Q.

I’m not a newbie to writing — it’s how I’ve made my living for most of my life (journalism first, then fiction including writing for TV professionally and also publishing two detective novels now out of print, short stories and essays). Without sharing too much, I stopped writing due to a variety of reasons, but mostly around personal trauma. I’m now trying to write again. I started with small steps — your exercises, reading good books and writing journal entries and short short stories. Now I’m tackling a bigger project. It’s the best idea I’ve ever had and it’s really helping me break through the myriad of reasons I’ve given myself for not writing for literally years.

The more I dig into it, the more it’s telling me it can't be told from the point of view of just one of my characters. Each of the major characters (three at the moment) and possibly two ancillary minor ones need to be heard from and not just heard but seen and heard — that is I think we need to hear what they’re thinking and see what they’re experiencing from their POV. Up to this point, almost everything I’ve written has had a single narrator either as first-person or omniscient.

As it happens, I’m reading Moby Dick for the first time and for sure, we hear from many different characters and this seems like how I might have to tackle my story. I was hoping you could give us guidance in telling stories from multiple POVs? Are there rules? Can you share a favorite example or two? What are your thoughts about it? Is it something to be avoided or do you see it as a legit path to follow when you think it’s needed? In discerning whether your story is up to the task, what do you consider?

Thanks in advance for any advice and guidance. I haven’t been participating on Story Club lately except as a lurker. That’s because I’ve been writing and I’m writing in large part because of Story Club. It’s such an amazing resource and it has been incredibly helpful in getting me back in front of my computer. I am grateful beyond words. It is like having an advance writing program, reading group, mentor, teacher and fan club all in one spot. If the Internets were meant for anything, this feels like one of its higher purposes. Thank you!

A.

Well, first, thanks very much for that cluster of much-appreciated compliments there at the end. I really do see this as a natural outgrowth of my teaching and glad, for sure, if Story Club had anything to do with getting you back to writing again. And I’m sorry for that trauma, whatever it was, and glad, very glad, to be part of the process of recovering from it and reclaiming your art form. Hooray for the courage and resolve that must be taking.

I took a rough swipe at this question here, a little while back. There’s also an embedded mention, in that post, of another, on “The 1200-Page Elephant” that might be helpful.

But to expand on this a little:

Here’s what I think is an important principle: whenever we find ourselves seeking a set of rules or some guidance on a matter of art, we should remember that the reader is hoping for our unique take on the topic. She’s looking for us to solve the problem or answer the question in a way that 1) suits the surrounding work and 2) is, as much as possible, original to us and organic to the work.

She wants to know: How do you, Dear Questioner, approach the question of multiple points-of-view? And why?

There is no right answer (no rules) but she wants to feel that you have closely considered this issue, as one possible way of charging your story with more meaning and intention.

So my short answer to your question about multiple points-of-view would be: “Yes, good question: what do YOU think?”

And a good way for you to answer that question – the only way, really – is for you to get into the manuscript and see what excites you. Is there a particular frisson at a place where Character 1 yields to Character 2? Are there moments you’re creating that wouldn’t have appeared without different viewpoints? What rules do you find yourself drawn to and internalizing, just by taste? And here I’m talking about that delicious, inexplicable, almost naughty feeling that feels like, “Just because I want to, and it delights me.”

So, as far as rules about POV: no. I don’t think so. Or: there are only the rules we discover for ourselves, while seeking delight.

But there are, let’s say, laws – that is, there are ways in which things tend to work. (Gravity is not a rule, it’s a law – we may not like it but it still applies.) We aren’t bound to these “laws” but if we work in opposition to them, or if we ignore their existence we will, let’s say, pay a price in readerly attention.

We can all likely posit some of these “laws” just by watching ourselves read.

Here are a few that I’ve internalized regarding point-of-view shifts:

1) They cost us, just a little, in that moment where the reader has to come out of one character’s viewpoint and make the move into another. (Is that O.K.? Of course. But it IS a cost…)

2) So, therefore, I almost always start out by assuming that the default story is in one point-of-view, and only go outside of that POV if I feel I really have to. That is, with a few exceptions (Lincoln in the Bardo being a big one) I don’t usually start a story thinking, “This will have three narrators.” That is, my preset is slightly against point-of-view shifts.

3) I try to be careful that I’m not switching POV just in order to avoid narrating something, or to be flashy. (I sometimes see this avoidance in student work: about the time the story wants and needs to escalate, and is approaching a tricky decision moment, the writer will get shy and bolt off into another POV. The “just-to-be-flashy error manifests in a feeling that nothing is really being earned by the POV jumps, but that “cost” still applies.)

4) I’m on the alert, once I introduce a second (or third) POV, for the ways in which the sections want to work. When do I go from one character to another? How much seems to want to happen in each section? And so on. In other words, I am waiting for the story to tell me its rules. It teaches me this by being fun (lively, cool, surprising, delightful) in some places and not in others. Once I get a nice effect by a certain move - that move is a feature of the story and will tend to reoccur.

