This week’s question is a long one but, I think, well worth it. It’s articulate and detailed and describes a dilemma I’m guessing will be familiar to many of us. The questioner graciously said that I could cut it down as needed, but I like it at its full length:

Q.

In the past, you've used the sentence "Jane came into the room and sat down on the blue couch" to demonstrate how a kind of granular attention to diction can move the Positive/Negative meter on a word-by-word basis — asking which words earn their place — whereas at other times, this meter might apply to larger units of text, or even "moments" more loosely defined.

Combining this idea with one of your other insights about how "voice" can emerge organically from scrupulous line edits, I'm wondering how you negotiate another hypothetical meter: namely, the "Poetic/Prosaic."

Recently, you've discussed how certain early influences (e.g. Hemingway and his pugilistic simplicity) prevented you from playing around with language and unleashing your characteristic humour, and now you're "tossing M-80s in the direction of the henhouse, putting spiders in Aunt Janet’s slippers."

In my own work, I sometimes struggle with the feeling that I should simply "turn the dial up" on my prose in order to make it more golden, like a piece of toast in the toaster, forever verging on burnt bread. Last year, when I read Paul Lynch's Booker-winning Prophet Song (2023), I was impressed by how straightforward his sentences are, in that "get out of the way of your own story" mode of writing. It has that "spoken" feel, with the sculptural beauty of Don DeLillo's prose (clearly an influence of his), but the sentences are longer and lighter.

All to say: like younger you, I feel enamored of this style of writing and the apparent "maturity" of it (as in, I could show off, but I won't). And yet, simultaneously, I'm worried that publishers will mistake my attempts at restraint for lack of craft, and so I reach to turn up that dial again and again, when I feel like I should be solving some issues by other means (i.e. even if the story sucks, at least they might like it because it reads nice).

Maybe an example or two of the Poetic/Prosaic meter in action would be useful. Take this sentence from Lorrie Moore's I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home (2023): "The wild-eyed varmints in the traps are past wailing, and the nightjars whistle their hillbilly tunes." And now compare this to a passage from Claire Keegan's Small Things Like These (2020): "On the street, a dog was licking something from a tin can, pushing it noisily across the pavement with his nose." For me, the poetry dial swings to 83% on Moore's sentence, and maybe 51% on Keegan's, although they are both golden in their own ways. Then there's one of Lynch's sentences, such as: "A bicycle courier slows to a red light between traffic and balances to a standstill without resting his feet." At first glance, this registers at about 27% on my poetry meter (though there are some sneaky things going on with bicycle/between/balances). None of the words is that fancy, but the image as a whole is precise, original, well-observed.

Getting to my question now: what's your relationship like with the impulse to impress? Clearly not every clause needs to work that hard, since even a Booker-winning novel contains thousands of utilitarian sentences like "He sits down and stares at his hands." But what's the secret to striking a balance between the banal and the beguiling?

If I encountered a sentence like "Jane sat down on the blue couch" in my own writing, my tendency would be to habitually edit upward, searching for a shiny detail to catch and reflect a bit of light (but not too much). I sense that this is your approach, too, since one of your stories, "The Mom of Bold Action," contains the following sentence: "Then he collapsed on the couch, burst into tears. His face went all shrivelled-apple and he started soundlessly and in slow motion pounding his fist into the arm of the couch." Clearly, "went all shrivelled-apple" is doing the most work in this sentence to keep the reader in the Positive zone, since the syntax is delightfully askew — mirroring the syntax of his face, etc. You used the word "undeniable" in another Story Club post (August 4th, 2022) to describe some sort of consistent effect that the words have, and it feels like the shrivelled apple is one of those moves of undeniability. Is that fair to say? And does this feel like an iterable technique? An apple per page keeps the reader engaged?

Reading as a writer, I tend to bank these moves away, so that one day I might describe a crying eyeball as an eye-turned-squeezed-lemon or something. My follow up question would be: do you also bank away these moves (qua moves) in note form, or do you just let it all filter through your subconscious? Some of these micro-strategies feel like the real alchemical secrets that novice writers, like me, are trying to suss out.

A.

Yes, and thanks for the excellent and precisely stated question.

Let me see if I can be helpful.

I think the simple answer to “Poetic or prosaic?” is: “Well, right, exactly, that’s what each of us has to decide for ourselves, in every sentence.”

That is: this kind of thing can only be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Otherwise, we’re on AutoPilot.

We can’t, and wouldn’t want to, have a general take, or a usual procedure, or a default approach. These are ways (in my view) of avoiding the actual artistic act, which involves making a specific choice at specific places in your text.

We have to be, in other words, alert to what’s needed here, now. That’s our job: to decide and decide and decide, in a context-reactive way.

“O.K., George,” I hear you saying, dear Questioner. “Nice evasion. But how might one go about choosing how prosaic/poetic to be at that given place?”

