So, thank you all so much for your enthusiastic participation in the exercise. There were some truly lovely stories posted. I applaud your collective talent and bravado.

If you’ve done the exercise, in a sense, you don’t need for me to tell you what it did for (or to) you. You know. Whatever slight alteration occurred in your feeling about your process…that’s the lesson.

But…

In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain,” this exercise was presented in Appendix B, as “An Escalation Exercise.” I just now made several attempts to paraphrase the discussion that accompanies the exercise and, in the process, got reconverted to the old “writing is rewriting” mantra; the version in the book, extensively rewritten over many months, turned out to be (surprise!) tighter and less gabby than what I was able to come up with in one afternoon.

So, I hope you won’t mind if I reproduce it verbatim below (and then follow it with a few new thoughts).

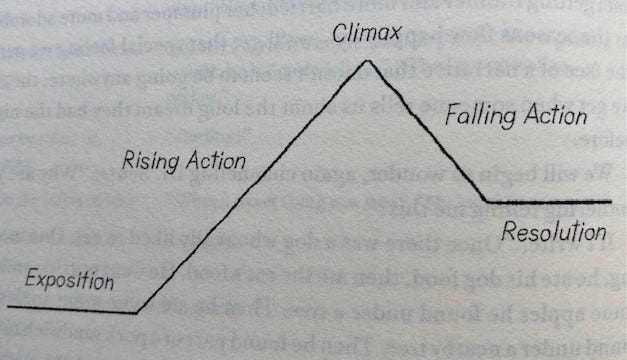

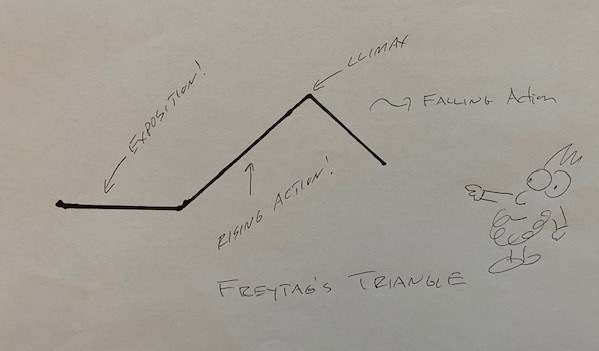

Most writers tend to write stories that are long on exposition but never ascend into the rising action (that is, they don’t escalate). I’ve read entire student novels like this—pages and pages of brilliant exposition in which the tension never rises. I sometimes say that in the exposition we put a pot of water on the stove; getting the action to rise is making the water boil. (What we’ve been calling “meaningful action” is equal to the boiling water is equal to escalation.)

For reasons I don’t understand, the stories produced using this exercise almost always have rising action. For certain students, they tend to be funnier and more entertaining and more dramatically shaped than those writers’ “real” work.

If you like the piece you wrote—if it seems to have something your more seriously produced stories lack—you might pause here and ask what that is, exactly.

Why does this exercise work? I’m not sure. The constraints have something to do with it (the 50-word limit and the exacting—200, not 199, not 201—word count). When a person is doing this exercise, her attention is on those constraints, which means she’s approaching things differently than she normally would. The part of her mind that would usually be thinking about her themes or preserving her style or the piece’s goal or her politics is being kept busy counting words. Which allows another part of her mind to step forward, a less conscious, more playful part.

When I assign this exercise in class, I announce beforehand that everyone will be reading their story aloud afterward. This intensifies things. (“Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”) This brings out a natural performative streak that just about every writer I know has.

When I was a student at Syracuse, our teacher, Douglas Unger (author of Leaving the Land, among other books), a little fed-up, I think, with how clever and “literary” the stories we’d been writing were, announced, just before a break in workshop, that during the second half we were each going to have to tell a story on the spot.

Talk about a nerve-filled break.

But compared to the stories we’d been submitting, the stories we told that night were, without exception, livelier and more dramatic and more infused with who we really were, richer with our real charms, the way we actually were witty in the world.

