Office Hours

Writing for kids, "The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip" - and a special guest

Q.

I’m curious if you’d be willing to discuss the process of making of “The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip.”

I would love to hear your thoughts on writing for a younger audience— is that even something you thought about when making the book? Was there anything different about how you approached that particular story? I’m also curious, given your musings on endings, if you thought much about how it would/should end, given the younger age of the audience. (Did you even know who the audience would be when you began?) If so, did you feel the need to create a sense of resolution and hope that you might not have been inclined toward if it was a story (like “Sticks”) for adults?

“Gappers” has your characteristic humor in the presence of darkness, your tendency toward a clear-eyed truthfulness about the human condition (exploring human selfishness, vanity, greed, moral superiority etc.) but also a tenderness and playfulness that I love.

I’d love to hear anything you’re willing to share about that process.

A.

Well, first, thanks so much for this question, which gave me a chance to remember that book from so long ago (the ancient year of 2000 (!).

The book came out of the experience of reading to our daughters, who were very young then. Usually we’d read to them at bedtime, and I always enjoyed that – doing the voices and so on – but then, at some point, they asked me to just tell them a story, to make it up on the spot.

So, I tried.

If you’ve ever tried this yourself, you’ll know that two beloved kids is a great audience. If they’re bored, they fall right asleep. If something you make up is unlikely, they let you know. But, on the other hand, if you get something right, you can feel it – the excitement, the impatience, the laughter, all of that.

For a writer like me, trying to improvise a story on the spot was daunting. (What? No revision?). So, the first few times it felt like an oddly high-pressure situation, (although our daughters made it less so, by how accepting they were of whatever I happened to come up with). But I do remember that dreaded feeling of having painted myself into a corner that I couldn’t get out of, not on that short of notice.

Sometimes I’d just end by going, “Well….not a great one tonight.” And they’d let me off easy with me a few gentle words (“No, Dad, it was good. Really. It was fine. I liked the part where…”) because that’s the kind of people they were, and still are.

Before long these stories all started being about the same young, female character, and they took on a certain shape. She was usually smart and somewhat reserved, looking out for the people around her, who were generally neither smart nor reserved.

On a few occasions, if I liked what I’d come up with, I’d go up afterward to the attic, where our one family computer was, and jot down a quick outline of the story.

Most of these, when I’d come back to them later, seemed kind of random and unshaped. But one of them, that concerned a girl who lived in a town being overrun by these little monsters from the sea, had a shape that I liked, as well as the makings of a few funny set pieces.

So, at some point, I decided try to write that one up - to polish and finish it.

And after a few years of trying, this became “The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip.”

Your question about the ending is sort of contained, or foreshadowed, in the origin story above. When I would tell those stories to our girls, the goal was consolation. Well, actually, the goal was fun, but fun that had, in the end, a consolatory shape: the problem posed in the story got solved, all was forgiven, everyone in the world of the story did what we were about to do, which was end a day, one of the many precious days we’d been given, in a happy, hopeful, grateful state of mind.

In other words, what I was doing as I was telling those stories, was trying to make a positive experience for our kids.

In those days, that old line about what art should strive to do was very alive for me: “comfort the afflicted and afflict the the comfortable.” This would have been around the time I was writing adult stories like “Sea Oak” and “Winky” that were definitely about afflicting the comfortable; pointing out that, just because things were good with you (with me) they weren’t necessarily good everywhere.

That was at least part of their intention.

But what I wanted to convey to our kids on those nights was that, although sometimes people are, yes, crappy and the world can be rough, we do have resources with which to fight back. And while fighting back, we still have a responsibility to retain our self-control and, even, maybe, some compassion for our enemies.

Part of the function of the adult stories I was writing back then was to challenge what I felt at the time to be an auto-optimistic assumption about endings (“The writer must give hope!”), that tended (I felt) to overlook people who were struggling; to remind the reader (and myself) that the world sometimes isn’t fair (and that power is often lopsided and sometimes grave sins go unpunished).

Sometimes hope isn’t readily available, in other words.

But, when the audience was my kids - looking up trustingly at me — it occurred to me that maybe the first job was to underscore that, as bad as things sometimes got, the world was ultimately workable; things could, with their help, every now and then, turn out well, or at least better. (That they were, in Tillie Olsen’s coinage (that we all are) “more than this dress on the ironing board. helpless before the iron.”)

