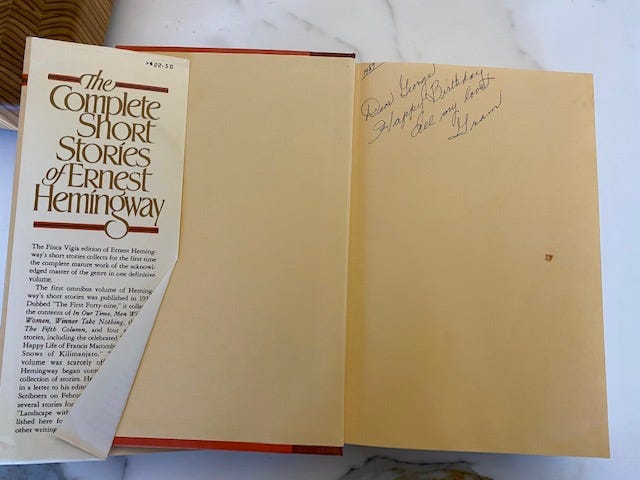

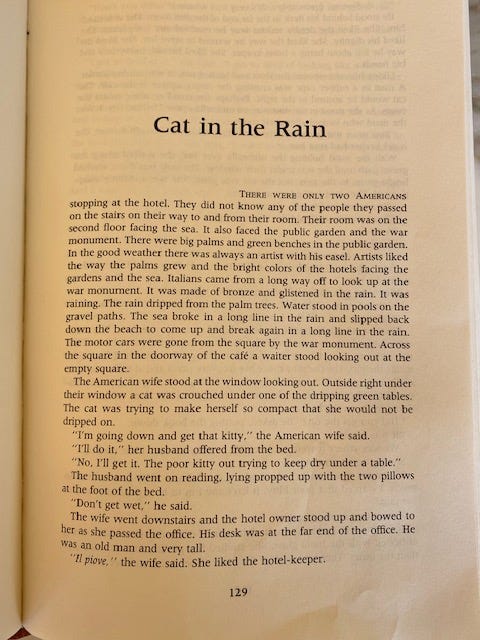

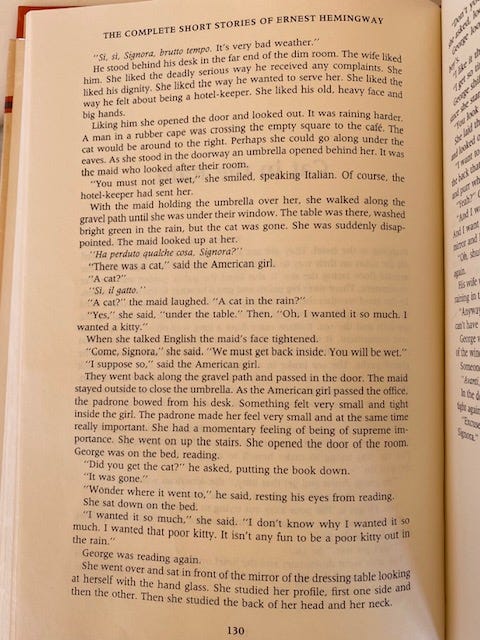

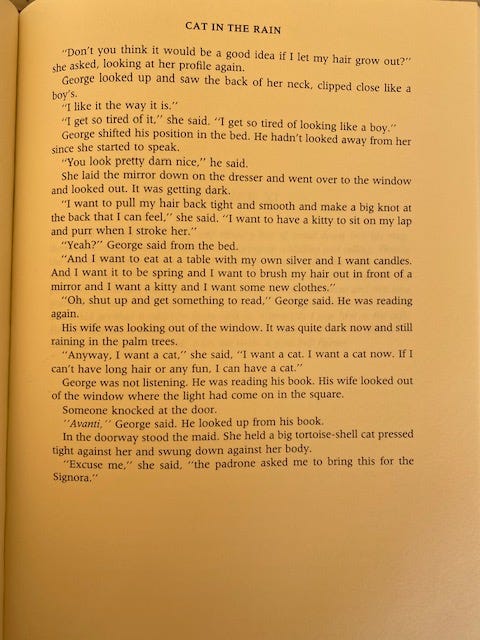

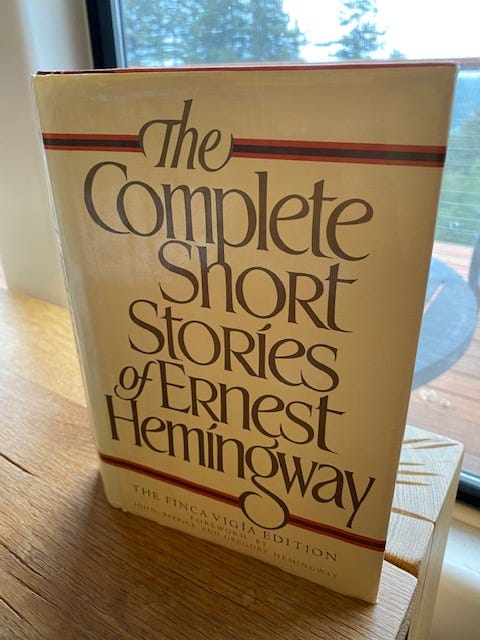

What follows is from “The Complete Stories of Ernest Hemingway: The Finca Vigia Edition,” Scribner’s, New York, ISBN 0-684-18668-3. (Apologies for the quality of the images here, and consider this a form of wabi-sabi and, if it pleases you, imagine me a few days before Christmas, running around our house, looking for the optimal counter to put the book on, so I could photograph it. Yes, Story Club is a very high-tech place.)

Why is that last page so much darker? Perhaps, I was being metaphorical, trying to subtly track the movement of the story (“It was quite dark now…”) or maybe…that one was taken on a different counter than the others. Who can say? Art is a mystery.

One subjective thing I’ll offer here. I very much admire this story but don’t love it the way I love, for example, certain stories by Chekhov. I think this is because of the way I feel Hemingway feels about these people. I think he looks askance at them somewhat, regards them with some distance and irony (even though I believe he and his wife were the rough models of these characters.) In Chekhov, I feel more fondness coming toward the author to his characters. Again, this is totally subjective, and I’ve heard from some people who read Russian that Chekhov, in Russian, reads more archly than he does in English translation. But when I’m doing that game called Ultimate Value, I put Chekhov higher than Hemingway and this is because, reading Chekhov, I feel more humor and tenderness which, then, gives me a sort of permission to feel those things, or try harder to feel them, for other, real, people. In this way, a writer can serve as a role model for us, a God-surrogate, asking and answering the question, “What is the highest way in which to regard our fellow human beings?”

Still, “Cat in the Rain” is, as that other George might say, pretty darn good, as evidenced by the passionate and wide-ranging discussion we’ve been having about it.

A word about this method of reading - I am not, by any means, suggesting that one would read like this all the time. It’s a sort of experiment, to get us looking at our reading minds. It works, I’ve found, in different ways for different people. (And not at all for others.) The actual experience of sitting down and reading this story in the 10-15 minutes it would take to read it at-speed is, of course, very different from what we’ve just done. In a sense, we’ve “sacrificed” the story, for this focused look at how we read.

On the other hand, I’d say that we do read this way, all the time - we ingest a bit of a story, a set of expectations and noticings occur, and we take these forward to the next bit. This is true whether we’re parsing it out or racing through it, I’d say. In this model, we’ve just taken a film of the reactions we would have had if we were reading normally, and slowed that film down. But, as some of you have pointed out, there can also be a sort of overthinking that accompanies this exercise - we’re given too much time to theorize between bursts of text, and are taken into places we normally wouldn’t get to (and thus the experience is fatally different from “real” reading.

I know that some of you are teachers. So, a quick word about how to do a version of this “Cat in the Rain” exercise in class.

