First, thank you all so much for the wonderful insights and energy you are bringing to the Comments. I’m trying to read as many as I can. But I also think we should recognize that the Comments have two purposes: one is fulfilled when we read a Comment and it light us up; the second is fulfilled when we make the effort to write one ourselves and that lights us up (i.e., moves us further down our own path.)

So don’t worry, at all, if you’re not “keeping up with” the Comments. I doubt anyone is, really.

In other words, if reading the Comments is helpful to you, great. If not, that’s great too. They are just part of our larger mission here, which is to give ourselves an intense interaction with the stories.

I’d also – lovingly, with a smile on my face – say that, if you are doing Story Club during your writing time…don’t do that. 😊 (And this is advice I am trying to take myself.)

Now, back to “An Incident.”

Part of the reason I’m moved by this story is the number of times in my life I’ve held the same defensible-but-deficient attitude as the narrator. If the narrator is a bad guy, he’s a bad guy in the way that all of us are from time to time. It’s a small error that he makes, an understandable one (he’s headed to work, doesn’t want to be late, his attention is focused on the day to come).

The “evil” in this story, such as it is, is correctly scaled, I’d say. In movies, we get leering, totally sinister people, knowing what is right and purposely and gleefully doing the opposite, bwa-ha-ha. But this narrator is behaving badly in a way that feels real to me and has more to do with a brief moment of confusion, during which he is slightly selfish, via momentum and habit, than with some grand evil design. In a sense, he doesn’t really do anything bad (that driver was on his own path, no matter what his passenger thinks). The narrator’s error is sin of omission, a brief, mental error. Which he quickly self-corrects. So, to me, this story says, “You know all that hurtfulness in the world? It starts here, sometimes, with a small, quick bit of mental self-protectiveness.”

The narrator’s bad advice (that the driver should just keep going) is ignored, and life goes on. Well, his does, anyway. My sense is that the driver is going to be in trouble, maybe even jailed. (I’m not sure about this, and maybe some of you who know this historical period in China can weigh in.) In any event, the story seems to indicate that this is a potentially costly decision for the driver.

Last time, I asked you to read “An Incident” again, on the alert for places where the narrator is shaping the narrative or coaching us. As some of you pointed out, “coaching” may not be quite the right word, but for simplicity let’s retain it for now.

Let me show you what I mean, using paragraphs 4 through 13:

Here’s the text, with what I’ve been calling the “coaching” phrases identified and struck out:

We were just approaching S—— Gate when someone crossing the road was entangled in our rickshaw and slowly fell.

It was a woman, with streaks of white in her hair, wearing ragged clothes. She had left the pavement without warning to cut across in front of us, and although the rickshaw man had made way, her tattered jacket, unbuttoned and fluttering in the wind, had caught on the shaft. Luckily the rickshaw man pulled up quickly, otherwise she would certainly have had a bad fall and been seriously injured.

She lay there on the ground, and the rickshaw man stopped. I did not think the old woman was hurt, and there had been no witnesses to what had happened, so I resented this officiousness which might land him in trouble and hold me up.

"It's all right," I said. "Go on."

He paid no attention, however—perhaps he had not heard—for he set down the shafts, and gently helped the old woman to get up. Supporting her by one arm, he asked:

"Are you all right?"

"I'm hurt."

I had seen how slowly she fell, and was sure she could not be hurt. She must be pretending, which was disgusting. The rickshaw man had asked for trouble, and now he had it. He would have to find his own way out.

But the rickshaw man did not hesitate for a minute after the old woman said she was injured. Still holding her arm, he helped her slowly forward. I was surprised.

The result reads like this:

We were just approaching S—— Gate when someone crossing the road was entangled in our rickshaw and fell.

It was a woman.

She lay there on the ground, and the rickshaw man stopped.

"It's all right," I said. "Go on."

He set down the shafts and helped the old woman to get up. Supporting her by one arm, he asked:

"Are you all right?"

"I'm hurt."

Still holding her arm, he helped her slowly forward.

Reading that, what did you notice? As we might expect, the narrator has essentially been scrubbed from the story. This is now a “God’s eye” view of the event – nothing but action, all subjectivity excised.

Now we can see what work that subjectivity was doing.