In other words, I gave myself permission, with this story, to let things turn out well, in a way that, at the time, I was not doing with my adult fiction. In fact, I sort of required if of myself: “Do what you have to do to make things turn out OK in the end. But: do it in the least-false way you can.”

Which turned out to be kind of a revelation for me as a writer. Because, with this self-admonition, I was essentially saying, “Since you know there are positive forces in the world, you ought to be able to make them appear in your work, or else you’ve got a technical problem on your hands. You’re in the thrall of a blind-spot being created by habit.”

In those days, with my adult stories, I was working hard to avoid falsely happy endings, in which a desire to be optimistic overrode the potential of the story.

With The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, I was trying to avoid a falsely negative ending – one in which my desire to be hip or edgy (or consistent with what I was doing in my adult stories) overrode the potential of the story.

These days, I don’t steer either way. I just keep pushing the ending out and out (happy and sad and happy again, over and over) until it seems that the story has yielded the maximum meaning – and then that’s it. And then I say to myself, “OK, having gone through this rigorous process, this ending that you’ve finally settled on must be the truth that this story wanted you to illustrate. It’s not the only truth, but it’s the truth this particular story had in mind.”

If it's "happy," great. If it's "sad," also great. Because the world is, for sure, both of those, depending on where we happen to be located within it.

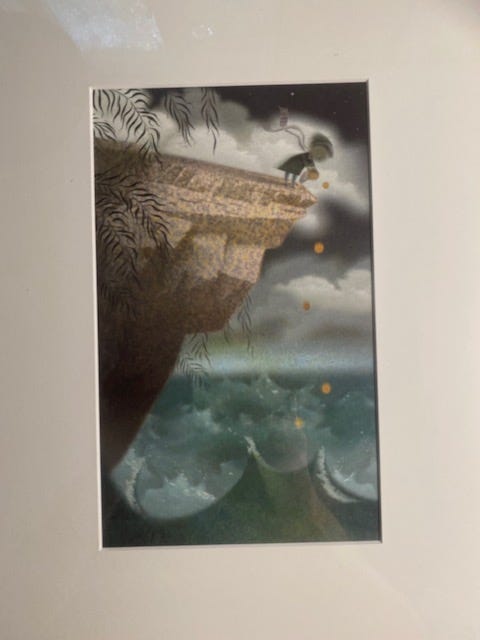

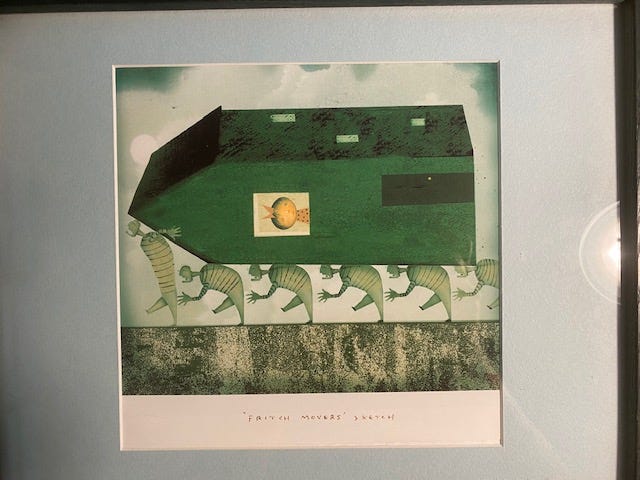

I sent the book to my editor at the time, Daniel Menaker (may he rest in peace) and he liked it but he seemed a little iffy about whether the market would, you know, bear it. It was a weird length for a kids’ book, it did have a bit of a darkness about it, and I had no track record in kids’ books (and just one book at all out at that point). But he said he’d send it around. And then – on a day that still lives on my short list of really, really good days – we heard from Lane Smith – the great Lane Smith, who’d just published “The Stinky Cheese Man,” which had been designed by the great Molly Leach, and the two of them just happened to be married, and Lane and Molly said they’d like to work on it.

And just like that, we had a book going.

