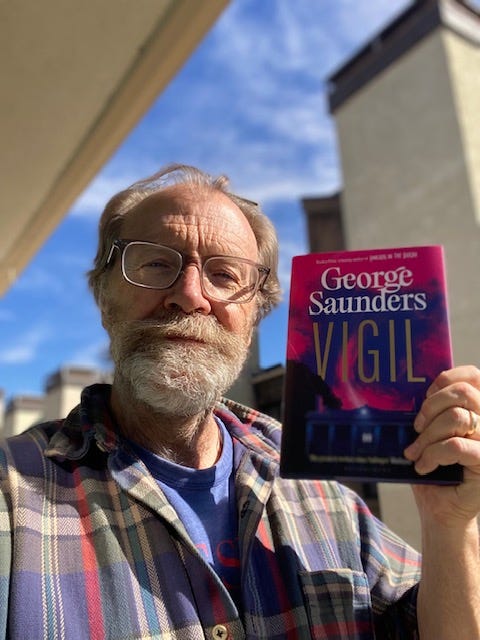

I just got my first look at the finished U.K. edition of Vigil and it looks gorgeous:

You can pre-order a signed copy from my friends at Waterstones here.

Really looking forward to coming over to the U.K. in February and to my conversation with Richard Ayoade in London (on 2/17) and with Heather Parry in Edinburgh (on 2/19). Tickets (not many, however) are still available for these two events. My event with Max Porter (on 2/18 in Bristol) is, both sadly and happily, sold out, but you can get on a waiting list here.

Also, this lovely profile by Sophie McBain just appeared in The Guardian. This was the first interview I did for Vigil, back a few months ago, and Sophie and I had a wonderful, free-wheeling, two-hour conversation at the Warwick Hotel in New York, which Sophie did a virtuosic job of condensing in the piece - she really caught the tone and feeling of that very energizing visit. Thank you, Sophie.

I also wanted to let you know the happy news that our beloved dog Guin is feeling better. We were really worried earlier this week but then found out she has a urinary tract infection, and she’s already done a beautiful bounce-back on the meds.

I’m getting a real life lesson about not presuming that what appears to be going on actually is, and about persistence through difficulty - kind of like, “Don’t get too emotional; just keep doing the thing that might help.”

Thank you all, so much, for your expressions of support and the stories of your own dear pets…it really helped.

And thank you to the great Paul Karasik (Story Club member, New Yorker cartoonist, and host of this always lovely and inspiring blog, for this drawing of Guin he sent me when I was at my lowest moment:

And here’s Guin herself, last night, already feeling better (and she’s feeling even better this morning):

Thanks to The New York Times interview (video and podcast links below), we got a huge influx of new subscribers. Welcome to all of you. If you are (or should soon choose to become) a paid subscriber, you’ll have access to a vast trove of posts (and the associated comments) dating back to the early Story Club days. (Becoming a paid subscriber also lets you post comments….which is a big part of the fun here, where we have one of the most erudite, generous, and good-hearted communities….well, anywhere.)

I thought it might be fun to ask our long-time members if they have a favorite story or Office Hours from the past.

If you do, please tell us about it here, in the Comments:

Our usual convention is to discuss a published/classic short story on Sundays. There’ll be a little departure next Sunday, when we’re discussing an exercise I gave two weeks ago.

On Thursdays, we do something called Office Hours, where I answer questions submitted by paid subscribers (yet another reason to leap, with grace and verve, over the paywall).

So here’s this week’s question, which was identified, in the email subject line, as “A Question about “A Question about The Question,” referring to this earlier post.

Q.

Dear George,

Apologies for the overly-meta subject line — the idea of a post titled that just made me laugh. I’m writing with a question about the post I’ve name-checked, specifically this passage (feel free to cut/condense the quotation passage if need be):

“But sometimes the touchstone can inhibit – it suppresses the subconscious. We get the benefit of feeling that we’re in control (by way of our method or mantra) but the story doesn’t like this, and may go off and pout in the corner while we (logically, in-control) flail away at it, frustrated, in the end, by how quotidian and predictable it has become…”

So, the question this passage sparked for me: what is a writer to do if they have the opposite problem, meaning that they do not desire to be in control and need to let go, but rather cannot escape the reality of any fiction’s malleability, and wish they could somehow forget they are in control?

Perhaps it has something to do with my being autistic, but much like the metaphors some writers use likening their process to gardening, I have never found this sort of personification of a story relatable. Perhaps it accurately captures how writing fiction feels for many writers, but personally I have never been able to trick myself into forgetting the empirical reality that what the narratologists call the diegesis, the fictional world, is not real, and therefore is eternally mutable at the hands of its creator. The brute fact is that a story is not a living organism, has no will, and is absolutely in a writer’s hands — she can do whatever she likes with it and there is literally nothing that could stop her. Perhaps there are certain choices she is unlikely to make, because they would result in the kind of end product that her culture has taught her to view as hack, cliched, boring, absurd, random, contradictory, nonsensical, etc., but still, she could make them.