First, photocopy the story. If you can find the Finca Vigia edition, just photocopy the three pages of the story (pages 129-131).

Then you’re going to hand the pages out, one at a time.

So: pass out page 129, have the students read it (err on the side of giving them too much time). Then open up the floor for discussion, asking where they find themselves, having read that page. The core question: “What did you notice?” Emphasize that even the smallest observation has value. The trick, in my experience, is to make them talk a little longer than is comfortable. Let there be some awkward silences, that will force them back into the text. It’s useful to keep a running log of their thoughts on the board. Any observation they make is valid; reject nothing.

Another question to keep coming back to: “What bowling pins are in the air?” (And underscore that even the smallest thing that caught their attention is, by definition, a bowling pin.)

Then pass out page 130 and repeat the above. Toward the end of the discussion, you might point out that there’s only half a page (34 lines) left, and ask them to imagine the ending (or even try to write it). What do they need to have happen, what questions do they want answered, for them to feel that this is a good, satisfying, story? Some have claimed that this story is a little masterpiece; is it, for them, so far (i.e., at the end of page 130?) If not, what is it going to take to convince them? It’s sometimes fun to have them talk through the different things that could happen - which are good things, which would seem cheesy? If Hemingway does X, how are they going to feel about it? And so on.

Then pass out page 131.

The magical thing about this exercise is that whatever the students say…is perfect. That is, it will work for your purpose. You just receive it, hear it, take it as a legitimate basis for discussion. You are…data-gathering, really; seeing what the story has caused in them. (Not how clever they can be about it.)

The real takeaway is: how much it causes to arise in them.

The goal is to get them out of “English class” mode (“Hemingway here is taking up the theme of…”) and into “true reader” mode – to get them talking frankly and honestly and unguardedly about their real, felt, reactions; about where the story has put them, about what questions it brought up for them; about any resonance the issues raised in the story has with their actual lives.

The most gratifying thing that can happen is this: you can make them see that their natural reactions to the story are valid and are, in fact, the only basis for criticism. It also, of course, forces them into a closer reading of the text.

Here’s the full text as we read it - this is off the internet so there may be some errors, relative to the Finca Vigia text, above:

Cat in the Rain

There were only two Americans stopping at the hotel. They did not know any of the people they passed on the stairs on their way to and from their room. Their room was on the second floor facing the sea. It also faced the public garden and the war monument. There were big palms and green benches in the public garden. In the good weather there was always an artist with his easel. Artists liked the way the palms grew and the bright colors of the hotels facing the gardens and the sea. Italians came from a long way off to look up at the war monument. It was made of bronze and glistened in the rain. It was raining. The rain dripped from the palm trees. Water stood in pools on the gravel paths. The sea broke in a long line in the rain and slipped back down the beach to come up and break again in a long line in the rain. The motor cars were gone from the square by the war monument. Across the square in the doorway of the cafe a waiter stood looking out at the empty square.

The American wife stood at the window looking out. Outside right under their window a cat was crouched under one of the dripping green tables. The cat was trying to make herself so compact that she would not be dripped on.

“I’m. going down and get that kitty,” the American wife said.

“I’ll do it,” her husband offered from the bed.

“No, I’ll get it. The poor kitty out trying to keep dry under a table.”

The husband went on reading, lying propped up with the two pillows at the foot of the bed.

“Don’t get wet,” he said.

The wife went downstairs and the hotel owner stood up and bowed to her as she passed the office. His desk was at the far end of the office. He was an old man and very tall.

“Il piove,” the wife said. She liked the hotel-keeper.

“Si, si, Signora, brutto tempo. It is very bad weather.”

He stood behind his desk in the far end of the dim room. The wife liked him. She liked the deadly serious way he received any complaints. She liked the way he wanted to serve her. She liked the way he felt about being a hotel-keeper. She liked his old, heavy face and big hands.