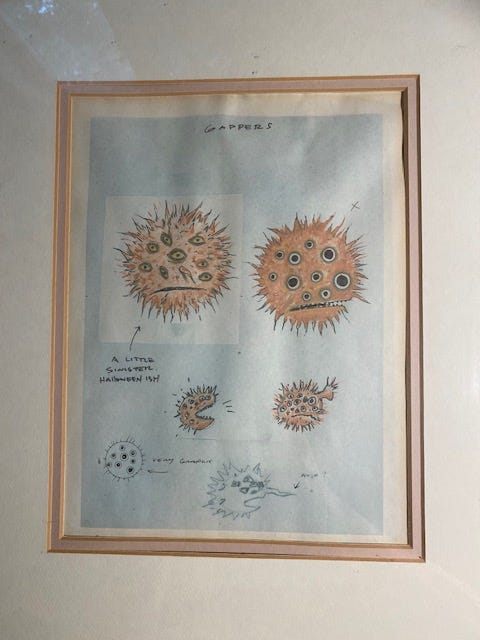

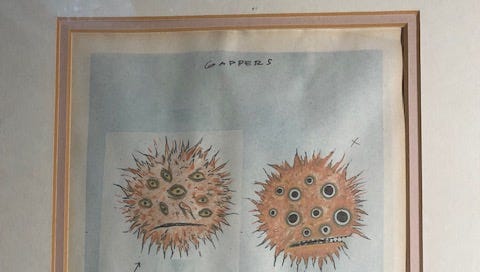

I remember being in New York, in their studio, about ten days later, expecting to just have some general talk about the book, and finding an entire huge wall covered with brilliant, thrilling, sketches and paintings – all of it done in ten days. This was a big artistic moment for me. What I took from this was the notion of profligate, joyful production – the sense that Lane was able work at this very high, exploratory, pitch, without neurosis. It wasn’t being eked out of him, it seemed, but was being produced spontaneously and happily. He had access to a crazy level of creative energy. The work - the vibe in the studio - was celebratory.

This little voice in my head said, “Aha! It’s OK to allow yourself, in certain periods, to overrule your dogma about working slowly and carefully and just accept the fruits of the subconscious – this is also a way of working. You can, in fact, work both ways - you can work in any way. Accept all ways - accept all gifts of the subconscious.”

I’ve kept that in mind ever since, this notion that, although we might have ideas about how we work, we wouldn’t want to get too attached to them, lest they start interfering with how our subconscious, in some new moment, might suddenly feel like working.

In such a moment, the subconscious is offering us a gift and we need to be ready to accept it.

So…thanks Lane, thanks Molly.

I haven’t written another kids’ book since, really, unless you count Fox 8, which I don’t, I don’t think.

I had an early version of that story, that I wrote per the above ideas, thinking it would be for kids – it had a happy, uplifting ending – but the editors I sent it to didn’t like all the misspellings.

So then it wasn’t a book at all, but a bunch of pages looking up at me, like: Any way to save us? Get some use out of us?

And so I recast it, in my mind, as an adult story, which meant that I removed the compunction to end it happily.

I just let it go where it wanted to go.

Which was…somewhere dark.

I still try to advise anyone buying that book that, though it looks and sounds like a kids’ story, it isn’t one.

Well, or maybe it is.

I guess it depends on the kid, to some extent.

But there's a harshness and a violence in it that I wouldn't have put into one of those stories I told our girls back in the day.

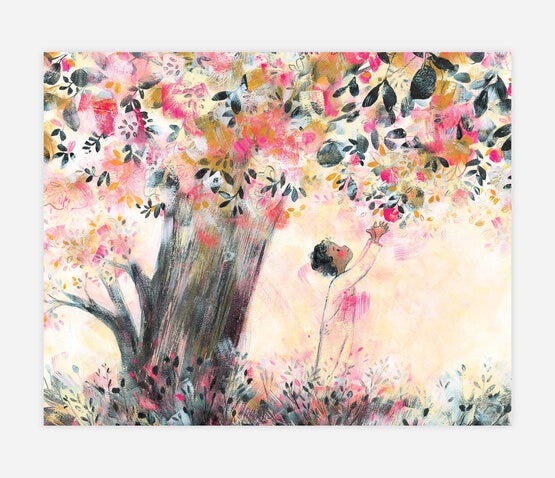

Now, I want to reveal (with her permission) that the person who sent me this question is the incredibly talented kids’ book writer Corrina Luyken, the author/illustrator of (among many other books), ABC and You and Me; The Tree in Me (an NCTE Notable Poetry Book and Indie Bestseller); My Heart (A New York Times best seller); and The Book of Mistakes (which The Wall Street Journal called “sublime”).