Well, right, good question.

First we might ask: What’s the underlying purpose of the sentence? That is, what is the sentence there to do, really? What is this section of the story doing? What part in that purpose is this section playing?

Using the example you cited, from “The Mom of Bold Action” (page 83-84 in the US edition of Liberation Day):

"Then he collapsed on the couch, burst into tears. His face went all shrivelled-apple and he started soundlessly and in slow motion pounding his fist into the arm of the couch."

This bit, in the context of the story, is doing some particular work. It’s basically there to make you believe that this violent attack this husband has just committed (against a person who he believes has harmed his son) has really cost him something – this kind of violence is new to him, not something he’s at all comfortable with.

So, my job, in this series of sentences, was to get this across in a vivid way that the reader would accept.

I could have just said: “He was really damaged by what he’d done.”

What I’m looking for in a moment like this is increased specificity. Specificity does two things at once: it convinces a reader and makes the sentence better. (These are really two ways of describing the same quality, if you think about it.)

So, I’m trying, on the sentence level, to get the most specificity in there without overdoing it. I’m sure we all know the feeling of wading into a sentence that is just…too much. It keeps us from seeing the thing described and we often feel, behind the sentence, Writer Writing. (There’s a Chekhov quote to this effect, that I can’t seem to find – but he talks about “The man sat in the grass” vs a much more detail-rich and long-winded version that would be difficult for a reader to imagine.)

The sentences I wrote seem to me more alive and more convincing than the “prosaic”: “He collapsed on the couch and started crying.” They also seem more alive and convincing than the “poetic”: “Collapsing akimbo on the rattan pseudo-Stickley, he began to resemble some fulsome toddler denied his heart’s fondest desire.”

The first doesn’t do enough and the second does too much.

Like the Three Little Bears, we’re looking for “just right.”

There’s also the question of voice. Who’s head are we in? Who’s speaking/thinking? (In the case of “The Mom of Bold Action,” the story is what I think of as “third-person ventriloquist: a close third-person suffused with the mother’s voice and attitude.)

Would that person tend to be more poetic or more prosaic? Would the character think this way or that way? Is her language simple or complex? If we choose to, in places, violate her diction (decide to get fancy), does the payoff justify the violation? Is there a case to be made that writing out of her syntax is actually the best way to represent her true presence? (In the “Mom of Bold Action,” this mother is a writer, and so for her to be a little extra-descriptive there made sense to me – I felt like I could “allow” her that bit of flamboyance reflected in “went all shriveled-apple.”)

If we’re using an omniscient narrator – who is he? What can we convey by way of his voice? Might his voice want to modulate a little, just here, or just there, to convey….something or other? (The mantra here might be: “use, use, use” – that is, use every aspect of the story to convey additional meaning.)

We might also think about pace. Do we need to be speeding up here, getting the reader more quickly to some important payoff? Might we want a little pause? One way to induce a slight pause is with a sentence that takes a split-second more to parse, i.e., a more poetic/”fancy” sentence.“1

And there’s rhythm to think about; five difficult, “poetic” sentences in a row might want to be followed by a crisp little sentence of the “Jesus wept” variety.

You mentioned the fear of “showing off” and this resonated with me, for sure.

I sometimes think of this in terms of readerly engagement, as follows:

If the reader feels that I was showing off for showing-off’s sake: she feels neglected and switches off.

If, on the other hand, the reader feels that I am under-inhabiting the fictive moment by erring in the direction of a frugal, cautious, unfelt simplicity (or that I’m rushing through that beat without really dwelling in it): she (also feeling neglected) switches off.

I’ve noticed an interesting thing about these binaries that often show up in craft discussions (poetic vs. prosaic; experimental vs. realist; serious vs funny, and so on) and which have the potential to freeze us up, by making us think that we have to decide and choose.

One thing we can do when confronted with one of these Obstruct Binaries is: blow the thing up. That is, abandon it in the service of some higher criteria; find a more profound basis on which to decide.

So, as suggested above: we could put the poetic/prosaic binary aside and think, instead, about the purpose of the sentence, and/or the point-of-view, and/or the pace, and/or readerly engagement.

Of course, what we’re really going to do is…think about all of those at once. And “think about” isn’t quite right. We’re going to feel them all at once and do that most important artistic thing: make a split-second decision.

Then sit with it awhile. (Until the next time we read it. And then we’re going to decide again, by either leaving it be or changing it.)

The point is that every sentence produces an opportunity of us to be more present in our work of art – more narratively alert.

Imagine you had just one hour to be with someone you loved before they left town for a year. You’d want to use every moment of that hour to demonstrate your love. But…this would take some thought, some engagement, some presence.

If you just kept shouting, robotically, “I LOVE YOU,” over and over for the whole hour – not great. (Your loved one would feel….neglected, not seen, objectified.)