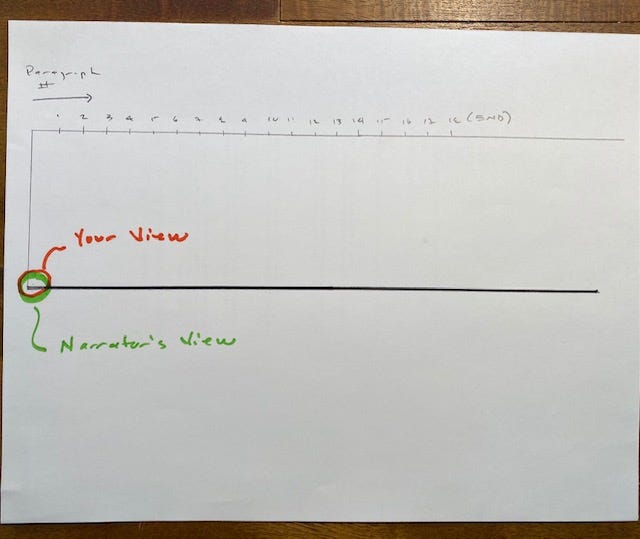

Read the story again, tracking how close you are, paragraph by paragraph, to the narrator. (How much do you trust him? How “at one” with him do you feel?)

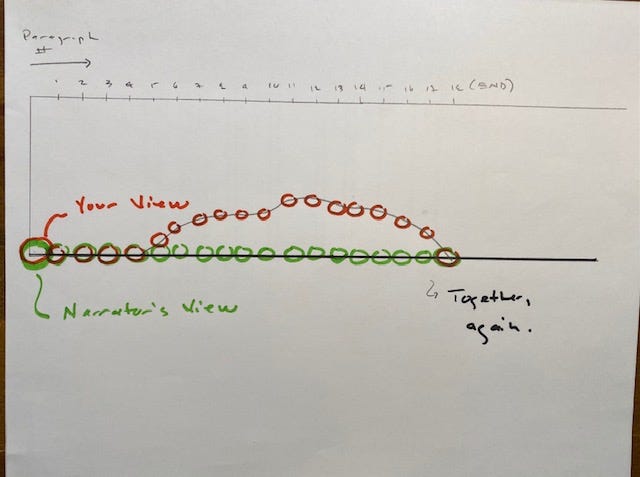

You might even do this by way of a chart, that might start out looking like this:

When you are one and the same, those little circles (one orange, one green) should be on top of one another. As you move away from the narrator (as you feel him as a separate, agenda-having person, i.e., a character in the story) your circle should move away from his.

At which sentence do you first start to doubt him? Why, exactly? How does that doubt develop over the course of the story? What sort of moral complexities is that creating for you?

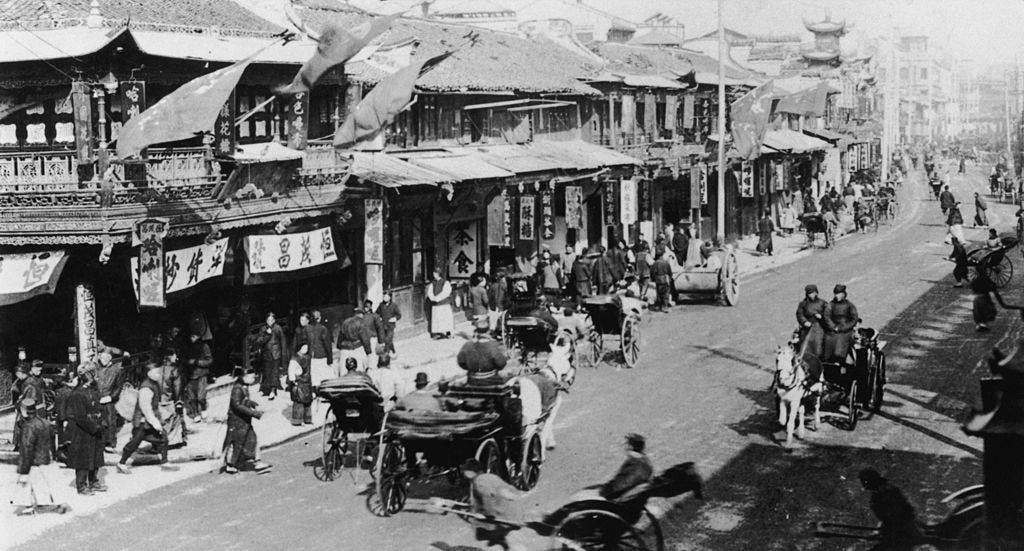

My response below (after you enjoy this view of a Shanghai street scene, circa 1925 - same approximate era as the events in the story):

Here’s my attempt at the chart, with apologies for its, uh, homemade quality:

I believe him (am completely with him) from paragraph 1 through 4 (he gives me no semantic reason to doubt him).