Liking him she opened the door and looked out. It was raining harder. A man in a rubber cape was crossing the empty square to the cafe. The cat would be around to the right. Perhaps she could go along under the eaves. As she stood in the doorway an umbrella opened behind her. It was the maid who looked after their room.

“You must not get wet,” she smiled, speaking Italian. Of course, the hotel-keeper had sent her.

With the maid holding the umbrella over her, she walked along the gravel path until she was under their window. The table was there, washed bright green in the rain, but the cat was gone. She was suddenly disappointed. The maid looked up at her.

“Ha perduto qualque cosa, Signora?”

“There was a cat,” said the American girl.

“A cat?”

“Si, il gatto.”

“A cat?” the maid laughed. “A cat in the rain?”

“Yes,” she said, “under the table.” Then, “Oh, I wanted it so much. I wanted a kitty.”

When she talked English the maid’s face tightened.

“Come, Signira,” she said. “We must get back inside. You will be wet.”

“I suppose so”, said the American girl.

They went back along the gravel path and passed in the door. The maid stayed outside to close the umbrella. As the American girl passed the office, the padrone bowed from his desk. Something felt very small and tight inside the girl. The padrone made her feel very small and at the same time really important. She had a momentary feeling of being of supreme importance. She went on up the stairs. She opened the door of the room. George was on the bed, reading.

“Did you get the cat?” he asked, putting the book down.

“It was gone.”

“Wonder where it went to,” he said, resting his eyes from reading.

She sat down on the bed.

“I wanted it so much,” she said. “I don’t know why I wanted it so much. I wanted that poor kitty. It isn’t any fun to be a poor kitty out in the rain.”

George was reading again.

She went over and sat in front of the mirror of the dressing table looking at herself with the hand glass. She studied her profile, first one side and then the other. Then she studied the back of her head and her neck.

“Don’t you think it would be a good idea if I let my hair grow out?” she asked, looking at her profile again.

George looked up and saw the back of her neck, clipped close like a boy’s.

“I like it the way it is.”

“I get so tired of it,” she said. “I get so tired of looking like a boy.”

George shifted his position in the bed. He hadn’t looked away from her since she started to speak.

“You look pretty darn nice,” he said.

She laid the mirror down on the dresser and went over to the window and looked out. It was getting dark.

“I want to pull my hair back tight and smooth and make a big knot at the back that I can feel,” she said. “I want to have a kitty to sit on my lap and purr when I stroke her.”

“Yeah?” George said from the bed.

“And I want to eat at a table with my own silver and I want candles. And I want it to be spring and I want to brush my hair out in front of a mirror and I want a kitty and I want some new clothes.”

“Oh, shut up and get something to read.,” George said. He was reading again.

His wife was looking out of the window. It was quite dark now and still raining in the palm trees.

“Anyway, I want a cat,” she said, “I want a cat. I want a cat now. If I can’t have long hair or any fun, I can have a cat.”

George was not listening. He was reading his book. His wife looked out of the window where the light had come on in the square.

Someone knocked at the door.

“Avanti,” George said. He looked up from his book.

In the doorway stood the maid. She held a big tortoise-shell cat pressed tight against her and swung down against her body.

“Excuse me,” she said, “the padrone asked me to bring this for the Signora.”

All right - well done. I never would have imagined the energy and depth of your engagement with this story (and your patience) and to say I am pleased and impressed would be a huge understatement. Bravo to you all.

I’ll be back on January 6, with a little essay that will NOT be, at all, about “Cat in the Rain.”

Happy New Year.

And the big question: what made us keep going, line to line? What are the micro-qualities of the prose (word choice, rhythm) that compelled and intrigued us? The pattern of knowing, then wondering, etc. Or, more broadly: Can you draw any conclusions on how YOU read? What are you looking for, line to line? And so on.

One thing the first paragraph does for me is remind me what a great big world is out there, a world with wars and heroes and art and artists and the vast oceans. The American wife’s desire, her longing, wouldn’t feel as real without that paragraph.