Hi all,

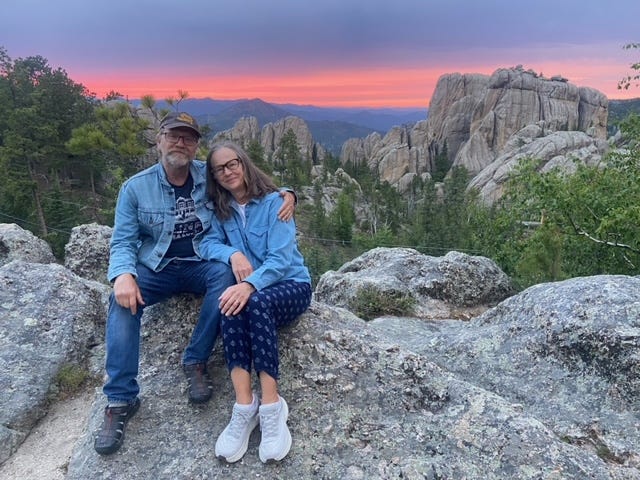

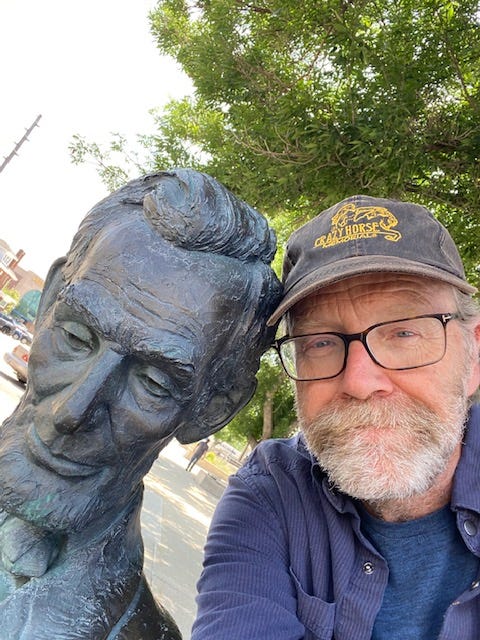

Back from a wonderful vacation in South Dakota, getting ready to get back to work, feeling, of course, agitated and anxious about our national politics, but also freshly in love with the amazing natural beauty of our country, and happy to launch into this week’s question.

Q.

Hi George,

I have a question about how you think about a work in progress when you’re away from your desk. From what you’ve shared, I know that much of your creative decisions are based on an incredibly close, sentence-level engagement with the piece. Because this is divorced from considering larger themes, plot points, etc., do you try to keep yourself from thinking about a story too much (to avoid needlessly planning ahead) when you can’t actually work on it? Or do you allow yourself to sit with characters and develop them further, entertain different plot points or debate where a scene might fit as you go about your day?

Because I also feel that so much depends on the nuance of a particular line and where it may lead, I usually try to stop myself from contemplating a work while I’m away from it. I try more to retain the nonverbal inspiration (mood, image) that started me on the piece, but am afraid of going further. However, I sometimes wonder if I’m needlessly hampering myself and should instead try puzzling through more of the story when I’m not at my desk, if for no other reason than to gin up my desire to head back to it.

Since you’re a full-time writer, this question is probably less relevant than it was when you first started writing (and could devote much less time to it.) And if the answer is merely “I don’t”, I would completely understand.

Thank you for considering!

A.

What a smart, interesting question. My “purist” answer is that I try not to think about a story at all when I’m not actively working on it - that is, sitting there re-reading it. I just switch off at the end of the writing day, confident that my subconscious is going to keep working on the story, and that it’s going to do a better job of that if I don’t bother it with a lot of thinking.

Is this entirely true? No way.

Let me explain.

There’s a certain feeling I get when I start thinking about a story while not working on it. Depending on the flavor of that feeling, I’ll go ahead and entertain that thought, or not.

I’ve learned to recognize (mostly) the difference between two modes of thinking: passive thinking (good) and aggressive thinking (less good). In “passive” thought, the thought comes to me; in “aggressive” thought, I go after the thought.

(I just made up those terms, by the way.)

But (let’s say), “aggressive” thinking has a seeking/“I need to figure this crap out or I’ll go crazy” feeling, whereas “passive” thinking is more like throwing out a line and seeing if anything bites. In this mode, a solution will just sort of…appear. (I might not even be thinking directly about the story when that solution presents itself.)

Or, I’ll be thinking about the events of the story in a more holistic, “what if this happened in real life” way. And then an idea comes (I feel like saying it “arises”) and the effect is less like solving a puzzle and more like when one overhears someone says something true, the truth of which one has maybe never recognized before. (More of a “Oh, sure, that makes sense” feeling, and less of an “Aha!” feeling, maybe.)