My suspicion (that’s too strong a word, but) kicks in a little in paragraph 5, at the phrase “without warning.” I wonder, a bit, why he’s telling me this. On one level, of course, he’s being a reporter. And yet, once we’ve read the whole story, and look back at this moment, he seems to be engaged with the question, “Whose fault was the accident?” Likewise, when he assures us that “the rickshaw man had made way.” I still believe the narrator but I’m noticing that he is making small judgments that are having the effect of aligning him, slightly, “with” the driver and “against” the woman.

That is, he has an agenda. (All of this, of course, is happening on a very subtle level, and quickly; essentially at the speed at which you are reading.)

Now: paragraph 6, “I did not think the old woman was hurt” – this is the first place where, in my read, the narrator slips over into opinion. (And he’s admitting as much.) This causes us to ask a question, “Well, is she hurt?” The fact that he’s said it this way (“I did not think the old woman was hurt”) has the effect of introducing the question into the story, we might say. (If the car rolls off a cliff and we say to our partner, “I don’t think I forgot to put it in Park,” that has the effect of introducing that question into the story of our trip.)

We’d be, that is, in a slightly different place, if the narrator had said, definitively: “The woman was not hurt.”

So, we might pause here and ask: do you think she’s hurt? If so, why? If not, why not? Where in the text are you looking, to find an answer to that question?

Moving on (still in paragraph 6) we read: “and there had been no witnesses to what had happened.”

Here, I really feel myself separating from (falling away from) the narrator. He’s like a person who says, “Well, I can’t go out with you because my mother is sick. And I have homework. Also, I don’t date.” In that case, we intuit that the person is not being honest with us; what she’s really saying, behind the tri-pointed blather, is: “I don’t want to go out with you.” Here, what the narrator is really saying is: “I want to drive on and get on with my day and not be distracted by this accident, regardless of whose fault it was or if the woman is hurt.”

Sensing his slight dishonesty, we part, slightly, from him. (Again, I’m not saying we’re aware of this – it just makes a little subconscious complication.)

And, to cut to the chase, this dance between reader and narrator continues for the rest of the story.

I’m belaboring all of this to make the point that the story’s power stems, at least in part, from the way Hsun is working with point-of-view, with the dance between reader and narrator, and the energy that results from that dance.

Imagine you’re on a long train trip with someone. In one version, you agree completely with a very honest person who has no agenda. In a second version, you feel that way at first, but then, along the way, he starts saying things that are slightly off, that indicate that you and he are not, after all, in complete agreement. (He keeps trying to position himself in a certain light, or persuade you of something, for example.)

The second trip is going to be more interesting than the first, I’d say – or at least more dynamic. On that trip, you’re going to learn more about who you are and what you believe - by way of your changing relation to him. It will maybe be a more uncomfortable trip, but it will have more energy. Also, you’ll be more implicated, especially if there’s some lag time - if it takes you a little time to understand that you have fallen out of agreement with him.

In paragraph 11, the narrator doubles down: he has seen “how slowly she fell.” She “must be pretending” to be hurt, which he finds “disgusting.”

This, again, makes us turn to the question of whether the woman is actually hurt.

What did you think?

For my part, I’d argue that we actually can’t know definitively, based on the minimal objective evidence provided in the story.

What’s important, in story terms, is that 1) she claims to be hurt and 2) the driver believes her.

This is, for me, the climax of, and the most moving moment in, the story: “But the rickshaw man did not hesitate for a minute after the old woman said she was injured.” It always gets me, the quiet courage and certainty of this man.1

We don’t know – as the narrator doesn’t, and the driver doesn’t – whether the woman is hurt. Nowhere in the story, for example, is there any mention of blood or bruises or broken bones, although there could have been – that is, Hsun could have easily established whether she was hurt or not, with a phrase or two.