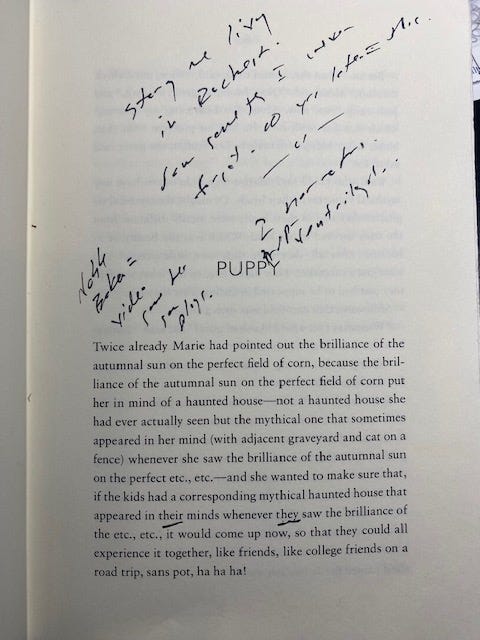

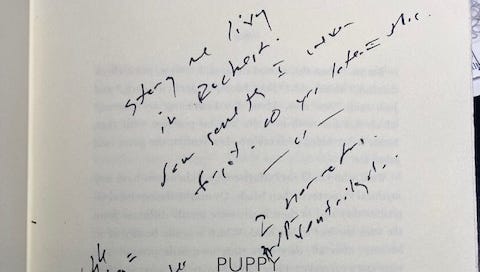

You asked for examples. One that comes to mind is the story “Puppy,” in Tenth of December. It starts in the point-of-view of a suburban mom, Marie, who is driving over, with her kids, to buy a puppy.

I knew, when I started the story, that she was eventually going to find, at that house, a little kid harnessed and tied to a tree out in the yard. (I knew this because I once saw this exact thing as I drove by a house in Upstate New York and that was my entry point to this story – the reason I wanted to write it. We were out for this very happy family day at a lake, in a new car, no less, feeling very high-functioning and on top of the world (that is, I was in a very Marie frame of mind) and then…we whizzed by this kid, in a yard. He ran across the yard joyfully, got yanked back by the chain, sat on his butt, happily got up and did it again….and then we were past, and gone.)

It soon became clear to me that there were two possible ways to introduce this strange, confusing, shocking image: 1) show it first, then let the story explain why it was happening, or 2) let the story explain it, then have Marie see it.

I can’t remember if I actually tried it the first way or just mentally tried it and felt it would be too difficult. In any event, what I did was start the story in Marie’s head and, in order to soften the blow of that image, have us first see it (in the second section of the story) from the perspective of the little boy’s mother (Callie). To her, harnessing the boy like that is not abusive, but a good thing (for reasons explained in the story). She perceives herself as “solving” a problem, of giving her child his freedom, of keeping him from getting killed. She doesn’t overtly say “he’s harnessed and tied to a tree,” and we don’t see that, because this isn’t how she sees it. She’s used to it, she’s already rationalized it.

So, by the time Marie sees the kid (in the story’s third section) she, and we, have more or less been prepared to see it. It lands on us a little more softly and is a little bit easier to digest and to believe. We aren’t thrown out of the story, by shock or by a suspicion of sensationalistic intent - it’s an easier ask, we might say.

And this was only allowed by the point-of-view shift.

So, in this sense, Callie, as a character, was called into being by need. The story needed her to exist, in order to help the reader accept the fact of that harnessed kid.

But again (and again): the above is all just an export of my internalized-by-long-practiced tendencies. There are many great works of art full of contradictions of all of what I’ve just said.

What works, is what we can make work - in our particular mode.

What we can make work has everything to do with what delights us which, in turn, has to do with certain qualities of our mind. How do we plead a case? How do we persuade? By what are we fascinated? What prose effects light us up?

And especially: what problems do we write ourselves into, and what unique ways can we discover to write ourselves out of that trouble?

This, to a reader, is going to feel like originality.

I’m inclined here to end with a prompt, that I would normally frame like this:

How do you, members of Story Club, think about multiple POVs in your work? (And I guess I just did give that prompt, ha ha.) But…

…this is also a moment for each of us to go into a story – one of our own or a published story – that has multiple POVs, and see why and how it works. How does that shift “earn its keep?” (i.e., pay back that “cost” mentioned above?) Why do you allow/accept that POV leap? Or maybe, in some story you can think of (maybe even one of your own!) you don’t accept it. This is a great chance to ask why not.

Thanks, as always, for being here with us.

P.S. In “Puppy,” there are two characters and I write both of them in what I call (as mentioned in the photo caption above) “third-person ventriloquist” – a close third, that tends to be in the voice of the character. But POV shifts can also be accomplished in other ways (as in Moby Dick, which is in first-person throughout, as I recall). The way I think of this is that, when “in” a certain POV, we are restricted to one mind and we see what, and only what, that person can see (and think and imagine and so on). Others may have different ways of thinking about this. As many of you will know by now, I’m not a big stickler on terminology.

Let us not forget the master of the literary pivot, Virginia Woolf, and I highly recommend either To the Lighthouse, or Mrs. Dalloway as examples. This is such a great conversation! But Woolf is a truly one of the first modernists to employ this technique of diving into individual psyches, one after the other. She usually uses some object, say a clock tower (like Big Ben) and then -- since her main characters are either all on various streets being given different views of the clock, or are sitting in their rooms hearing it chiming, the clock becomes the point of pivoting, and it allows her to enter into someone else's head who is either hearing or gazing at the clock, and as is usually the case in her writing, all characters converge physically at some point, such as at a dinner party or vacation house in the Hebrides. She would be a great, and classical, example of how to bring multiple personalities into the mix, and still remain in the third person or omniscient narrator. Just some thoughts from the sidelines today, but I couldn't help myself!

I read the question and what popped up in my mind is War and Peace. I don’t know how Tolstoy does it but he does and it’s magnificent.

And, to address the questioner—great question. Glad you are writing again. I concur with so much you said ,this is like the best workshop, college class, MFA class, writing group, master class rolled up in one. I feel so fortunate to have found my way here.