So, you’d want to be tuned in at all times, constantly asking: “How might I best demonstrate my love right now, given what’s actually happening in this moment we’re actually in together?”

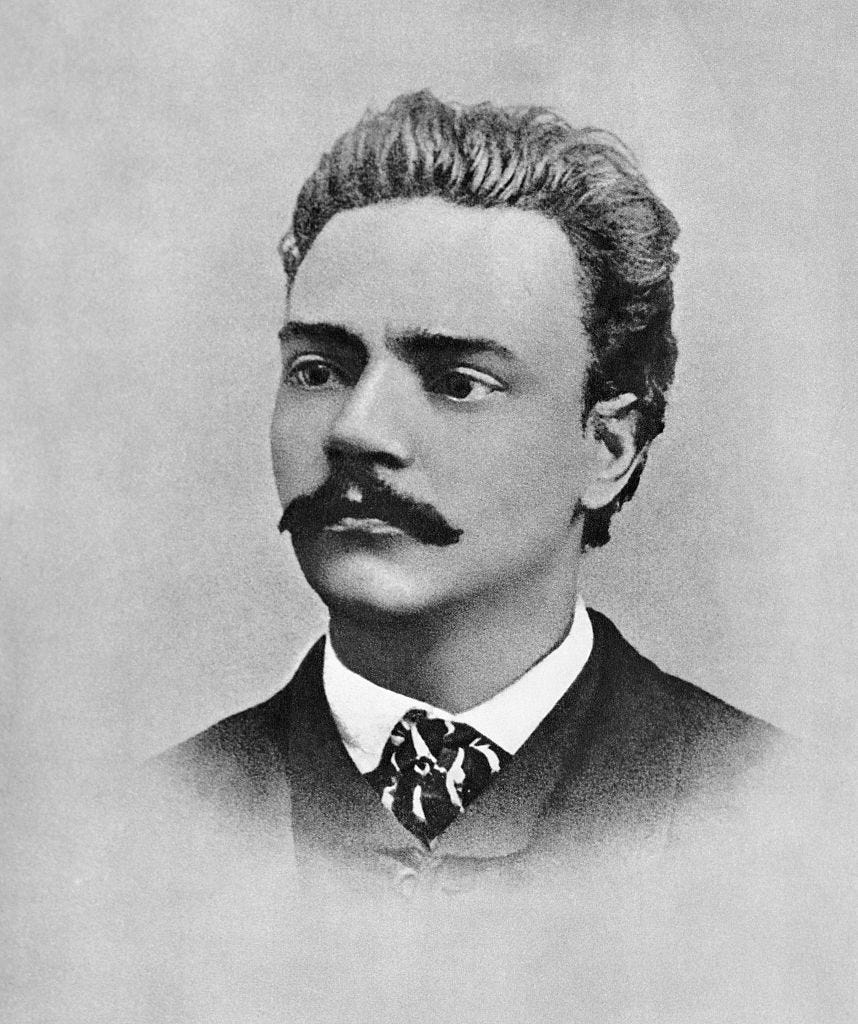

My wife, Paula, and I went to see the LA Philharmonic at Walt Disney Hall on Sunday and heard an incredible rendition of a favorite of mine, Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony. We were seated in the second row and what struck me was the extreme amount of motion within the orchestration – phrases being exchanged between sections of instruments, sections being subdivided, themes being thrown back and forth across the room. All of this produced the sense of hearing a spirited, intentional, conversation. No part of that orchestration had been phoned in. I could feel Dvorak making decisions (informed decisions) in every single line. It was, let’s say, a masterpiece of non-randomness – or, we might say, a masterpiece of mindfulness. Dvorak was present, in choice after choice. The effect was dynamic and emotional and breathtaking, especially, I think, because Gustavo Dudamel (the legendary conductor) and the orchestra seemed to be “in on” those decisions – they were aware of them and feeling them and adding to them by making, or having made, decisions of their own.

So, you know: bravo.

The piece was, in other words, decision-rich. Dvorak didn’t seem to have a rigid operating theory about orchestration or a credo – rather, he seemed living and present in every phrase, choosing, choosing, choosing, and the resulting work of art sounded like a living, breathing record of all those decisions; it sounded like a human mind, thinking, caring, celebrating.

You could see the effect this had on the audience; contrary to convention, there was applause between every movement.

It brought us all alive, in other words. And what brought us alive, in part, was Dvorak’s living presence in the score.

Alertness from beyond the grave, truly.

How does this relate to the question?

Well, in writing, as in the Dvorak, we don’t get to have an overriding, locked-in theory (on orchestration, on how prosaic/poetic to be). That would be too easy (and then anyone could do it, ha ha). But also: the audience knows when something has been too neatly decided in advance (that is, in advance of the presently occurring artistic moment) and would recognize this as a form of fakery, maybe, or coasting – as a failure in intimacy between artist and audience; a form of condescension or absence.