When working on a longer piece (Lincoln in the Bardo and some of the longer stories) I sometimes find myself loosely telling myself the story, to get more clarity on what the big motions of the story might want to be. “So, O.K.: Lincoln leaves the crypt after that first visit. Where does he think he’s going?” Or (re “Liberation Day”): “I wonder if there’s any other good chunk of the Custer story I could use, which would therefore let me prolong the foreground story?”

I just pose the question and listen for an answer that has some energy (as opposed to asking the question and “working at” answering it, if that makes sense). I’m turning my mind lightly in that direction, trying to stay loose about it, waiting for a natural, conversation-type answer to come lightly back on its own: “Well, George, seems like, based on what Lincoln just said a few pages ago, he’s on his way out of the graveyard, at least for tonight.”

And then, maybe, I reply, “Ah, I see. So, since we don’t want him to leave yet, I guess we’ll have to come up with some believable, holistic event to keep him here.” To which I might reply: “True. Good one! Agreed. Now that we’ve formulated that question, how about we don’t try to answer it just yet, but, instead, let it hang around in our mind awhile. We’ve formulated the dilemma correctly, at least.” And then, being the agreeable guy I am, I go ahead and agree with myself: “Sure. Let’s go for a walk or keep doing the dishes, while thinking about something other than the book, and we’ll see what happens in the writing room tomorrow. We’ve planted a good seed with this thought.”

My favorite example of this sort of self-interrogation happened with the story “Sea Oak,” as I think I’ve detailed here before. I’d killed off this character named Aunt Bernie and, in the shower, I said to myself something like, “She was the most lively person in the story. Why’d you kill her off? You know she’s going to have to come back., right?” And, this little voice in my head spontaneously completed that sentence, like so: “Yeah: back from the dead.”

It was a linguistic thing – my mind automatically completing that sentence with the familiar phrase “back from the dead” – that then became a plot thing, which then became a theme thing: this working-class woman was going to be (next morning, when I started working again) someone so embittered by the way she was shortchanged in life, that her rage would compel her right out of the grave.

But I should say/admit – with that story, before that moment, there’d also been a lot of (years of, actually) more “aggressive” thinking: outlines and graphs and even some clumsy “logical” efforts to get Aunt Bernie back into the story by way of flashbacks and memories and dream sequences and so on. So, the assertion that she was going to “have to come back” was already in place, and I’d already tried a whole bunch of obvious, rational ways to “get her back” into the story.

And then there was that strange, mysterious voice, solving the problem for me, and not entirely unsummoned - I was thinking about the story, and with some angst. But, in that moment, I was definitely not in “figure it out” mode. I was more in “self-accusatory” mode (“Why can’t you finish this story, idiot, after six years? Are you a professional or not?”).

So, it might be the case that the “aggressive” thinking is not “bad” or “wrong” at all, but exists to enable the “passive” thinking that might eventually lead to a solution. We might even say that NO approach or habit is wrong - they are all just parts of our peaceful little creative army, that step forward, trying to be useful, and sometimes they are useful, and sometimes they’re not, and our role, as the peaceful general of that army, is simply to say: “Not so much of that, please,” or “That approach doesn’t seem to be working this time,” or “I’ve always claimed this approach is bad, and yet, since it’s working, I’ll just stay quiet.”

What that general doesn’t say is, “I have arrived at an answer for all time, and I need never consider this question again.”

You say something very wise here, dear questioner: “so much depends on the nuance of a particular line and where it may lead.” This is exactly right, in my view. An idea, in the abstract, is one thing; an idea put up on its feet, in the context of that particular moment in a particular story, is quite another. Things can seem inspired in theory and not work at all in practice.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve come up with some perfect idea while wandering around the neighborhood, then come home, dropped it into the story – and found it to be completely off.

It was right, in theory, but wrong in practice. And the way I knew this was by reading the whole story up to that point and being honest about my reaction in that moment. For me, that’s the litmus test.

Imagine if someone set us this challenge: Come up with just the right thing to say at the party you’re going to be attending tomorrow night.

Some natural questions might be: At which point in the party? To whom? In reference to what?

Imagine if, without answers to these, you just made something up and lurched into the party and blurted out that thing.

What are the odds that it would be just right?

Of course, in StoryWorld, it’s a little different: you know which party you’re attending and you, sort of, know the moment. But, my view is, you have to be experiencing that party in real-time (i.e., re-reading your story with as fresh a mind as possible) to know what precise moment you’re actually in and, therefore, exactly what to say. And, once you’ve written it, you have to read it again, to know if what you’ve just said was right or not.

Complicating matters, that answer may flicker back and forth between “right” and “wrong” over various subsequent re-reads.

But: that’s wit, really: being fully in the moment you’re in and then responding accordingly, with as little conceptual overlay as possible - just trying to be right there where your reader will be.