I suppose I worry about this as there is a narrative, hanging in the air and suffused through literary culture, that following the subconscious or the intuition is the only true path to creating thematically rich fiction that is nonetheless not “preachy” or “overdetermined.” So, if a writer can’t banish the conscious mind in favor of the unconscious, are they doomed to writing “quotidian and predictable” stories? I’ve never been able to meditate either, and not for lack of trying!

A.

Thank you for the interesting question.

What I’m talking about above is simply the experience we’ve all had, of over controlling a narrative to the point where it’s more a screed or lecture – a static demonstration of some idea we hold (it can be a political idea, or just an idea about what the story is "meant” to do).

This tends to be, when I do it, boring and one-sided: me droning on to my poor reader, correcting or instructing here.

Whereas I think a work of art can be more of a two-person (reader and writer) exploration of an idea. A dance, a call-and-response game.

But I couldn’t agree more: the fictional world is not real and it is indeed infinitely malleable - that is entirely, sometimes maddeningly, true. (As some of you who are doing the Sunday exercise may be finding out, a text can be changed an infinite number of times.)

But that’s the fun of it, really: we are making an object. The relation of that object to the real world is…up to us. That object is distorted and exaggerated — it has our stamp on it. It should, it has to, be interesting. And that stamping requires deciding, over and over again — by taste, whimsy, intuition — or by any other means that feels vital to you.

So the question is: what sort of object do you want to make?

And the next question is: how do you go about making that object? (How do you get your object closer to something that delights you and makes you proud, even giddy, to have done it?)

The process I’m fond of involves putting aside larger conceptual ideas, as well as my planning impulse, and to focus on improving (per my personal taste) the quality and speed and general zing of the prose – not only in the lines but in the overall movement and structure of the thing.

But the larger conceptual ideas are still going to be there, trying to crowd up to the table, and one can’t help but be aware of them. Each writer has to decide for himself how much he’s going to tolerate, and indulge in, those ideas.

So, yes: the prose could, indeed, go on changing forever, but the question is, which version do you like best? And that’s up to you.

If you imagine generating, say, 10 versions of the same swath of text (as those of us who are involved in that Sunday experiment may have done by now) which do you prefer? That is, if suddenly your book was to leap into print and be on bookshelves all over the world, which of those many versions of that paragraph would you want in that book? Which would you stand by?

So, I don’t think you have to worry about surrendering to the subconscious or any of that. Just proceed through your text, seeing if it pleases you, and make changes accordingly.

You are just preferring, over and over again, in whatever way you naturally prefer.

Finally, importantly, let me restate a recurring Story Club caution: when I suggest something in a post, it’s never the only way, or the best way, or the respectable way — it’s just one of many possible ways: a suggestion.

Imagine, if you would, that you’re the “teacher,” looking down on a doorless room in which the “student” is trapped. You’re shouting down, “What’s behind that painting?” or “Is there a loose floorboard?” In other words, you’re trying to help. A lot of what you say might not help at all. It might even hurt. It might confuse the student or, as seems may be the case with you dear Questioner, it may distract you into a mode where you are trying to square my conception of the thing with yours.

And the person offering the advice is not claiming, at all, that those suggestions are going to work. (If the “student” moves the painting and there’s just wall there, that’s fine — he doesn’t have to keep “moving the painting.”)

So, if you feel that you “have never found this sort of personification of a story relatable,” I would say: God bless, and good self-observation — please just abandon that idea altogether. If it’s not helping, walk away. Go forth and find your way of thinking about it, and thanks for trying my suggestion.

But anytime thinking about writing gets us tied up in knots and frustrated, we should remember that it’s all just concepts — the “finger pointing at the moon,” as we Buddhists say. The explaining how one does is not the doing of it.

My true advice is: if something you read about craft, here or elsewhere, frustrates or impedes you, just say: “Thanks, but no thanks,” and move on.

Truly.

P.S. Here again are the links to the Times interview(s)…

Written interview.

Video interview:

Podcast:

“I thought it might be fun to ask our long-time members if they have a favorite story or Office Hours from the past.”

One of my favs was Tillie Olsen’s “I Stand Here Ironing” from May, 2022, and it was extra fascinating when Julie Olsen Edwards, Tillie Olsen’s daughter, chimed in with even more context. I love that! Such a surprise! Here’s the links to the story and the Story Club from waaaayyyy back when.

https://shortstoryproject.com/stories/i-stand-here-ironing/

https://georgesaunders.substack.com/p/i-stand-here-ironing-2

Maybe it's recency bias, but of all the wonderful stories we've discussed here, the one that stands out for me is Samanta Schweblin's story, A Fabulous Animal. The entire story felt like a masterwork - every word and sentence so carefully crafted and placed, and doing so much work. That scene at the end has haunted my mind (in a wonderful way) ever since. The discussion in this group was, as always, really illuminating. Also, just this week, someone in my writing group handed in a story that left me, at the end, thinking, WHAT just happened?? And, as with A Fabulous Animal, I was able to love the story deeply without needing to understand it all. (also ... glad to hear the good news about Guin!)