What is there to do with the little pieces that result from this exercise? They usually sound a little strange, Seussian. Once a student made a larger story out of several passes at this exercise; in each pass he used a different fifty-word set, but he kept the same characters throughout the longer story he made of those 200-word bits. Other students have used this exercise to generate a sort of starter piece, with good rising action, then relaxed the constraints and rewrote the story using as many “new” words as they wanted.

The beauty of this exercise is that it shows us that we usually walk around with a certain idea of the writer we are in our head. When we sit down to write, that writer is the one we start channeling. In that instant, our brain function changes. We’re less open to what the story wants to do, to what that language generator inside of us wants to do. We’re working within the narrow range of how we think we should write. This exercise shuts down that way of thinking by keeping it busy with the practicalities of the exercise, which leaves the rest of the mind asking, “Well, what else have we got?” That is: “What other writers might be in here?”

Maybe this exercise is a bit like dancing while drunk and filming it. In playback, we might catch a glimpse of something we don’t normally attempt, but that we like. And if we like it, we might want to do it on purpose, later.

Right, well said, George from last year. I approve that message.

A few additional things we might think about together:

What does your mind look like in the instant before you start writing? What’s in that little thought-cloud over your head? There might be a sort of default voice in there - the one you usually revert to. There might be some assumptions about how you are going to proceed; some aspirations; some self-remonstration. There might be the killing weight of the entire Western literary canon, saying, “Don’t mess up.” There’s no right or wrong answer. But the state of our mind as we start is going to determine what comes after, so…

Now: how was that state-of-mind different, as you approached the exercise? Some of my students have reported feeling less stressed at the beginning of the piece - because it was a classroom assignment, because it was goofy, because it was timed, and so on. It was assumed that this was not their “real” work and that nothing much was expected to come of it. They could just relax, have fun, play a little.

For my money, that’s a pretty good mindset to be in when starting anything. I’ll sometimes say to myself: “This isn’t THE REAL ONE. It’s just a practice run for the real (great, classic, epic) story I’ll write…someday. This story is just something to keep me busy while I wait for that future time, when I’ll be amazing. Working on this (minor, inconsequential) thing might teach me something I’ll need to know (for my masterpiece).

Another form of this mantra, one that is very important to me: “This story doesn’t have to do everything; it just has to do something.”

And meanwhile, there’s a quieter, background, mantra: “The worth of this piece is ultimately going to depend on how hard I work on it.”

So, in a sense, I’m having it both ways: to ease my way in, I’m conceding that this is going to be a minor story, just for fun, no big deal, likely a piece of crap, while also saying, “Hey, you never know.”

This was the mindset in which I started "Lincoln in the Bardo.” I said to myself, “This probably won’t work, but I hereby grant you, George, a six-month trial period. Go ahead and waste those six months. No pressure. It’s just for fun.”

Another thing to think about: what was in this piece that isn’t in your “real” work? It might be beneficial to think a little about how it felt when you were writing your piece. What were you “following” as you wrote? What was leading you onward? On what basis were you making your decisions? Was this different from your usual method?

This is, of course, an exercise about constraint.

But then again, we self-constrain in every piece of writing. When we write a first paragraph in a certain voice, we are making a constraint for ourselves (“Whatever you write next, keep it in connection with what you’ve already written.”)

If I blurt out a sentence like, “Honestly, Steve, your frustration-expression tendency is really starting to ratchet my Flintlock Meter.” Well…that’s a constraint. The reader is going to read whatever follows as being in connection with that first sentence…and so we are under constraint.

Art might be thought of as the act of performing admirably under constraint. And, conversely – it’s not possible to make a beautiful work of art in the total absence of constraint – with “constraint” being understood as “everything that has preceded the current moment in the story.”

Another thing we might think about is the way that one thing that helps shape a piece of short fiction is the reader's knowledge of...its brevity. That white space at the end rushing up. And here. as I was reading your exercises, my internalized knowledge that it was only going to be 200 words. That creates a nice sort of pressure - like someone saying goodbye to a lover as the train pulls away. But this is true even for a novel - we know it is going to end, and is, therefore, shaped.

Also: the idea that "rising action" might have something to do with "returning to those things we have already set in motion" - and here, that's enforced by the constraint. So if we use the word "river" and are forced to come back to it - that feels like a focusing of effect, maybe?