You’re there in her mindset and you set a generous little Wit Trap, which she then tumbles into, delighted.

Here’s a mistake I sometimes make: I just “want” to write about a particular thing, and then, therefore, just…cram it in there. Regardless of what the story wants.

That is, I’ve done some away-from-the-story thinking of the “aggressive” variety – my mind, excited by the story, starts roaming around, in search of ways to expand it, or to incorporate some bit of research of which I’m proud. Or I’ll overhear someone saying something and decide that must be incorporated. Or I’ll decide that the story’s rhetoric needs for me to take into account X or Y (just because I’ve encountered X or Y in the real world). Or, I’ll suddenly see my story as a vehicle for some philosophical or political viewpoint and start mentally developing ways for the story to serve that viewpoint.

Meanwhile, the story’s sitting over there, interested in expanding only organically, in ways it feels are necessary. And when I bring it this new “gift”….it’s not thrilled.

And, like a body into which the wrong organ’s been transplanted, it rejects that “gift.”

For me, most of this happens by feeling – I know, or think I know, what a genuinely good idea feels like as it arrives, and I know what it feels like when, fueled by desperation (“Come on! You’ve been working on this story for over a year, dummy!”) I try to enforce my will on the story.

Finally, just a reminder: all such advice or musing exists profitably only as an example of how one person (me) does it. It’s just my way and, as I re-read the above just now, it struck me how partial and incomplete and wooden even this account is (how unlike the way I actually work) although I’ve tried my best to be as honest as possible.

So, as always, please consider any advice from me as just an invitation to think about how YOU do it. Any way is fine, if it works for you. (I know there are writers who do a LOT of thinking and planning off the page, from which their work benefits.)

What we’re doing here – and you’ve done it perfectly, dear questioner – is turning over certain stones as a means to encourage ourselves to consider our own approach, so as to, maybe, expand/develop/enliven that approach.

How about you, Story Club? What sort of off-the-page thinking do you do?

I agree with George that “it might be the case that the ‘aggressive’ thinking is not ‘bad’ or ‘wrong’ at all, but exists to enable the ‘passive’ thinking that might eventually lead to a solution.” In fact, I think I’d go so far as to say aggressive, conscious thinking could well be necessary to push the problem into the unconscious mind. In one of his essays, Oliver Sacks recounts an experience the French mathematician Henri Poincaré had in 1880. For fifteen days Poincaré worked intensively on a complex mathematical problem, then his labors were interrupted by a lengthy trip, during which he forgot all about the problem—at least consciously. One day late in his trip, he stepped onto an omnibus and the solution to the problem popped into his head. This “sudden realization,” Poincaré wrote, was “a manifest sign of long, unconscious prior work.” This and other similar incidents in Poincaré’s life convinced the great mathematician that, as Sacks says,"There must be active and intense unconscious activity even during the period when a problem is lost to conscious thought, and the mind is empty or distracted with other things. This is not the dynamic or 'Freudian' unconscious, boiling with repressed fears and desires, nor the 'cognitive' unconscious, which enables one to drive a car or to utter a grammatical sentence with no conscious idea of how one does it. It is instead the incubation of hugely complex problems performed by an entire hidden, creative self." And this hidden, creative self is our wiser self. As Poincaré said, “The subliminal self . . . knows better how to divine than the conscious self, since it succeeds where that has failed. In a word, is not the subliminal self superior to the conscious self?” I agree. And I think the experience Poincaré describes is not unusual but actually something we all commonly experience. For example, we might spend an hour trying to remember the name of a song or a book or whatever, and come up empty, but then some time later, while we’re just walking down the street or opening a refrigerator and not consciously thinking about the problem anymore, the answer pops into our head. I think Einstein sums up creative process well: “I think 99 times and find nothing. I stop thinking, swim in silence, and the truth comes to me.”

The timing of this post is interesting. It popped up on my screen shortly after I had made the decision to stop writing and go to the pool. I was debating whether I should bring my notebook with me and my map of scenes. I decided to pack a copy of The New Yorker instead to give my brain a little break from thinking. But I suspect that it will carry on thinking about the story even when I read The New Yorker, in that subconscious, passive way. I actually get my best writing ideas when I give my brain a break and read for pleasure, or even do something as simple as take a pee break. Like Mary, my aggressive thoughts tend to be unhelpful. They are the bully that attempts to block the creative process. Usually out of fear, which is understandable. But in my creative practice solutions come from a state of flow and letting go, rather than desperate control. The challenge is - how do I get myself there? I remind myself that no one will die from my bad writing, I take long walks, exercise, practice yoga and meditation and make sure to fill my well. I continue to admire the honesty with which you write about your writing process! It’s very inspiring. And this community has always so many interesting things to say. Love it here