But I am moved by the driver’s attitude toward the woman: “If you claim to be hurt, ma’am, I will take you at your word and thereby accept complete responsibility for my actions.” He’s fearless, in my view, this driver, willing to accept whatever consequences his forthrightness may bring. (“Do what you must, come what may,” Tolstoy said.) And we can’t help but contrast this with the narrator’s attitude, which is: “This has nothing to do with me and I’m going to assume she’s faking it so I can get on with my day.”

The narrator is living in the real, pragmatic, competitive world; the driver seems to have some direct connection with the eternal.

But notice that, per the above model, we were, briefly, at first, in agreement with (in cahoots with) the narrator, as he thought badly of the woman.

And this, to me, is one reason the story works – the shifting of allegiance that happens within it.

At the beginning of the story, we’re agreeing with the narrator (that is, we were him; we were seeing things through his eyes). Then, let’s say, we start to feel a little squeamish. The heart of the story lies in our departure from him, our rejection of his position (and, also, the quietness of this rejection – as I mentioned last time, it took me several reads to overtly notice any of this.)

Did Hsun plan this? Did he map out the various coaching phrases he would use, and so on? As a writer, I’d say: No, no way. It’s all more intuitive and instantaneous than that.

We are looking here at what was done, that caused certain effects (the forensic evidence, we might say). But we’re not saying much about the state of mind the writer was in as he did it.

Hsun has one last card to play, over paragraphs 13-17: he has the (current, older) narrator (the person actually telling the story) do a similar falling away, from his (younger) self.

In paragraph 13, we get the first hint of the change wrought in him by the driver’s action: he has a vision in which the driver becomes gigantic. The narrator has “to look up to him” (as he should, we feel; as we, too, suddenly are.) This energy of conversion is then exerted on that policeman; the narrator, somehow echoing Judas, offers him “a handful of coppers.”

By the end of the story, the past-tense, younger narrator has, in a sense, evolved into the older, narrating figure. With whom we, too, are now in agreement. All of us have come to our senses, and here, at the end, all hold the same view of the “incident.”

In my view, it’s this internal liveliness that gives “An Incident” its strange moral power.

So here, maybe, is a story quality we want to keep an eye out for in our future explorations, this sense of internal dynamism – the feeling that a story has “a lot of moving parts,” a sense of internal motion and development, even restlessness.

Everything in a story is meant to move, (or to move on/develop/get more complicated). As several of you pointed out, the wind is one such element; it’s introduced and gets used – Hsun keeps updating us on the state of the wind and this is another thing that makes the story feel dynamic and full of life.)

I’d go so far as to argue that this quality of internal dynamism is one of the most important things in any story, the thing that makes us love it; the source of the actual, visceral pleasure we feel while reading – more so than plot or theme and so on.

One more post on this story, coming on Sunday.

Thanks, again and always, for being here.

Or is he just being obsequious? A cowed person, wary of the law, erring on the side of caution, as he has been trained to do by his authoritarian culture? (In this, the story reminds me a little of “Alyosha the Pot,” which I wrote about in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain.) I don’t think I buy this interpretation, but…?

Can I just say, not for the first time, what a magnificent group this is.

This is a tricky story for me. The man in a hurry is somewhat of a bad man, a bit selfish. The driver is a good man, one who can sleep at night.

At age 16, I was the victim of a hit and run where the driver veered off the country road at me, where I stood up above the culvert by a stone wall. I was still standing as he sped off, but the second I pivoted on my left leg, I crumpled into the ditch. As time went by, it became known who the driver was. Privately, I learned who he had just dropped off and who was still in the car with him. In 1974 the driver was fined $30- for going out of the lane of travel. Me, 3 months in traction and a body cast in the hospital. The leg will never be quite the same. I have noticed that the passengers who never ratted on him had problems with holding jobs, marriages and fought alcohol problems. The driver married one of the occupants, who 40 some years later was hit by a car and killed while running in a blizzard. I wondered was she held captive, having to keep that secret all her life?

No one can possibly judge another's pain, not even a doctor. I found that a very arrogant judgement by the man in a hurry.

Good story!