And I thought it might be a great Story Club opportunity to turn the question around on Corinna and ask how she approaches endings, in her books, and what she thinks of as the purpose of literature for kids.

Corrina generously agreed to respond, and here’s what she said:

George,

Thank you for this. It’s interesting to hear that “Gappers" began as an improvised, spoken story. It has a rhythm and sound quality that begs to be read aloud, so I’m not surprised.

Before I weigh in on endings (something I’ve been puzzling over lately) I want to say that I still, vividly, remember reading “The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip” for the first time. I'd just graduated from college and was visiting a bookstore where I used to work. When I asked the manager what she thought I’d like, she handed me a tall, thin book. It had large orange type on a translucent velum jacket— through which you could see traces of art on the case below. It was unlike any book I’d seen.* After I read it, I flipped back to the beginning and read it again. And then, again. I remember thinking something along the lines of “wait, you can do that in a children’s book?” By which I meant that it was, as you put it, 'kind of a weird length for a kids book and it had a bit of darkness about it'— which I loved. It was strange, sad, funny, hopeful, and true. It was beautiful.

Which is to say, that although there are many other books that I adore, that have guided me on my path to becoming a picture book maker, “Gappers” was one of the very first. And “The Book of Mistakes” owes a great debt to “Gappers”— so, thank you.

As for endings—

I asked this question, in part, because I am working on a project with an ending that is a puzzle.

One of the great joys and struggles of being an author/illustrator is that when a story is stuck, you can’t always tell if it’s the art or the words (or both) that are the problem. The flip side is that you get to problem-solve from multiple directions. It’s more complicated, and you can get yourself into a lot of trouble, questioning everything— but the process can also lead to surprising solutions that you wouldn’t find any other way.

My current project/challenge is a picture book about a group of people who love to argue. The original ending was not particularly hopeful, and almost everyone I shared it with (all smart people) kindly suggested that, because picture books are for children (though I would say that they are actually meant to be shared) perhaps the ending ought to be at least a little hopeful. Since that feeling of hope was intentionally absent from the words, I figured the solution would be in the art.

But forcing hope into an ending doesn’t really work, right? And so— hopeful ending after hopeful ending fell flat. Eventually, I abandoned hope and began searching for other satisfying (if not hopeful) ways to end the story. I turned toward humor (which had been a large part of the story all along.) But humor, alone, wasn’t working either. And so, I have puzzled over this ending… for years.

But recently, through a series of small changes to both the art and the words, this project has shifted. And in the newest version, there is hope. But I would call this hope more of a temporary resting place, not a final destination. Which is not unlike how you described your current approach to ending stories, one of “pushing the ending out and out (happy and sad and happy again) until it seems that the story has yielded the maximum meaning.”

I would even say that this description is very similar to what you did in “Gappers”. You gave us hope, starting with “And life got better. Not perfect, but better.” And then, on the following page you allow the story to unfold a bit beyond that. You complicate things. And this complication, while absurd, feels honest and true.

Maybe that’s the thing about endings and hope. About hopeful endings. In order to feel truly hopeful, they must first feel true.

Which is not easy to do. It’s one reason why I love “Gappers”. It’s also why I appreciate reading your thoughts on dissatisfaction, on revision, and on endings.

The arguing project, when I finally get it sorted, will be my eleventh book. But it is only the second to give me so much trouble with the ending. The Book of Mistakes, my very first book, was the first. What I can see now, is that having a tricky project early on was a gift— because now this puzzle, this process of not quite knowing, of trying to find my way through a story without a clear sense of where it is going… is, if nothing else, familiar.

I have a big black cabinet in my studio where I tape up quotes, reminders for when I’m feeling lost in the process, deep in the thicket of not knowing where I’m going. One of them is by Tove Jansson — “Every children’s book should have a path in it where the writer stops and the child goes on. A threat or delight that can never be explained. A face never completely revealed.”

I love this. And I find it to be true of the best books. Next to this quote is something you said— “in the end, making a piece of art is very difficult, and takes all that we have— the rational, yes, but also the part of us that knows how to get into trouble, and the part that yearns for mystery, and is willing to go out beyond the safe and habitual and easily justified to get it.”