The audience might feel: “Hey, this artist keeps making the same decision re poetic vs. prosaic in every damn sentence, no matter what. He’s like a mechanic with just one tool for every job. He’s not really here with us.”

What the audience loves is the feeling (an illusion, of course) of being present, there with the author, as these decisions are being made. That is to say: they love the feeling that the decision is being made in lively response to the text at-hand.

Worker: What tool should I use?

Maestro: Well, what’s the job?

So, as Dvorak was demonstrating from beyond the grave, we never want to go on auto-pilot. Every sentence is a chance for us to be intentional; to demonstrate our thoughtfulness and our presence and our commitment to a reverent artist/audience relationship.

What a joy and what an opportunity: all those hundreds of sentences in a story, for us to precisely calibrate, and thereby infuse with essential “us-ness.”

If you were my student, dear questioner, I’d ask you to choose a certain sentence in a particular story of yours, and talk me through some different options. What’s your “poetic” version? What’s your “prosaic” version?

Then I’d ask you to talk about the work that section of the story is meant to be doing. I’d ask about whose head we’re in, if anyone’s. If not, I’d ask about your omniscient narrator: what’s his deal? Does his voice want to change over the course of the piece, modulate, in order to communicate meaning in some way? If so, what moment are we at just now? What does the story require of the voice?

In short: what are the opportunities presented here (right here) to make your story mean more, and more ecstatically?

Another maestro, from another time, same piece:

P.S. Re the last paragraph of your question: No, I don’t, as you put it, “bank those moves away.” I used to do this. (In a notebook or on scraps of paper I’d eventually lose.) But now I feel that the fictive moment is going to call for….what it needs.

I trust that, when I get to sentence 88, just having read the previous 87 sentences, my mind is in a high state of alertness and engagement with the text and it knows what it needs - which will, odds are, not be in that notebook or on one of those scraps of paper.

That is: if I just drop in some earlier-generated (to use your metaphor) “chunk of gold” into an unsuspecting story that isn’t asking for it, the story will, understandably, treat that sentence as an intruder, and react against it, and eventually reject it, because it senses that that sentence has no relation to the ones around it. (It’s a random interloper.)

(I do, sometimes, come up with a sentence or two that I like and use that as a starter for a new story, of course.)

So, as above - true gold is that which arises in response to where you are in the story at that moment.

This reminds me of a story I heard from Alan Moore's class on writing. Apparently, Shakespeare, the master of invented vocabulary, used to place his fantabulous inventions right before moments of heightened drama. Per Moore, this let him dislodge his audience's assumptions about the activity taking place, making them more receptive to the story. There are supposedly MRI scans of people reading Shakespeare which light up like a Christmas tree when they encounter these words.

I can't vouch for the veracity of those details, but I think the technique itself is real. It seems to me that when you use more complex or surprising descriptions, you're necessarily forcing the reader to engage more with the text. This is setting aside the aptness of your analogies or the flow of your prose or what-have-you. Rather, it's in the pure and simple terms of demanding more attention to comprehend the language. By adding complexity at the right moment, you're making a request to the reader to dig deeper into the text, to ponder it, and to reevaluate what they have read.

Such a great question and response. I was especially interested in the questioner's observation about the sentence from "The Mom of Bold Action." The questioner writes: "Clearly, 'went all shrivelled-apple' is doing the most work in this sentence to keep the reader in the Positive zone." My feeling is a little different. Just thought I'd share it here in the interests of thinking more about the question of what counts as "poetic" (disclaimer: I'm no poet or poetry expert, but come at this more from a literature and linguistics background). I definitely took note of "shrivelled-apple" since it's such great image, but, I didn't really linger on it. For me, I felt that the word "started" was what did the most work in the sentence. "Started" propelled me to stay in the P-zone and kept my curiosity going. The very word "started" cues or alerts me that something important is about to, well, start. And what starts is what I consider an absolutely beautiful line of poetry: "...started soundlessly and in slow motion pounding his fist into the arm of the couch." Why do I feel like that? For one thing, the alliteration of all those sibilant "s" sounds (partially foreshadowed with the "sh" in "shrivelled": e.g., started, soundlessly, slow, fist. Next the assonant vowels in the following pairs: soundlessly, pounding; slow, motion; started, arm." Third, the rhythm/meter--which I can never remember the technical term(s) for, but I can definitely "hear"--not just with my ear, but with my whole body--in the relationship of stressed/unstressed syllables. There are probably lots of other things going on in that part of the sentence that I'm not noticing yet, but for me, that's the undeniably poetic part of--so skillful, so gorgeous, and I'm guessing, so much work! I know George often talks about making choices and decisions about each and every word, but in this example, I can feel him making choices and decisions about every phoneme.