Which sums up, quite nicely, where I am— waving hello over here, way out in that mystery… slightly uncomfortable, and appreciating (greatly) your thoughts on this beautiful mess that is the creative process.

Appreciating the reminder that we’re not, any of us, alone.

As for the purpose of literature for kids—that’s easy. I also keep a quote by Kate DiCamillo next to my drawing table. She says it beautifully:

“We have been given this sacred task of making hearts large through story… we are working to make hearts that are capable of containing much joy and much sorrow, hearts capacious enough to contain the complexities and mysteries of ourselves and of each other.”

What a gift it is, to do this work,

Corinna

p.s.

Capable— what a beautiful word! It would make a nice name for a character in a book, don’t you think? Perhaps someone smart and slightly reserved, who is looking out for the (less smart, less reserved) people around her?

Thank you so much, Corrina.

Here’s a wonderful article about Corinna and her work, with plenty of beautiful images. And here’s another.

Her website is: www.corinnaluyken.com

Here’s the lovely cover of The Tree in Me:

Over behind the paywall, we’re doing some work with prompts. Join us, if you want:

MY HEART. Thank you both. I bubble over. I have been a published children's author for 36 years. ( Canadian

not in the US (: ) too bad for royalties but no matter I am now signing books for a third generation. This boogles the mind. I often think of how my life is so full of love and kind people because of the path I chose. When I went to grad school to study the literature I thought profoundly important there were still circles in academia that called kids lit-- kitty litter. Yet there have ever been the champions! E.b. White a hero ! A book can't be a book unless it's read and it takes a lot of people who care enough about children to put excellent books in their hands. And invite authors into schools etcetc. The teachers and librarians are the superheroes. The parents and grandparents too. In case I am sounding too fuzzy wuzzy here I am writing a novel with a childrens author/ storyteller as very flawed protagonist who is told it's a bunny eat bunny world. She says no way. She finds out a lot as she ages but is she is a child who lived undercover as an adult? I'm kidding. Maybe.

William Steig said children's literature is largely a literature of optimism. I think he is right but my hopeful ever after has changed..they lived after works too. So many exciting children's books. that is where I look for wisdom. Ever after is nice for the grown ups too. Especially those of us who know certain rabbitholes can be dangerous. The chain of book being in kids book world does make you see interconnectedness of being on a level and frequency I wish more of the world would spin on. I think we could change the world one children's story at a time. Story not book. The oral tradition and human voice have so much to do with why it is so powerful. The emotional connect so deep . If grown ups would only keep reading outloud to each other every night. (: I run a small seasonal book shop and I know I'll order your books for shelves next year. I BABBLE I do but thank you thank you both so much for this. This was serendipity. Needed. Sometimes things do come in a first burst but only once have I not revised. Today before reading this I found an ENTICING ending to a children's story I started over 20 years ago. Enticing ! It surprised me. THRILLING! That shiver of knowing. But still that wee voice : Who does that kind of thing ? I asked myself. . Spend years on such few lines. Then I came here. Answer : People who create to hold hope in the world of darkness by the very act of creation. They've met the beauty and the beast. And yet want to share a kind of ... joy? No small miracle me thinks. Creating magic and Wonder. Light. That is why I come here. This post is sooooo beautiful. . I am biased. I'll stop now. Heart Great Full. Now I mean. Now.

Like Jeremy below - this book was the book that brought all your other work to me. My daughters who were really young at the time - just 2 and 4 - saw the book on a bookshelf of the now long-gone Borders in Philadelphia. I thought it was going to be too long for them, but they insisted, we bought it, went right home and sat on the couch and I read it to them. Well, the 2 year old did get up and wander around, but my four year old sat and listened to the end. Then she drew some gappers which we put on the fridge (wish I still had that drawing, but alas...). They asked for it again and again throughout the years, and we got so chunks were memorized. When they learned to read, I often found it splayed open on a bedside table. Now my girls are 24 and 26 and they remember your book clear as day. Both my girls are deep readers - but my younger daughter has read your short story collections as well as Lincoln in The Bardo - and loved them both. But The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip remains to this day as her favorite in the Saunders oeuvre.